Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 57, No.3 - Fall 2011

Editor of this issue: M. G. Slavenas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 57, No.3 - Fall 2011 Editor of this issue: M. G. Slavenas |

The Classical Sculpture of Vitolis Dragunevičius (1927-2009)

STASYS GOŠTAUTAS

Abstract

A review of the life and work of Vitolis Dragunevičius (1927-2009),

another graduate of the Freiburg art school École des Arts

et Métiers,

founded and directed by Vytautas K. Jonynas. During its five-year

history (1946-1950), the school produced an entire new generation

of émigré artists.

Most of us are familiar with many of the names of the generation of sculptors, painters, and ceramists from the École des Arts et Métiers in Freiburg who emigrated to the USA and contributed their art to the Lithuanian and American communities here. Their talent and training greatly influenced post-World War II Lithuanian émigré art. Of the 129 students from the Freiburg group, eight have died in the course of the last decade, starting with Elena Urbaitytė-Urbaitis (1922-2006), Albinas Elskus (1926-2007), Sandra Laucevičiūtė-Čipkuvienė (1922–2009), Vytautas Ignas (1924-2009), Juozas Mieliulis (1919-2009), Vitolis Juozas Dragunevičius (1927-2009), Janina Monkutė-Marks (1923-2010) and Ramojus Mozoliauskas (1925-2010).

Sculpture Students of

The École des Arts et Métiers around 1947. From

left to right:

Vitolis Dragunevičius,

Juozas Pivoriūnas, Ramojus Mozoliauskas, Antanas Mončys ir Vladas

Petryla.

The École des Arts et Métiers was founded and directed in post-World War II Germany by Vytautas K. Jonynas in Freiburg, under the French flag, in the French Zone of West Germany. The professors were established Lithuanian masters, such as Viktoras Vizgirda, Algirdas Krivickas, Adomas Galdikas, Adolfas Valeška and others, all of them refugees from Lithuania who found themselves in Displaced Persons camps in war-torn Germany. In this school, an entire new generation of Lithuanian artists was born. More information about this unique school that lasted only five years, from 1946 to 1950, can be found in an art catalogue compiled by Victoria Kašuba– Matranga and published in the 1980s.*

* Catalogue for “Refugee Artists in Germany, 1945-50. Lithuanian Artists at the Freiburg École des Arts et Métiers,” University of Illinois at Chicago, May 18-June 8, 1984 and Čiurlionis Art Gallery on January 18-27, 1985.

Vitolis Dragunevičius, gifted sculptor and figurative draftsman, made his living in the United States as a designer and fabricator of religious monuments and statues and spent all of his creative life striving for artistic perfection. Commercial art kept him from doing what he would visualize, because religious sculptures and cemetery monuments had to be done according to standard rules and the specific desires of his clients, and there was not much room left for artistic freedom. Vitolis demanded more of himself than the Florentine masters he admired.

|

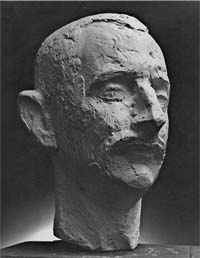

| Vytautas Ignas, plaster sculpture, ALKA Archive in Putnam, Connecticut. |

Vitolis was born in Utena, Lithuania, in 1927. When he was seventeen years old, he found himself with other refugees from Lithuania in a Displaced Persons camp in Hanau, West Germany, and two years later moved to the French Zone to enroll in the École in Freiburg. He had received a box of oil paints from the United States and was eager to study painting, but since the painting classes were filled he was offered the opportunity to study sculpture instead. He gave his treasured paint set, with some regret, to Vytautas Ignas–Ignatavičius, with whom he remained a lifelong friend. A portrait bust of Ignas made by Vitolis can be found today at the ALKA Archives and Museum in Putnam, Connecticut.

At the Freiburg École, his teachers were Aleksandras Marčiulionis and Teisutis Zikaras. His colleagues were Antanas Mončys, Vytautas Raulinaits, Balys Grebliūnas, Juozas Pivoriūnas, Ramojus Mozoliauskas, and Vladas Petryla, who, thanks to Marčiulionis’s pedagogical talents, enlivened the panorama of the émigré sculptors in this country.

Vitolis won a scholarship to continue his studies with Antanas Mončys in Paris, but the arrival of a US visa changed his plans, and he left for Hartford, Connecticut, to join his parents. After two years in the US Army, he continued his studies at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where sculpture was taught by Hubert Yencesse – the well-known designer of Olympic medals. Since the army would not pay for his studies there, he used his own savings and temporarily stayed with Vytautas Kasiulis, his drawing-design teacher from his Freiburg days. On January 18, 1954, he wrote to his future wife Gražina Krasauskaitė, herself a graduate of the Hartford Art School: “Today was the opening of Kasiulis’s art show with hors d’oeuvres and champagne. It is his tenth show in Paris. Too bad, the gallery was too small and could not hold more than sixteen paintings. The pictures were interesting thematically, unique, colorful, and as you have noticed, elegant. It is pleasant to see a Lithuanian artist represent himself so well in Paris.” On June 12, 1954, he writes about Arbit Blatas: “He is from Lithuania. His paintings are colorful, with strong interesting themes.” (Blatas’s widow Regina Resnick, a mezzosoprano at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, donated 340 of his works to the Lithuanian Art Museum).

After finishing his studies in Paris in 1954, he spent several months traveling to Rome, Milan, Venice, and Florence, where he learned to admire Michelangelo and Donatello. His studies in Paris and travels through Italy matured him as an artist. He returned to the United States on the Andrea Doria, which, incidentally, sank only a year later near Nantucket, Massachusetts. Many interesting letters to his future wife survive from his stay in Paris and his trips to Italy.

While in Paris, Vitolis spent a great deal of time at the Louvre with a sketch book in hand. He was charmed by the miniature Greek sculptures, their graceful poses and perfection of form. Since his days in Freiburg, he had greatly admired the two great French sculptors of his day, Aristide Maillol (1861- 1944) and Charles Despiau (1874-1946), Rodin’s assistant. His favorite was Maillol. Vitolis’s widow remembers that, whenever he visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he always stopped to reconnect with Despiau’s portrait of the Madonna and never tired of explaining the subtleties of line and the beauty of form in the portrait.

|

|

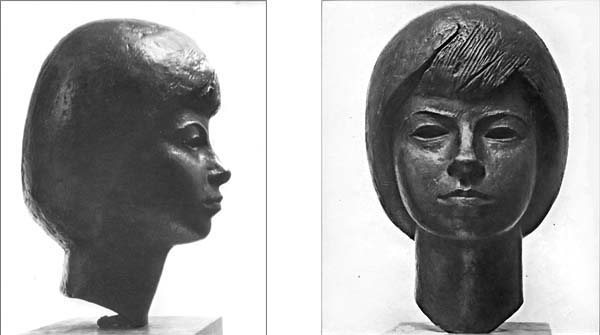

Nijolė

Ulėnienė, bronze, 1963.

Photo

by V. Maželis |

Neither time nor hard work tired Vitolis. In 1957, he and his wife Gražina moved to Barre, Vermont, to join a company called Rock of Ages Monuments, where he learned to work in hard granite, a skill necessary for monument production. For fifty years he maintained studios in the Bronx and Westchester County, New York. He made bronze portraits of V. Valiūnas and his sons, V. Vebeliūnas, B. Rauckienė, A. Pakštienė, and others. Among these, the best known are the heads of Nijolė Ulėnienė and his wife Gražina.

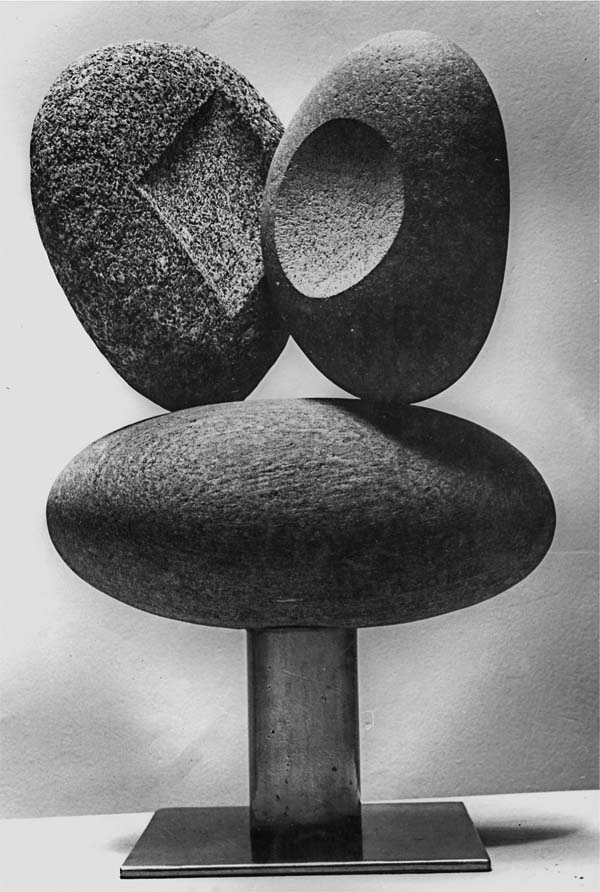

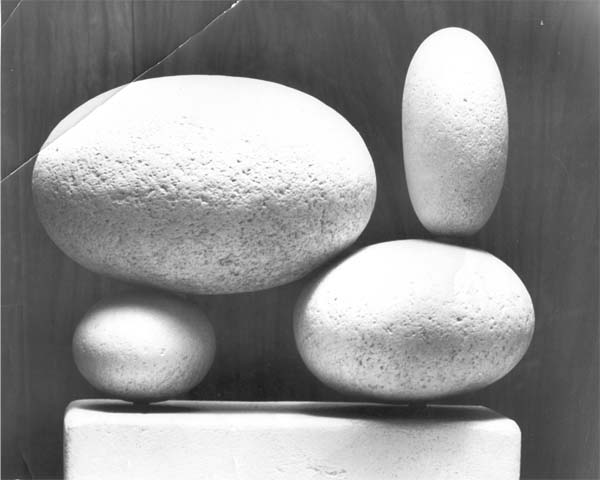

Vitolis collaborated with Albinas Elskus and Vytautas K. Jonynas, who had their studios in New York, by sculpting large religious cemetery monuments in Rye Brook, New York, and Greenwich, Connecticut, but he did not keep a record of the many religious sculptures he created for churches and cemeteries. He was in that respect like Viktoras Petravičius, who also did not keep a record of his works, but unlike Viktoras Vizgirda, who kept a diary. Like many sculptors, Dragunevičius mounted very few exhibits. In 1955, he exhibited his sister’s portrait at the Boston Arts Festival. He participated in a group show at the Galerija in Locust Valley on Long Island, proving to be an excellent craftsman and an outstanding sculptor. Besides group shows, as far as I know, Vitolis had only one oneman show, in 1970, at the Židinys Gallery in New York, professionally photographed by Vytautas Maželis. There, among portraits, Vitolis exhibited his abstract stone compositions. The stones came from the shore of Maine, where his artist friend Pranas Lapė had a summer cottage and studio. Round or oval in shape, naturally polished by the Maine surf, they were beautifully arranged on a variety of pedestals.

Modern simplicity interested Vitolis as much as Greek art. He was open to and appreciative of all movements and schisms, but preferred to stay with classical beauty. In spite of the fact that he lived most of his creative life in New York during the era of Pop and Op, conceptual and minimalist art, Vitolis remained a true follower of Maillol, the Catalan from Paris, a classical sculptor who made some forays into abstraction. The Neo-Dada and Fluxus movements of his countryman Jurgis Mačiūnas did not attract him.

Vitolis lived in Mamaroneck, New York, with his wife,

two daughters and three grandchildren and is buried in Saint

Xavier Cemetery on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. It would be best

if his archives and art works were transferred to Lithuania for

preservation for posterity.

|

|

|

Kęstutis J. Valiūnas, bronze,

c 1965. Photo by V. Maželis

|

Andrius Valiūnas, bronze. c 1965. Photo by V. Maželis |

Abstraction, Granite, New York, c 1970.

Abstraction, Maine stones, 1970.