Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 57, No.3 - Fall 2011

Editor of this issue: M. G. Slavenas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 57, No.3 - Fall 2011 Editor of this issue: M. G. Slavenas |

IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE GULAG

TOMAS KAZULĖNAS

TOMAS KAZULĖNAS is a graduate student at Vilnius University majoring in cultural heritage preservation. He is also associated with the Center for Genocide Research in Vilnius.

Abstract

This is a personal account of the 2009 expedition sponsored by the

Association Lemtis to Vorkuta, Abez, Inta, Pechora, Kortkeros and

Syktyvkar in the Komi Republic in order to document cemeteries

and gravesites and repair and restore memorials erected after 1990 by

volunteers in honor of the Lithuanian prisoners and deportees buried

there during the Soviet era. Vorkuta was the largest of the Gulag

camps and served as the administrative center for smaller camps

and subcamps. The name Vorkuta has become a metaphor for the

Gulag, a place of evil built on human skulls and mass graves. Lithuania

built more symbolic memorials and tombstones for their dead

than any other country. By the late fifties, after Stalin’s

death, Vorkuta

was closed down. (For information on the Vorkuta Uprising see L.

Latkovski, “Part

I.

Baltic Prisoners in the Gulag Revolts of 1953”

in Lituanus

Vol.51:3 and "Part II. Baltic Prisoners in the Gulag

Revolts of

1953" Vol.

51:4, 2005).

Introduction

|

| Tomas Kazulėnas, author of this article |

|

| Gintautas Alekna, guide of the expedition |

The history of deportations and imprisonment – with the suffering caused by the hardest slave labor, homesickness, exhaustion, starvation, and death – is slowly fading into oblivion. The future, however, is built on the foundation of the past, and the association Lemtis (Destiny) has made it its mission to preserve Lithuania’s historical heritage for the future and to honor those who suffered and succumbed in Siberian camps during the Soviet occupation. Cooperating with other educational institutions sponsoring similar projects, Lemtis has recently celebrated its twentieth anniversary. During this period, the association has organized more than twenty expeditions to numerous labor camps in Siberia that held prisoners from Lithuania. Association members also participated in eight additional expeditions. Travel in Siberia and other Russian regions – by plane, train, automobile, all-terrain vehicles or on foot – covered more than 350,000 kilometers. More than 500 deportation locations and 350 cemeteries and gravesites were visited and documented.

❖ ❖ ❖

The 2009 expedition took place from August 31 to September 13. Its leader was Gintautas Alekna, an experienced guide, photographer and cinematographer, who had organized previous expeditions to prison and exile sites in Siberia. This was his twenty-ninth trip. Other members were Gražina Žukauskienė, on her tenth expedition; Tadas Kvasilius, a graduate student of history at Vytautas Magnus University on his third trip; Artūras Kvasilius on his first expedition; and this writer, Tomas Kazulėnas, a graduate student majoring in cultural heritage preservation at Vilnius University, on his third trip. This time we traveled to the Komi Republic and visited cemeteries in the areas of Vorkuta, Abez, Inta, Pechora, Kortkeros and Syktyvkar, cleaning them up and repairing and restoring memorials erected after the reestablishment of Lithuania’s independence by volunteers to honor Lithuanian prisoners and deportees buried there during the Soviet era. We also visited several Lithuanians residing in the area and met with members of the Russian Memorial Association, a Russian human rights organization that is dedicated to recording and publicizing human rights violations.

Vorkuta was the largest center of the Gulag camps in the European part of the USSR and served as administrative center for a large number of smaller camps and subcamps, among them Kotlas, Pechora, and Izhma (modern Sosnogorsk). Many Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians were imprisoned throughout this vast expanse of the Gulag, with a heavy concentration of them across the northern part of European Russia, including the Komi Republic prison camps of Kotlas, Ukhta, Inta and Pechora that surround Vorkuta. Entire families were brought here during the first deportation in 1941 or later and forced to work in timbering and railroad construction. Other Baltic nationals were deported to the Ust-Ukhta group near Vorkuta, with about thirty camps, and the Ust-Vym complex of twentytwo stations on the Vologda-Kotlas-Ukhta railroad line. In 1941, the prisoner-built railroad connected the town and the labor camp system around it to the rest of the world by linking Konosha and Kotlas, and the camps of Inta.

Although much on this subject has been written, researched and analyzed, one feels upon arrival in Russia that there is a tendency to minimize or totally ignore the history of the Gulag. It seemed to us that a deeper understanding and critical evaluation of the past was lacking among the local population. On the other hand, many people we met were unwilling to talk and appeared fearful and insecure, apparently still shackled by a fear that should have disappeared by now as a mechanism of control, but has not. It seems too difficult for them to break free. Deeply embedded in the mindset and actions of this society is a lack of initiative and confidence along with feelings of helplessness and passivity, a mentality which had been fostered by the Soviet government. The system had robbed its people of its best characteristics.

Vorkuta – Tragic Past and Dismal Present

Vorkuta is situated in the Komi Republic of the Russian Federation, to the west of the Ural Mountains, in the northeastern region of the European part of Russia, 110 kilometers north of the polar circle, 1,200 km from Moscow, in one of the least hospitable environments on earth – deep within the Arctic Circle. Most of the territory is covered by dense forests and mosquito- infested swamps. In the 1930s huge coal reserves were discovered in the area of Vorkuta and prisoners were shipped by the hundreds of thousands to perform slave labor in this Arctic region of the USS R under unimaginably harsh conditions. The trains that brought prisoners to Vorkuta returned filled with coal. The labor-camp sites were initially carved out of the untouched tundra and taiga by the prisoners themselves, and later towns sprang up around them. Vorkuta was an important transit station in the Gulag Archipelago. It served as an administrative center for a large number of smaller camps and approximately 132 subcamps, among them Kotlas, Pechora, and Izhma.

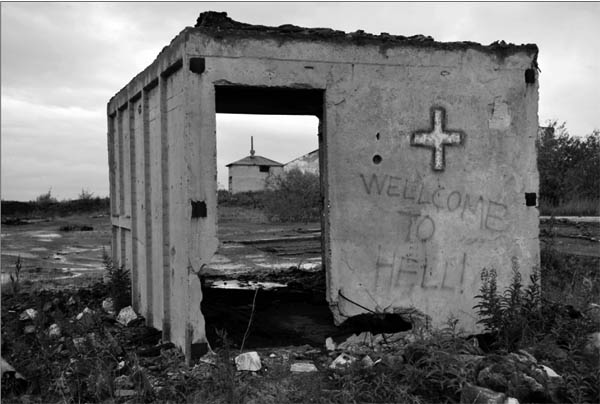

Vorkuta is the largest of the camps. The name is familiar to many throughout the world. It is associated with prisons, slave labor camps, crippling work in the coal pits, unbearable suffering, degradation, brutality, starvation and death. Lives of survivors were damaged beyond repair. Historians say that, out of more than two million deportees between 1932 and 1954, about 20,000 or more prisoners (known as zeks) had perished in the camps around Vorkuta of maltreatment or malnutrition, and approximately one million were executed. The exact number will probably never be known. The name has become a metaphor for the Gulag, a place of evil built on human skulls and mass graves.

The deportees and political prisoners from the Baltic States would reach their destination in about a month. They were transported in cattle cars without the most basic comfort, under unsanitary conditions with starvation rations of food and water. They were labeled enemies of the people and mistreated by the guards. Many of them perished during the journey. To the prisoners, the train tracks were like gates to hell from which few returned.

|

| Tundra |

The railroad system in Russia works well and railroads are the main mode of transportation, but this two-day trip made us feel that Vorkuta is very far from other centers of civilization. It is surrounded by coal mines and pits built by the bare hands of prisoners. The primitive camps were also built by the prisoners themselves. There are no towns in the vicinity, only swamps and rivers. The tundra reigns supreme. It stretches as far as the eye can see. The climate is harsh. During the eight-month polar night, the wind howls and the temperature plunges to minus fifty degrees Celsius. During the few short summer months the sun is not able to penetrate the ground which remains eternal ice. In summer, the air is filled with dense clouds of mosquitoes and tiny black flies. Geography and the harsh climate made it an ideal place for prisons and slave labor. Escape was impossible.

Our train trip from Moscow to Vorkuta lasted two days. We noticed how far we had traveled by the changing time zones, the changing landscape and changing temperatures. We left Vilnius on the last day of summer: the sun was shining, the thermometer read twenty degrees Celsius. As we approached the polar circle, the landscape turned to autumn and eventually to wet snow. Indeed, we were going north, to where the earth ends and the vast Arctic Ocean begins.

The grandfather of one member of our expedition was imprisoned in Vorkuta, where he did the backbreaking work Vorkuta is known for. Now we were walking in his footsteps. The difference was that we had come here voluntarily. We were trying to understand and visualize the life of the prisoners, but we were only visitors. Can we ever fully understand what they experienced? Their homesickness, the craving for minimal comforts, a normal meal, a good night’s sleep, soap and a shower, for a warm room? Where did they find the strength to retain human dignity in the face of so much cruelty and injustice?

Under Nikita Krushchev, after Stalin’s death, steps were taken to begin the destruction of the Gulag system. The poorly built camps were torn down and burned, or they were scavenged by poor peasants in the area. Work in the mines continued, but for pay. Most of the prisoners moved away, but not all were permitted to leave. There were also those who remained of their own free will. Among them were many deportees and prisoners from Lithuania who stayed on in this town north of the polar circle because they had nowhere else to go, or because they were not welcome back home, or because their spirits had been broken.

|

| Cemetery in the tundra |

Life in Vorkuta is bleak. Not that long ago, for about several decades, it had a population of 240,000, but now, this number has shrunk by about half, and only half of those lead productive lives. In the evening, we met Mr. Kalmykov, the chairman of Vorkuta’s Memorial Association, who told us many interesting facts about Vorkuta’s past and its residents. We found out that the city sits on layers of coal about one kilometer thick and that there was enough coal to provide work for the next two hundred years. Today, however, almost all of the former coal mines are closed and the city is dying.

According to Memorial’s estimates, of the approximately forty thousand people collecting state pensions in the Vorkuta area, thirty-two thousand are trapped former Gulag inmates or their descendants. With such a large percentage of the population unemployed or surviving on government pensions or subsidies, there is no life there now, only ghosts of former lives. The city is visibly shrinking and in the process of disappearing altogether. Does it have a future? It could become a tourist destination with a historical research center. But history is consciously and deliberately destroyed here. It lingers in people’s memories, but for how long? Some of the old folks we met remember the horrible past all too well, but they refuse to rummage through the ashes of history.

When we arrived, it was just the beginning of September, but the weather had already turned against us. It poured steadily for three days. On the first day, we visited the principal coal mine, also known as Kapitalnaya, but almost everything there had been demolished, removed or leveled. We saw only the remnants of barracks surrounded by strands of barbed wire and a partially destroyed monument dedicated to this coal mine. Five years ago, we were told, there was still a central building on this location, serving as a reminder of the past, but it had since been destroyed. It is doubtful that former prisoners would be able to recognize this place which had left so many wounds and scars on their hearts and robbed them of the best years of their lives.

The original inhabitants of this area are the Komi people. Over one million people live in the present Komi Republic, representing more than seventy different ethnic groups. Russians comprise the largest population group (58%), followed by the indigenous Komi (23%), who have an ancient culture and a language that belongs to the Finno-Ugric group of languages. The official languages in the republic are Komi and Russian. The Komi were once great warriors. They are now known as an industrious and honest people, generally engaged in cattle breeding, hunting, and woodworking. Waterways were their main means of transportation and communication. Since the fourteenth century, the Komi territories have been incorporated into the Russian state and the Russian Orthodox Church. For several centuries, the Komi were divided and fought against each other, thus gradually destroying their ethnic identity and the will for statehood. With Russian settlers colonizing their lands, the Komi lost much of their own customs and culture. Russian replaced the Komi native language, which is written in the Cyrillic alphabet. Today it is difficult to tell the difference between the Komi and their Russian neighbors. Yet the spirit of the Komi people is still alive and efforts are made to foster their history and traditions.

Silent Witnesses to the Past

We visited the former Yur-Shor settlement which is not far from Vorkuta. By the cemetery of the Twenty-ninth Mine is a large monument, the largest of all memorials erected in memory of Lithuanian prisoners who perished here. It was designed by the Lithuanian sculptor Vladas Vildžiūnas and the architects Rimantas Dičius (Lithuania), Vitalij Troshin (Russia), and Vasilij Barmin (Russia). This monument has by now become a symbol for all Vorkuta prisoners. Here also are buried the participants of the famous Vorkuta Uprising.

|

| Memorial

for Lithuanian prisoners in

Yur-Shor near Vorkuta. Sculpture of Christ (1990) by Vladas Vildžiūnas. Monument design by architects Rimantas Dičius, Vitalij Troshin and Vasilij Barmin, 2009. |

This memorial consists of huge granite blocks, two-anda- half meters high. On top of the blocks stands a three-meterhigh bronze sculpture of Christ. It is surrounded by several meters of high iron columns, joined by open arcs. Against the backdrop of the endless tundra, with its palpable sensation of vast space, it leaves an indelible impression. We felt all alone and forlorn in this immense land.

Compared to other countries, Lithuania built more symbolic memorials and tombstones for their dead than anyone else. Most were built in the 1990s, soon after the reestablishment of independence, when the preservation of the historic past was of special significance and fostered national awareness and unity.

Two kilometers from the cemetery, we found the location of the famous Vorkuta Uprising, perhaps the only one in Gulag history. It housed a majority of political prisoners, including many from the borderlands and western areas which had resisted a Soviet takeover. During the first days of August 1953, the workers organized a protest against the unbearable working conditions and inhumane treatment by guards and went on strike with the slogan “No bread – no coal.” With the rebellion spreading, army units were called in and the uprising quelled by gunfire. About sixty prisoners were killed, among them eleven Lithuanians. About three times as many were wounded and left unattended and without medical help. The strike was somewhat successful in improving the conditions. By the late fifties Vorkuta was closed down.

Today, this tragic area is also overgrown with grass and brush. Most of the signs that bore witness to its horrible past have been obliterated. We recognized it only by the barbed wire – the only clue left to judge the dimensions of the camps. Reinforced concrete posts were holding the barbed wire, bits of concrete pavement, and overgrown paths were still visible in some places. Everything is sinking into the tundra, doomed to decay and decomposition, as the government intended.

On our way back, we stopped at the international cemetery at Severnyj. At the entrance rises an impressive fairly new monument to Hungarian prisoners. We again found several Lithuanian markers. Although it was already September, we were still under constant attack by the tiny black flies that all prisoners remember as a scourge. Their bites left red itchy marks all over our bodies. It was impossible to evade them.

We also passed the Fortieth Mine, called Vorkutinskaya, which is still operating, producing about eight hundred tons of coal every twenty-four hours. On the other side of the road rose a monument built by Poles. These crosses scattered throughout this vast area reminded us that we were walking on an endless killing field. But among the local population, we found no support for our expedition, or interest in it.

|

| Vorkuta, 2009 |

We stayed in Vorkuta for three days and the rain never stopped. Although we were prepared for bad weather, this relentless downpour was very disabling. Nevertheless, we continued with our exploration as best we could. We found one more graveyard in a somewhat secluded tundra region near an extremely tall metal cross that was visible for several kilometers. Its top, rising high above the horizon, showed us the way like a guiding star. It was a memorial cross to Ukrainian victims. The graves were already overgrown. Only the wooden crosses were still trying to reach the sunlight, to be visible and to bear witness to the past. We again found Lithuanian names. It was a very strange sensation to look at them in the middle of the tundra so far from their homeland. It seemed somehow intimate and familiar.

When the sun finally appeared, the city, which had seemed hopelessly dismal, dirty, and gray, lit up and became much more inviting. We took a walk along the central street, which is still called Lenin Street. Many streets here have retained their Soviet names. Lenin Street is different from the others: it is broad and wide, obviously built for parades. We also encountered Stalinist-style buildings with bombastic slogans such as Vorkuta, the strong hands of the miners protect you; Vorkuta celebrates the Day of the Miner. We visited the central post office to buy a few postcards. The confused reaction of the postal clerk demonstrated that in this city foreign visitors were rare, and no one was interested in souvenirs. Nevertheless, after some hesitation, she disappeared for about ten minutes and returned with a few thin packages of dust-covered postcards. The date on the back was 1992! It is difficult to describe their substandard quality when compared to the shining western postcards that we are used to. They were quaint antiques finally having found a buyer after seventeen years.

Early the next morning we took the bus to the cemetery in Oktiyabirsk. There all markers bore the same date of death: 1964. Unexpectedly we came across a fairly new man-sized oak cross with a Lithuanian inscription: “To the memory of Lithuanian deportees.” It was dated September 5, three years before. By a strange coincidence, exactly three years before, another group of Lithuanians had been in this very place! When we returned to the bus, a few local passengers stared at our video equipment and asked: “Are you from Hollywood?”

Abez – Settlement on the Arctic Circle

After a week in the inhospitable lands of Vorkuta, we left this most northern point of our expedition by train before five o’clock in the morning. Our new destination was Abez settlement, situated on maps on the line shown as the Arctic Circle, once had the status of a major city. It was an important site when the railroad line to Vorkuta was being built. There had been seven prison camps around Abez with approximately twenty thousand inmates who laid the railroad tracks through the swamps with their bare hands and built a large bridge across the Usa River. On the train, every seat was taken by locals on their way to pick mushrooms or berries in the surrounding forests. They were lugging homemade boxes and huge baskets and reminded us of photos of Vietnamese peasants taken during the Vietnam War.

In the middle of the last century, about thirty thousand people lived in Abez. Here too, with the dismantling of the camps, residents left the area. Now only seven hundred remain. There is a school in Abez with eighty-three students. The school janitor, Vasilii, with a powerful smell of liquor on his breath, kept pointing to a poster of Dmitrii Medvedev and tried to convince us that the Baltic nations were Russia’s enemies. We did not respond. It is useless to argue with a drunk.

|

| Abez Memorial Cemetery |

In Abez, as everywhere else, we were warmly met by volunteers at the local Memorial Chapter. Mr. Lozkin, the chairman, was a calm person and a dedicated researcher of history. We visited and tidied up the Memorial Cemetery marked by an impressive monument called “The Flaming Cross” (Liepsnojantis kryžius), erected in 1992, dedicated in four languages “to those who did not return.” About 150 Lithuanians are buried in the cemetery at Abez. Among them are the remains of Levas Karsavinas, a professor and famous philosopher and art historian who lived in Lithuania from 1928 to 1949. His grave is marked as Number 11. Not far from his grave is buried another famous Lithuanian, General Jonas Juodišius. We cleaned up their gravesites, cut down some branches and bushes, lit a candle and paid our respects in silence. This cemetery has been granted the status of a Memorial Cemetery, but everything is neglected and a part of it is already gone.

In Abez, we went shopping for a few items. New shipments arrive sporadically because the only means of transportation is the railroad. The town has three stores, all of them privatized. One was still government-owned, but it recently burned down. Shopping in Russia is always an adventure. In the store, the choice of goods was very limited by our standards, yet the young sales woman was trying to convince us that she had plenty of everything. In general, we found that the locals in Abez were also avoiding contact and conversation with foreigners. People were obviously still in the grip of the fear that had controlled their lives for fifty years. The only pleasant sight in this gloomy place was the river Usa, with unharnessed horses peacefully grazing on its banks, creating a quiet, tranquil, unspoiled atmosphere.

The Paradox of Inta

After Vorkuta, the densest network of labor camps and coal mines was located in Inta. This city, like many other cities in this area, was also built by prisoners. Several thousand Lithuanians were imprisoned here. Fifteen years ago, the city had seventy thousand inhabitants, but this number has since shrunk to about forty thousand.

The train trip to Inta lasted almost twenty-four hours, and little did we know that we would spend another twenty-four wakeful hours after getting there. When the train stopped in Inta after midnight, we learned that the town was still about seven kilometers away. The bus did not run at that time. Locals used various means to get there – some hitchhiked and risked getting a ride in cars aggressively driven by young men, others simply walked. We decided to take the risk and hire a cab, which took our entire group to a hotel in town. We could barely wait to get to our rooms and get some sleep, but the manager took one look at our foreign passports and quoted a price that we were not able to pay. No pleading on our part changed his mind. We had no choice but start the new day without a rest.

In Inta, we visited the Memorial Cemetery Vostochnyi, where Lithuanians and Latvians had erected their crosses. Sixty Lithuanians are buried here. The Latvian cross is unique because it was erected in 1956, the first attempt in the entire Soviet Union to memorialize and honor the victims of political repression.

When we arrived at the cemetery, we were surprised to find a group of students there from a neighboring school. We had a pleasant chat with the teacher who told us that there was another camp close by (Russians call these camps lager). The teacher insisted that we come to her school, visit the school museum, and meet the principal. It turned out that the principal’s father was Lithuanian. The mayor’s wife was also Lithuanian! The friendly welcome we received from them cheered us up and made us for a while forget the sleepless night we had to endure because of the city’s inability or unwillingness to accommodate foreign tourists.

While waiting for the bus to take us back to the railroad station, we met two nice little girls who obviously lived in extreme poverty. One wore torn shoes, the other had a threadbare backpack on her shoulder. Yet they were chatty and unafraid to carry on a conversation with us. They wanted to know where we came from and begged us to take them with us. There was nothing we could do for them except trying to cheer them up with a few pretty pictures from Lithuania. For a long time we saw them through the windows of the bus waving to us.

In Pechora, which we reached by train, we discovered, in the middle of the town, the administration center of the former camp. The remains of the camp were still visible: rows of barbed wire, guard towers and collapsing barracks. We were not able to get information about Lithuanians living there.

Visiting Lithuanian Settlers

We traveled another night by train to Syktyvkar, the capital of the Komi Republic, and from there to the town of Kortkeros, the next destination on our itinerary. Our goal was to visit several Lithuanians. One of them was Irena Šeškūnaitė. She was in poor health and had already forgotten how to speak Lithuanian. Her family history is tragic. She was deported from the town of Šiluva as a child, together with her parents, grandmother and brother. Her father was shot dead in one of the railroad stations along the way. They endured extreme hunger, and her grandmother starved to death. On the collective farm, her mother tried to steal a bucket of potatoes from the general store and was sent to prison. Irena and her brother were placed in a children’s home, where they grew up. After having served their time, they managed to reach Lithuania, but their relatives were so unwelcoming that they had no choice but to return to Russia. There, Irena met and married Aleksas Mingėla, a Lithuanian from the village of Barstytis, in the Seda region, whose family had also been deported in 1941.

|

|

Members

of Lemtis with

Anatolijus Smilingis (second from the right)

and his

wife in Kortkeros, Komi Republic

|

In Kortkeros we met Anatolijus Smilingis, who is wellknown among the locals for actively and energetically organizing the building of memorials for the Gulag victims. He works at the local Center of Culture and organizes trips to the ethnographic museum, which he himself established. His wife is a Komi. She is involved in preserving her own nation’s customs and cultural heritage.

Anatolijus, together with his parents and sister, was also deported in 1941. His father was separated from them and sent to a labor camp in the Krasnoyarsk region, where he was executed in 1942. Anatolijus worked with his mother and sister in the forests cutting trees for lumber. They were starving, and his mother too was convicted for theft and sent to prison for stealing a few handfuls of oats. She died half a year later, leaving him and his sister orphaned.

We next looked up Vaclovas Zubis, whom we found working in his garden. He looked happily surprised to hear a Lithuanian greeting but had difficulty expressing himself in his mother tongue. Vaclovas and his parents were deported from Vėžaičiai in the Klaipėda region in 1941. He too had married a Komi and had three children. Vaclovas told us that he was the founder of the local hunters club and that the surrounding forests housed a wide variety of bears.

Vaclovas took us to see Genutė Rekošaitė (Golysheva), who met us at the entrance to her home. Upon hearing our greetings, she began to cry and made no attempt to hide her nostalgia. She had not spoken Lithuanian since 1982, but was still fluent in the language and used many authentic expressions that had been current in her time. Her life history paralleled that of thousands of others who had remained in Siberia or some other place where they had been exiled or imprisoned. Genutė and her family came from the village of Žaiginiai in the Raseiniai region and, after her parents died, she married a Komi. Like so many others, Genutė had to work in the forests cutting down trees. Later, she was assigned to mowing hay. She told us that there had been another cemetery in Ust-Lokchim, which had since decayed. Out of some four to five hundred Lithuanians who had lived in Ust-Lokchim, about sixty were buried in the old cemetery. Later, a road was built through it and garden plots established.

|

| Members of Lemtis by a monument in Ezhva |

The last monument we saw was in Ezhva. This too bore an inscription in several languages and was dedicated to the deportees of 1941. The surrounding air was heavy with a dense, pungent odor from a nearby celluloid plant; the plant was built by prisoners.

We spent the last day before our two-day train journey back home in Syktyvkar, the capital city of Komi. We were invited to the local TV station to talk about our expedition. The program director was very interested in our work, asked many questions, and wanted to show the entire interview on the main channel.

As we look back on our expedition filled with unforgettable sights and memories, we are aware that the graveyards we visited will not last forever. Thousands of innocent victims lie buried, and they should never be forgotten. It will be up to us to keep their memory alive.*

Translated by Daiva Barzdukas

* An earlier version and articles by other authors on other expeditions are available at www.lemtissibiras.lt