Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 57, No.2 - Summer 2011

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 57, No.2 - Summer 2011 Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas |

Art as a Witness

Sculptor Mindaugas Navakas

ELONA LUBYTĖ

DR. ELONA LUBYTĖ, Art critic, Curator of Lithuanian contemporary sculpture in the Lithuanian Art Museum, Lecturer at the UNESCO Chair for Culture Management and Culture Policy of Vilnius Academy of Fine Arts, Member of AICA (Lithuanian branch).

Sculptor

Mindaugas Navakas

Navakas’s worldview and motivation are closely related to the popular political activism associated with “1968.” His civic position is one of a critical social activist who rejects any kind of conformity. He was always publicly outspoken, whether playing in Kęstutis Antanėlis’s rock band in Soviet times or voluntarily participating in national security activities during the first years of independence. Speaking against the romanticized relationship between the artist and society, he denounced the unwillingness of the Lithuanian Artists Association to adopt liberal-democratic principles (He quit the association in 1993). He criticized the classical educational approach that Vilnius Art Academy takes with its students.

Navakas’s oeuvre is also marked by a strong-willed consistency. Reflecting the world in aesthetic categories, the sculptor seeks to embody intuitive senses in three-dimensions, to materialize them. This task makes the artist a ruminative technologist, constantly expanding the limits of knowledge, creative decisions, and cultural associations.

Navakas as a sculptor, as an architect of form and space, has always been interested in the postmodern dialogue of cultural meanings and intensely fluid forms that are created between site (public, institutional or alternative) and the associated piece of art (sculpture, object, installation or projection) during the production process. In this dialogue, there lurks a fusion between metaphysical threat, existential anxiety and frivolity, and irony. With each work, while overcoming the creative for himself” (for example, Vilnius Note Book 1 [1981–1985] the ironically postmodern project that proposed Situationist Style habitation, through sculpture, of Soviet-era public spaces).

A closer look at Navakas’s recent work attests to his tireless and consistent vitality as a technologist and researcher. He is loyal to hand-sculpted local granite boulders that he first encountered in 1977, when attending a granite sculpture symposium in Klaipėda. Moreover, Navakas is constantly replenishing his arsenal of expression; he confronts unexpected elements of culture, nature, and industry; he does not succumb to the consumer neurosis of the post-command economy society, and he makes its cult objects, commercial goods, into material for creative remakes.

Equipped with a granite chisel and a diamond-tipped drill that penetrates rock crystal, as well as with a camera and other tools, Navakas remains an “’unclassified’ artist, with a European ‘quality certificate’.1”

Elona Lubytė in Conversation with Mindaugas Navakas2

How does a contemporary artist get involved in the process of change? By choosing the standpoint of romantic distinction or independent survival? As one of the challenges of the new twenty-first century,3 an intellectual worker independent of politics, power and economic crises must organize himself and learn when and how to change. Today, he is mobile and free to choose, since his “production tools” – knowledge and skills – are at his personal disposal. However, changes are still regarded as more like death or taxes: they are considered unwelcome and delayed as long as possible. On the other hand, in periods of upheaval, like the present one, shifts and changes are considered a norm. Certainly, they are painful and risky and require a lot of hard work. In such periods only the leaders survive. Is the struggle with challenges part of an artist’s daily creative process?

Elona Lubytė:

— How does an

artist experience constant changes?

Mindaugas

Navakas:

— It must have been fun to live in the times of Ptolemy. The

earth was flat and stable – the center of the Universe. There

is

a well-known engraving representing a man at the edge of the

Earth, sticking his head through a hole in the vault of heaven

and admiring the constellations passing by. I wonder if he had

made the hole himself or had found it, ready made by someone

else. This question is going to torture me from now on. No

wonder Galileo caused such indignation. It must feel horrible

when you realize that you are jumping on some ball flying at

jet-speed and spinning around its axis. Probably, since then, we

secretly desire to wake up from this nightmare. Another reason

to hate change is the incessant race that goes on in our life. As

soon as we feel that we are losing our strength and someone

else is hot on our heels, we want to shout – stop,

it’s the finish

line! Unfortunately, the race never ends. “Kitty kitty, why

are you shaking, little pussy, you will die!”4 Constant

change

is one of the very few remaining stable things. The best album

by Jimmy Hendrix is titled Them

Changes. In this album, Buddy

Miles, a black drummer of imposing bulk and mass, sings in

a high-pitched tenor the blues number titled

“Changes.” It’s a

shame I haven’t seen it live.

— And how does the constant

process of change influence an artist’s

world outlook?

— I’d prefer that it should happen in the direction

of clarity and

higher precision, but most often, the changes have a frustrating

effect. Rembrandt was not crushed by hardship as an artist, but

he was Rembrandt! Many talented guys were crushed by hardship,

and the names of many others are gone with the wind.

Conformism is not a world outlook. To my mind, creation is an

instinct! The first impulse that gives rise to creation is intuitive.

The ideological motivation and self-control is secondary, but

its presence, the participation of both elements in the creative

process, is desirable.

— Is it possible to trace what

impulse has given rise to an artwork?

Let’s say, the cycle of sculptural objects constructed from

Chinese ceramic

and sanitary delftware displayed at the exhibition?

— Most probably, the impulse was a huge Baroque tile stove

on elegant legs, which I saw standing in the center of a room

at Kadriorg Palace in Tallinn in 1973 or 1975. Empress Catherine

once used to warm herself by this stove. However, you

can never tell with this impulse. Every day your gaze flashes

by a thousand shapes appearing in the visible field, but gets

captured by very few. The point is why it gets captured.

— Can you explain why, from among

thousands of goods on the supermarket

shelves, your gaze was captured by these particular objects

referring to globalization and consumer society?

— A supermarket shelf comes by accident, because, as I

already

mentioned, I got “captured.” All these objects have

been remade,

and most of them have been put through a new technological

cycle – fired, glazed. They are raw material rather than

an object with independent meaning. This process can be compared

with the production of sculpture from sheet metal. Sheet

metal is not found in nature; it is iron ore that is mined.

— Is this “getting

captured” constant or changeable?

— For some time now, I have been trying to use the

possibilities

offered to me by the context (circumstances). It means that,

quite often, I must alter my preconceptions and sometimes

even start everything anew. What is important in this exhibition

is the space densely filled with information, the hall lavishly

decorated in the Eclectic Style rather than the institution

itself. I try to develop a side story referring to the topic offered

by the site.

— What is more important, the

process of remaking or a remade object?

Let’s say, the installation with the old truck tent

– why has it been

chosen from a thousand objects? It is a kind of neo-brutal reference to

the infinite horizons of the world that have opened before us, general

transit, migration and lack of security changing the romantic attitude

toward travel experience.

— I can only say that I liked it. It is flexible, firm and

windresistant.

I’m not so keen to find out why. It is enough that I

got captured by it and, having chosen it as raw material,

started

remaking it.

— Let’s return to the

question about an artist’s stance in the environment

of challenges and changes: does he adapt himself, does he try not

to notice them, or does he try to become a leader?

— The answer is related to world outlooks. In my opinion, in

the universal court, process art is a witness rather than a judge.

A fragmented, changing and moving reality is a live and vital

reality. What is stable may be stagnant, frozen, and dead. The

social reality of parliamentary democracy is an arguing, quarrelling,

constantly negotiating and renegotiating, dynamically

developing reality. But I’m not interested in social issues

in my

art practice. I find artists who analyze social topics naïve,

since

they imagine that they can change the world. The twentieth

century abounds in examples of the naïve engagement of artists

in social life, which ended badly, either for the artists, or for

society, or both.

— What is the world outlook of an

artist who is not naïve?

— An artist who is not naïve is a Stoic, from the

viewpoint of

the ancient Greek tradition.

— And how is it expressed today?

— It is expressed in persistence in doing your work, without

regard to unfavorable circumstances. An artist’s aim is to

reflect

on the world in aesthetic categories. Unlike applied art,

fine art does not aim to satisfy the client’s tastes. The

question

is one of totally different aims, in the presence of which art becomes

a struggle for survival.

— Can we regard this attitude as a

small personal challenge to the

environment?

— A challenge is something that requires putting forth more

effort than usual, facing an obstacle larger than usual. Artistic

creation, as I have mentioned, is an instinct, and this often

helps to conquer obstacles larger than usual.

— If an artist seeking to solve

social issues is naïve, then what issues

should be solved by an artist who is not naïve?

— Personal issues, but in terms of subconsciousness rather

than on a biographical level. Personal experience is a kind of

pool ball that hits other balls in a state of equilibrium. A

pinch of fun is very important to me. I wouldn’t

like to educate or

convince anybody.

— Should it be related to the

restless/fidgety nature of an artist?

— The category of anxiety is crucial here. Anxiety is always

present. It is hardly related to exterior changes or an unstable

environment, it is deep, existential. It is an important impulse,

an engine in action, a constant escort. I came to the conclusion

that creation is little related to the artist’s peace of

mind. Perhaps

it is the curse of the artist – you are doomed to be in an

intermediate state, because if you leave this state, you may lose

your creative impulse. But then, the world would be a bit more

boring.

— However, doesn’t an

artist conveying personal experience in his

work also reflect some generally urgent issues?

— I think it is a romantic utopia. As I said, art is a

witness rather

than a judge. It is nice to observe it in the past tense, and

that’s

what museums are for.

Translated by Aušra Simanavičiūtė

*

* *

MINDAUGAS NAVAKAS was born on January 24, 1952 in Kaunas and now works in Vilnius. In 1970-77 he studied Architecture and Sculpture at the State Institute of Art of the Lithuanian SSR, and taught sculpture there from 1977 to 1981. Since 1990 he has taught at the Sculpture Department of the Vilnius Academy of Fine Arts. Navakas has been holding exhibitions in Lithuania and abroad since 1977, including at the first Lithuanian National Pavilion at the 48th Venice Biennial in 1999.

Navakas has participated in numerous symposia in Lithuania, Germany, Finland, Korea, and Latvia, organized sculpture exhibitions in public spaces, and created site-specific works such as The Hook at the Art League, Vilnius, 1994; Reconnaissance in Helersdorf, Berlin, 1997–1998; Big Fish in Tranoy/Hammaroy, Norway, 2006; and others. His awards include the Herder Prize in 1995, the National Prize for Culture and Art of the Republic of Lithuania in 1999, and the Baltic Assembly Prize in 2004.

* * *

Notes:

1 Giedrė Jankevičiūtė, “An ‘Unclassfied’

Artist with a European ‘Quality

Certificate’,” in Kultūros barai,

2000, No. 1, p. 18.

2 “Art as a Witness: An Interview with Mindaugas Navakas, by

Elona Lubytė,” in Interviu,

2006, No. 5, 12–13, 41–40.

3 Peter F. Drucker. Management

Challenges for the 21st Century. Butterworth-Heinemann,

paperback edition, 2002.

4 Kostas Kubilinskas (1923-1962), Lithuanian lyrical poet who mainly

wrote for children.

Mindaugas Navakas. Grand

Vase, 2005.

Polished and chiselled granite, 450 cm x 250 cm x 200 cm.

“R Works,” Latvian National Museum of Art, Riga,

2006.

Photo by Arūnas Baltėnas

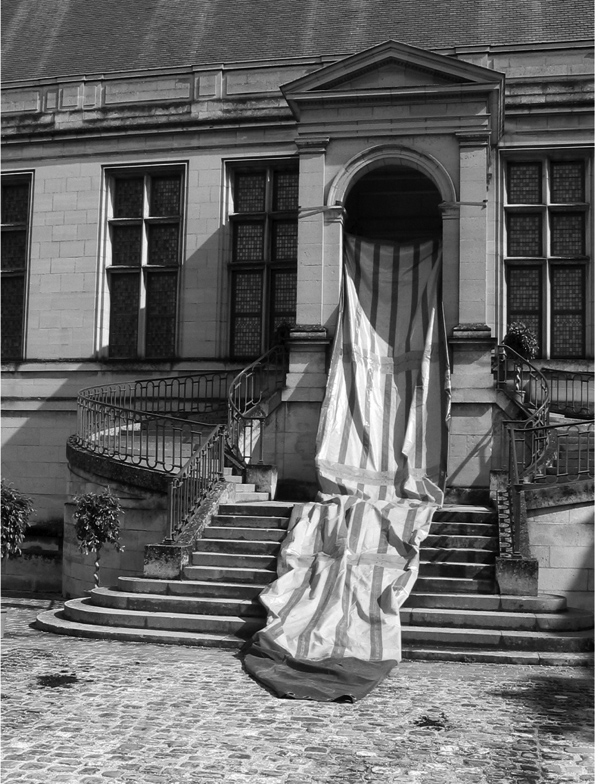

Photos by Mindaugas Navakas:

Folded V.

Used truck canopy (polyvinyl acetate/polyester), webbing belts, rope

1600.

Show “Ex voto,” Reims Palais du

Tau, Reims, France, 2008.

Red. Polished and split granite, 520 cm x 120 cm x 70 cm, 2004.

Personal show, R–O Works, Contemporary Sculpture Museum, Oronsk,

Poland, 2006.

Smash the Windows, Snatch the Crystals, 2009.

Old CAC windows aluminumnprofiles, glass, rock crystals, 570 cm x 310 cm x310 cm.

“Frieze Art Fair 2009,” London.