Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 57, No.4 - Winter 2011

Editor of this issue: Patrick Chura

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 57, No.4 - Winter 2011 Editor of this issue: Patrick Chura |

M. K. Čiurlionis and the East

ANTANAS ANDRIJAUSKAS

ANTANAS ANDRIJAUSKAS is a professor at the Vilnius Art Academy and at the Vilnius University Center for Oriental Studies. In 2003, he was awarded the National Prize for Lithuanian Scholarship for his series of works, Comparative Research into Culture, Philosophy, Aesthetics, and Art.

Abstract

The oeuvre of M. K. Čiurlionis cannot be ascribed to any one art

movement. Scholars over the years have attempted to trace the

influences that determined the development of his unique style. In this

essay, Prof A. Andrijauskas discusses the pivotal role of the Far East,

particularly the influence of Chinese and Japanese landscape painting,

on Čiurlionis’s work.

Introduction

Mikalojus Kontantinas Čiurlionis lived only thirty-five years, but he left behind four hundred musical compositions, over two hundred paintings, as well as seven hundred fifty sketches, etchings, photographs, and prints. All of this represents the creative output of ten years, six of which were devoted mainly to painting. A century after his death, his legacy at last has reached Western Europe, Japan, and the United States. During the twenty years of its restored independence, Lithuania has organized twenty international exhibits of Čiurlionis’s work in Paris, Tokyo, Frankfurt am Main, Köln, Grenoble, Bellinzona, Warsaw, Kiev, Berlin, Milan, and elsewhere. Also, included in the exhibit “Visual Music” (2005) at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA), and at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., were three of Čiurlionis’s paintings—his cycle “Sparks” and, in Washington, Sonata No. 6, also known as “Sonata of the Stars” [1908]. This was the first time that Čiurlionis was shown in the United States on an equal footing with eighty other artists of international repute.

Lituanus, in its fifty-seven years of existence, has published many special issues and essays on Čiurlionis. Perhaps the most significant addition to the scholarship on his art and music that has come from the United States is a bibliography in English. Furthermore, every year at least one book or catalogue on his recently in Italian for an exhibit in Milan.

However, one area that has escaped closer scrutiny is Čiurlionis’s connection with the Far East, and with China and Japan in particular. This essay provides the opportunity to gain a deeper insight into the painter’s art in terms of its relationship with Eastern philosophy and art. In the past, Lituanus has focused on analyzing the Lithuanian painter, musician, and writer within the context of the West. As we commemorate the centenary of his death, it is fitting that we open still another door that may lead to a better understanding of Čiurlionis, this time with a view to the Far East.

As a final note, the translator of this essay is Birutë Vaičjurgis Đleţas, known in the Lithuanian community for her work in culture and the arts. She has performed as an actor, was co-founder of the Peabody-award-winning radio program “Garso Bangos”, has produced films and plays, and has translated articles published in Lituanus and Lithuanian Heritage magazine. She was one of the editors of Čiurlionis: Painter and Composer (1994).

Stasys Gođtautas

❖❖❖

In order to understand Čiurlionis’s mature painting style, one needs to examine its obvious connections with the great civilizations of the East in terms of their mythological symbolism, painting aesthetic, and fine arts traditions. The comparative method applied in this abbreviated study, which primarily focuses on landscape painting, supports the conclusion that Čiurlionis’s worldview and oeuvre reflect the influence of East Asian culture. His knowledge of Eastern art determined the development of the “musical painting” of his “sonata” period and the characteristic features of his art, including his spatial perception, his aerial view of the world, his concept of man as being one with nature, the subtle color palette of his later paintings, and the significance of the fluid line in his compositions.

Čiurlionis, as a painter, was drawn toward genuine creativity and was receptive to a broader range of influences than research studies have touched on. During his childhood, he became interested in Eastern civilizations and in his teenage years, when he played in Prince Ogiński’s orchestra, he saw Asian art in the prince’s palace. Later on, the images, symbols, and art traditions of the East became an inseparable part of his worldview, spiritual interests, and creative oeuvre.

The art forms of the great civilizations of the East and the West, crystalized over the centuries, are often dissimilar, being based on different ways of experiencing the world, as determined by geography, the surrounding landscape, age-old cultural traditions, the relationship of man with nature, and many other factors. However, their differences have not precluded the exchange and diffusion of their various art forms and symbols over vast distances. Throughout history, one finds many examples of the East influencing the West.

In the present study, however, we turn our attention to a later wave of Orientalism, or more precisely “Japanism,” that appeared in the West during the second half of the nineteenth century and reached its culmination as the crisis in traditional Western cultural values deepened. Starting with the Impressionist era, we find individual Western artists who, having experienced the authenticity and charm of Japanese prints, fell under their extraordinary spell and went on to effectively integrate the new creative principles that they discovered there. In doing so, they freed themselves from Eurocentric conventions, stepping over the boundaries of their own cultural tradition. Their motives were various: revolt against the decadence that dominated Western art; the search for new wellsprings of ideals, inspiration, and means of artistic expression; a spiritual attraction to other philosophies of life and to a different way of seeing art and the world; individual personal aims, and so on.

The various neo-Romantic movements gaining strength (Symbolism, Art Nouveau, Style Moderne, Jugendstil, Sezessionstil, Arts and Crafts, Stile Liberty, Stile Floreale) were not satisfied merely with restating Eastern themes in a literary manner, as had been the case during the Romantic period. In Postimpressionism there was a clear attempt to comprehend the essence of the East Asian painting aesthetic. The musicality of Japanese and Chinese art fascinated many noted artists of the time, including Frantiđek Kupka, Wassily Kandinsky, Oskar Kokoschka, Alfred Kubin, Paul Klee, James Ensor, Félicien Rops, Evgeny Lansere, and Mstistlav Dobuzhinsky. Gustav Klimt, the leader of the Vienna Secession, was an avid collector of Asian art and owned some fine Japanese prints and Chinese paintings, as did Aubrey Beardsley, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, Maurice Denis, Odilon Redon, James Whistler, Aleksandr Benois, and others.

The neo-Romantics were attracted not only to the metaphysical but also to the formal decorative aspects of Japanese and Chinese art that they found in the visual as well as in the applied arts, such as ceramics, lacquerware, and painted screens. In their attempt to uncover the hidden symbolic essence of depicted phenomena, they borrowed concepts and techniques from East Asian painting: freedom of artistic ideas, improvisation as the seed of creativity, the illusion of boundless space, the tendency toward refined ornamentation. In ukiyo-e prints, then popular in the West, painters discovered unusual approaches to composition, musical linear designs, dynamic sinuous lines, a succinct style. From decorative screens, they borrowed features typical of Japanese painting: asymmetrical composition, arabesque shapes, the magnification of individual details, the repetition of forms, the concept of unfinishedness (i.e., the non finito principle), blank surfaces in paintings that correspond to pauses in music.

The Symbolists had a fondness for the line drawing (ligne symbolique, ligne sezession, Schallwelle der linie) and the drawing en négative, which evolved under the influence of the Japanese katagami school and became popular in printmaking, book illustrations, and the vignette genre. Linear elements and musicality grew abundant in painting as well. There was a proliferation of stylized animals, birds, butterflies, dragonflies, insects, and floral images that reinforced the concept of constant movement, change, and growth. Decorative motifs from nature that first originated in Japanese visual arts gradually made inroads into other art forms. Unfortunately, many of the features that were introduced into Western art were copied in a mechanical way that often did not convey the refined quality typical of the East Asian painting aesthetic.

As he searched for his own unique language of artistic expression, Čiurlionis could not have remained unaffected by the European fin-de-siècle obsession with Orientalism and with Japanism, which bore the imprint of the great Chinese art traditions. There were a number of factors that conditioned the role that East Asian art played in the development of Čiurlionis’s mature style. First of all, the civilizations of the East were considered the cradle of Western civilization in the prevailing Romantic view. Čiurlionis was familiar with popular theories that regarded the East as the source of Western languages, mythology, religion, art forms, and as the spiritual home of Romantic ideals.

Second, the intellectual climate of the first decade of the twentieth century simmered with a multitude of conflicting spiritual and artistic movements connected with the advent of modernist ideology and art practice. Academic Orientalism underwent essential changes. The ideas of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer that emphasized the importance of Eastern philosophy, religions, and mythology influenced a great many followers, as well as members of the Theosophical movement, to “turn toward the East.” Such views enjoyed great vitality in Čiurlionis’s milieu.

Third, many influential Russians, Poles, and, later on, Lithuanians disseminated lofty ideas that regarded their native cultures as “bridges” between the worlds of Eastern and Western civilization. This consummate mission of Lithuanian culture excited Čiurlionis, especially since the Lithuanian language was connected with Sanskrit, the source of Indo-European languages, and, therefore, with Eastern civilizations. According to Liudas Gira, Čiurlionis envisioned the future Tautos namai [National Cultural Center] prominently adorned with Far Eastern stylistic features.

You yourself, sir, have seen our barns and sheds. Their ridges and roofs are so similar to those of Chinese and Indian temples that, it seems, they could have been lifted and transported here from the most distant Asian lands. (Gira, 1911, No. 1, p.6.)

Finally, and probably most importantly, the uniquely sensitive Čiurlionis felt a spiritual affinity with the art traditions of the East in which he discerned a great many concepts and formal techniques that enabled him to realize his idea of “musical painting.” In Čiurlionis’s letters, statements, paintings and in the attestations of his contemporaries we find many references to the East. In Bičiulystë (Friendship, 1906-1907), a mysterious figure from the East, depicted in profile and carrying the sun in his hands, seems to symbolize the artist’s reverential attitude toward the cultural values of non-European civilizations. After visiting the Hermitage and the Alexander III museum in St. Petersburg, Čiurlionis wrote in a letter to Sofija:

I saw ancient Assyrian bricks with terrible winged gods, which (I don’t know from where) I seem to know well and feel that they are my gods. There were Egyptian sculptures that I liked immensely. (Čiurlionis, M. K., Laiđkai Sofijai, V, 1973, p. 49.)

Influenced by the Romantic ideas of the time, Čiurlionis regarded European culture as a component of one shared universal world culture. He extricated himself from the narrow confines of the Northern European viewpoint and turned his attention to the cultures of the ancient Hebrews, Assyria, Persia, Egypt, Babylonia, India, China, and Japan. He delved into their cosmology, mythology, epics, legends, philosophy, systems of religion,astrology, and art. The artist’s vocabulary of images, symbols, and metaphors that he assimilated from these Eastern civilizations, and his emphasis on their common roots as well as their interrelationship is evidence of his universalist worldview.

Thus, in Čiurlionis’s early “literary-psychological symbolism” period, we find images of the sun, the cosmic serpent, the mighty bird, the fish, the boat, the bridge, and the cosmic tree, which, through various permutations, become a sacred mountain, an altar, the Trees of Life, Knowledge, and Fertility, the pillar of the universe, the cosmic axis—symbolizing the internal axis mundi, the connectedness of the elements of Sky, Earth, Water, and Hell. The slowly growing vertical tree, apart from the axis mundi symbolism, is an expression of strength, majesty, dynamic life force, and the antithesis of the static existence of a rock. The tree and the rock together symbolize the microcosm, the constant metamorphosis of life. The uplifted tree branches and vertical lines of other plants represent ascent toward the heavens, eternity, the flow of life. Just as the evergreen stands for eternal life and immortality, the leafy tree is the constant renewal of the world, the cycle of resurrection and rebirth. Čiurlionis often imbued natural phenomena with human traits to emphasize man’s intimate connection with nature. In many of his pictures, the represented elements of nature, living creatures, and objects acquire an anthropomorphic, i.e., human shape (even mountains are like living beings). This pictorial, mythological, and religious iconography is depicted side by side with the abstract symbolism of geometric signs, numbers, and colors of Eastern mythology—the circular sign of the Sun, symbolizing the fullness of life and perfection; the triangle as the epitome of knowledge; the rectangle as stability. In the early pictures we also see various ornamentation of an Eastern derivation, the imitation of archaic script, naturalistic motifs, loud colors and a sensuous treatment of painted forms, such as Funeral Symphony (1903), Capricorn (1904), Morning (1904), The Flood (1904–1905), Creation of the World (1905–1906). Symbols associated with Old Testament culture dominate these paintings. Although we do find Eastern elements in Čiurlionis’s paintings (albeit typically disguised within a generalized symbolic form or within a color scheme), they are much more prevalent in his drawings as architectural silhouettes, ornamental structures, and symbols.

B. Leman, the author of the first monograph on Čiurlionis’s oeuvre, led researchers toward a scholarly view, which later became the standard reference, that linked his symbols and representations with images from Near Eastern and Indian civilizations.

The cult of the sun, this center of fire that entices us to unknown reaches of the Universe, and the wondrous idea of one beginning, uniting and spiritualizing a system that he governs, encouraged Čiurlionis to study ancient Persia and Egypt, and pulled him even farther—toward the very wellspring of ideas—toward the six systems of Indian religion and philosophy.” (Леман, Б. Чюрлянис, 1912, c. 12)

Another influential Russian art theorist, Vyacheslav Ivanov, in analyzing the Lithuanian artist’s work, speaks of the Lithuanian people’s innate or inherited animism, which “by its typical pattern, apparently corresponds to the humble apathy of Indian contemplativeness and to the melancholic Indian lack of belief in any sort of ‘reality’.” (Иванов, B.”Чюрлянис и проблема синтеза искусств,” Аполлон,1914, №. 3, c. 20.)

This traditional view was adopted and was later reinforced within Lithuanian research studies on Čiurlionis by S. Đalkauskis, who further developed V. Solovjov’s messianic ideas and asserted that the mission of Lithuanian culture, which straddles two worlds, the East and the West, is to serve as their synthesis. “Vydűnas, who grew up in a climate of German Western activism, felt a strong attraction to the passive Eastern ideal, so distant in terms of time and space. Čiurlionis, confronted in Poland by the individualism of Western culture, felt a great empathy for the cosmic universalism of the Eastern philosophical spirit.” (Đalkauskis, S., “Dviejř pasauliř takoskyroje,” Rađtai, 1995, vol. IV, p. 173.)

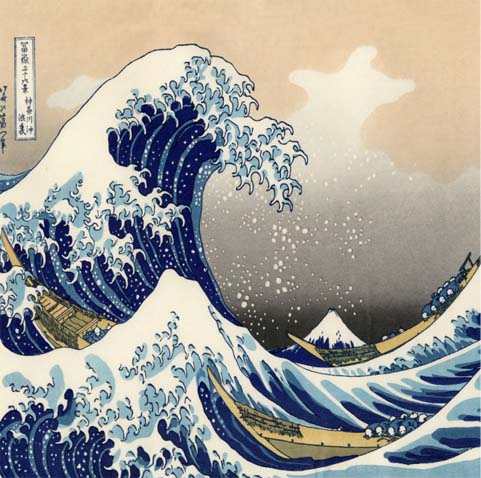

These Čiurlionis scholars as well as others (I. Đlapelis, A. Rannit, V. Landsbergis, I. Kato, G. Kazokienë, N. Tumënienë, R. Andriuđytë) have examined the symbols and iconographic elements of the Hebrew, Near Eastern and Indian civilizations that are clearly evident in his works. However, except for discussions of a general nature regarding the undeniable influence of the Japanese master Hokusai, the far more significant problem of connecting Čiurlionis’s landscape painting with that of East Asia still remains outside the purview of scholarly art research.

East Asian Influences in Čiurlionis’s Works

The only Čiurlionis scholar who has made any supported allusions to Čiurlionis’s connection with traditional Chinese art is Aleksis Rannit, though he, too, limits himself to fragmentary musings about an analogous “spiritual resonance” with the creative energy of the Universe, its dynamic expression in both traditional Chinese art and in Čiurlionis’s art. The art scholar accurately observes:

Creative dynamism was for the Chinese an absolute principle, an immanent activity of the tao, which was itself placed at the origin of all things as a force regulating universal spontaneity. In Čiurlionis, too, the impersonal and unchanging spirit beyond the presence of the self is felt as the fountainhead of his painting and as the goal towards which the artist cuts through chaos, regulating and organizing existence.” (Rannit, A., Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis Lithuanian Visionary Painter, Chicago, 1984, p. 77.)

Rannit quotes the noted Ch’ing dynasty era theoretician and artist Lu Chi (261-303) who asserts that “I can contain infinity in the space of a square foot of paper” and who muses that the thoughts and creative work of the true artist meld with absolute Thought and flow completely unfettered. Rannit states:

Similarly, Čiurlionis’ individual psyche seems to be reabsorbed through his art into the great cosmic Soul, as the flow of creative action springs forth from him like water. In this moment of grace, creation becomes for him a perfectly spontaneous act, and the harmony of his painting becomes sufficient unto itself as the expression of interior fullness. (Ibid., p. 77.)

We do not have any precise information as to when Čiurlionis first saw the work of East Asian artists and how he developed his knowledge of this distinct artistic tradition. As previously noted, East Asian art enjoyed great popularity in the West at the turn of the century. Čiurlionis may have been introduced to the masters of traditional Chinese and Japanese painting while studying at the conservatory of Leipzig or at the Warsaw art school. Quite possibly he saw Japanese art exhibited in Warsaw, in art shows he frequented at the Zachćta gallery, A. Kriwult’s art salon, and elsewhere. While pursuing his interest in non-European cultures, Čiurlionis would have come across art magazines and general art histories in French, German, and Russian with examples of Japanese art. The fine reproductions he found there would have allowed Čiurlionis to appreciate the rich color palette, the boundless space, the allure of the sinuous fluid line, and the succinctness of artistic expression characteristic of Japanese art. The uniqueness and the unusual solutions to problems of perspective, composition, and color that this art offered were subjects widely discussed by contemporary art critics and by various groups of young painters. Later on, in St. Petersburg, Čiurlionis associated with members of the Мир искусства (Mir iskusstva, World of Art) group, who were ardent admirers of East Asian art, actively promoting it in their work and in various periodicals. Čiurlionis also saw works of Japanese art in the home of Dobuzhinsky.

East Asian works of art, with their exaltation of nature, dizzying spaces, and ineffable poetry, could not have failed to affect a sensitive artist like Čiurlionis, who must have felt the spiritual affinity, the internal artistry, and powerful potential of the pantheistic visions expressed within them. He delved into them and understood their spirit intuitively, unlike many of his predecessors and contemporaries, who primarily looked only at the external and superficially impressive aspects of East Asian art.

The earliest conclusive and clearly documented evidence of Čiurlionis’s exposure to East Asian art is found in an account of his trip to Western and Central European centers of culture. In a letter from Prague to his benefactor and close friend, B. Wohlmann, dated 1 September 1906, the painter lists the works he has seen in that city’s museums and mentions Japanese panneaux, robes, and textiles. (Čiurlionis, M. K., Apie muzikŕ ir dailć, Vilnius, 1960, p. 195.)

This reference to Japanese panels provides a significant clue to the artistic influences in Čiurlionis’s work, because the most popular genre in Japanese painted folding and sliding screens was the landscape, which was heir to the great Chinese art tradition. Though the latter underwent some modification after being exported to Japan, it remained viable until the end of the nineteenth century. Thus, there can be no doubt that Čiurlionis was familiar with the art traditions of East Asia. The question of how deep and multifaceted this knowledge was can be answered by comparing the stylistic and formal aspects of Čiurlionis’s art with those of the East Asian art that inspired him.

During the winter of 1906-1907, Čiurlionis entered the second stage of his creative development, which was marked by a pursuit of new and complex means of artistic expression. We see greater spontaneity and decorativeness. He makes more frequent and noticeable use of the curving ornamental line, as, for example, in the cycles Sparks (1906), Winter (1906–1907), Spring (1907–1908), Summer (1907–1908), and in the paintings Night (1906), and Mountains in the Mist (1906). Incidentally, the seasons and nature motifs were the favorite themes of the painted Japanese screens that he saw in Prague.

Čiurlionis, like the painters of East Asia, seemingly sought to convey the inner “breath of the spirit,” the most profound flights of the soul, and did not spurn natural splashes of paint. Individual paintings within the above-mentioned list share a similarity with the paintings of Koetsu and Sotatsu, the masters of the Kyoto school, in terms of their spontaneity, color palette, and motifs. This impression is reinforced in the paintings Flowers (1907–1908) and Spring (1908). In close communion with nature, in a trance-like state, Čiurlionis created compositions filled with waterfalls, streams, delicate slender branches, butterflies, decorative insects, blades of grass, and muted color washes. Their decorative quality is primarily achieved through formal expressive means, through a stylized drawing containing elements of calligraphy, through musical arabesque forms, sinuous lines charged with vitality, and the emotional power of color tones and half-tones. His color palette, concept of space, abstract flowing shapes, and the musical lines represent important organizing principles within the compositional structure of his paintings.

One may suggest an explanation for the changes that are evident in his creative output during this period. As Čiurlionis visited the museums and galleries of Europe, he had the opportunity to critically evaluate Western contemporary works that predicted the dawn of modernism and to compare their achievements with those of East Asian art. The first-hand knowledge he gained from the experience pointed him toward solutions that enabled him to realize his creative goals. And, indeed, the important turning point that would come later in his creative evolution was coming into view. The plastic language Čiurlionis was beginning to acquire prefigured some aspects of the abstractionism and poetic surrealism that would later spread throughout Western culture. The link with East Asian art became a sort of key that opened the door for Čiurlionis into the qualitatively new mature musical period of his “sonata” painting style. The insights Čiurlionis gained from the masters of Japanese printmaking enabled him to recognize the core elements of Japanese painting that are connected with some of the finest examples of painting to be found in the history of world art.

Translated and edited by Birutë Vaičjurgis Đleţas

Photographs by Krescencijus Stođkus

National Museum of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis

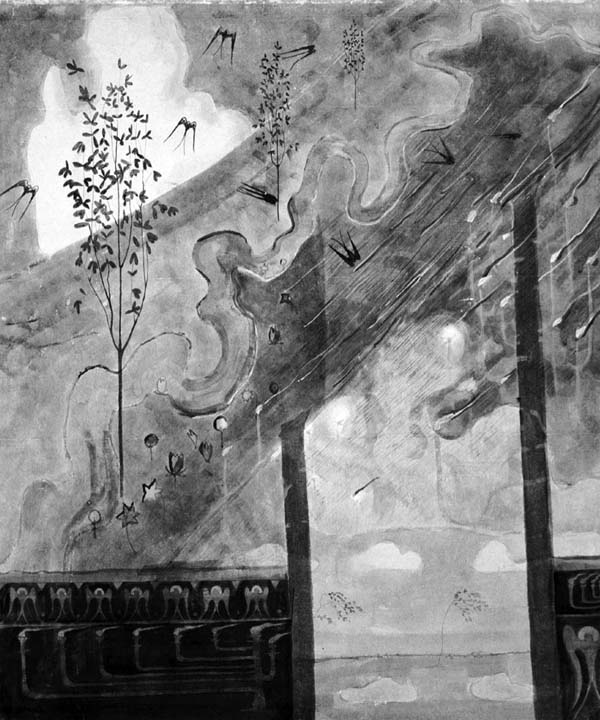

Sonata No. 2, (Spring), Scherzo. Tempera on pasteboard, 1907.

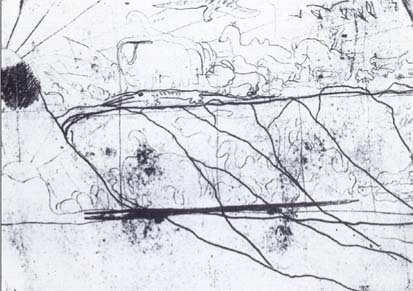

“Worship of the Sun.” Pencil sketch, 1908

|

|

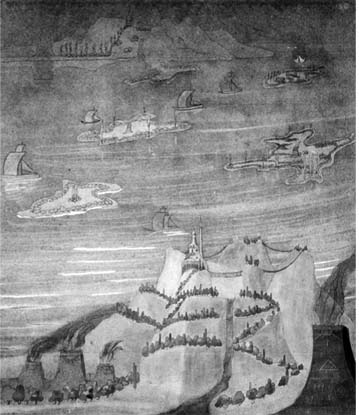

| Landscapes of the Four Seasons atributed to Shuban. Ink and colors on paper. About mid-fifteenth century. | |

|

|

|

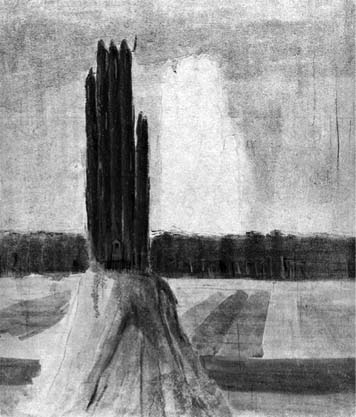

Sonata No. 4 (Summer),

Allegro. Tempera on pasteboard. 1908.

|

Summer II. Tempera on

pasteboard, 1907–1908.

|

|

|

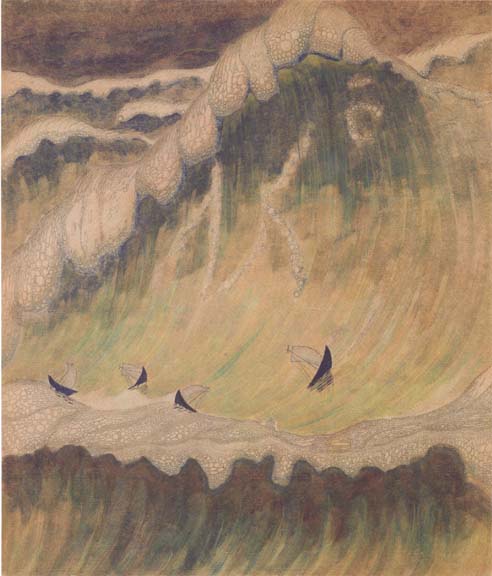

| Sonata No. 5 (Sea), Finale. Tempera on pasteboard, 1908. |

Hokusai. The Great Wave of Kanagawa (from a Series of “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji”), 1831. |