Copyright © 2012 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 58, No.2 - Summer 2012

Editor of this issue: Loreta Vaicekauskienė

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2012 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 58, No.2 - Summer 2012 Editor of this issue: Loreta Vaicekauskienė |

Language Standards in a Postmodern

Speech Community:

Cosmetic Touch-ups and Ongoing Changes

LORETA VAICEKAUSKIENĖ

Abstract

This paper examines how postmodern social reality influences the

attitudes of speakers and discusses the relation of social values to

language development. Sociolinguistic research indicates that the

nature of standard languages may be changing. Yet, without a study of

attitudes, we cannot say if the other varieties, which are gaining in

value, affect the status and functions of the standard language.

Besides, without systematic research we cannot be sure if the social

changes mean an ongoing reconstruction of the hierarchy of speech

varieties. This article focuses on values assigned to standard

Lithuanian, the speech of the capital Vilnius, and dialect speech. It

presents an experimental study carried out in schools of South

Lithuania and shows that measuring both conscious and subconscious

attitudes is instrumental in revealing different value systems

attributed to the studied speech varieties.

We can do justice to our time only by comparing it to that of our grandfathers and great-grandfathers. Something happened, whose importance still eludes us, and it seems very ordinary, though its effects will both last and increase. [...] It is determined by humanity’s emergence as a new elemental force; until now humanity had been divided into castes distinguished by dress, mentality, and mores. [...] Humanity as an elemental force, the result of technology and mass education, means that man is opening up to science and art on an unprecedented scale.

Czesław Miłosz, The Witness of Poetry, 1983

The multidimensional and mobile postmodern way of life has added an extra flavor to cultural and linguistic diversity. The hitherto known and more or less homogenous social structures have split into overlapping communities of practice, constructing mixed and complex social identities and thus forcing their members to extend their linguistic repertoires.

These changes may be radical for the status and perception of language varieties and standard languages. It seems that greater linguistic diversity is being tolerated. As local patriotism strengthens, regional and social dialects are gaining in value, and new linguistic norms for particular domains are being formed. Researchers from various speech communities report similar observations: linguistic varieties and features are socially loaded and they do serve as an important resource for the creation of the needed social identity in a given situation and space.1 That is: one established and invariant standard provides an insufficient number of options for the postmodern role-play with social values.

The question then is how many “standards,” or how much variation within “the standard” can be expected as the consequence of this changing social reality. Can a regional dialect acquire a status tantamount to standard language (SL)? Can urban speech, traditionally not attributed to SL, replace it in certain domains? The fundamental question in this relation is the notion of SL. It varies depending on how language diversity, variation, and development are perceived.

In sociolinguistic theory, the SL is conceived of as an integral part of the ideological development of the given society. It is through language use that the SL is formed. The concrete choices of speakers gradually change the SL – either filling it up with new features or swapping it for another variety. This linguistic conduct depends on changing social values. Not language standardization policies, but language actors – the users of the language – and their (not necessarily overtly expressed) judgments are seen as the decisive force for language development:

[…] the attribution ‘standard’ must reflect social judgments and social practices in the community rather than descriptive details of varietal range and variation. […] It is likely that the process of standardization will be understood quite differently by those engaged in top-down agentive roles and by others, ‘the people,’ who make on-the-ground assessments of the social implications of using different ways of speaking. Top-down discourses of language standardization may not overlap with on-the-ground discourses, and the social judgments that matter most may even remain below the level of metalinguistic formulation.2

It seems rather logical then that the notion of SL should follow the changing reality. However, as the quotation also implies, this is not always the case when involved with official ideologies.

In Lithuania, the distance between language policies and the choices of speakers (language development) is especially prominent. In the overt discourse of language planners, the SL is presented as a homogenous speech variety; the interference of other (social, dialectal) varieties is seen as corrupting the fixed norms and “boundaries” of the SL. The “permission” of language planners is not a metaphor in the Lithuanian context, because the preplanned version of the SL is protected by law. The natural development of language is presumed to go in the wrong direction, and therefore must be regulated. The many gatekeeping institutions keep on opposing diversity, prescribing the norms for “correct” language usage, and attempting to influence the attitudes of the speakers. The SL is definitely placed at the top of the hierarchy of speech varieties of Lithuanian. Heterogeneous and variant urban speech, especially the speech of the capital, Vilnius, is given the lowest position.

Compared to Soviet times, official attitudes are becoming more favorable toward dialects. This is most likely due to the recognition that the standardization ideology and the development of society have accelerated the process of dialect leveling. However, dialectal speech is seen mostly as an object for preservation and as a valuable marker of ethnic heritage (alongside folk dance, traditional clothing, and other local specialties), rather than a means of public communication. Cf., National language policy guidelines for 2009–2013:

The standard Lithuanian language, as the uniting force for Lithuanian society, has to be continually nourished, with the state and society combining their efforts. Lithuanian dialects are a linguistic and cultural heritage; they serve important functions for the local community and, therefore, have to be protected and supported.3

The issue addressed in this paper is how much the prescriptive policies can influence the ideological development of our society. What social values do ordinary people assign to the speech varieties SL, urban speech, and dialect? What do their attitudes reveal about the development of the SL, and what role is given to and played by Vilnius speech? And finally, is postmodern linguistic diversity just a new cosmetic touch-up, or has it commenced a process of reconstruction and replacement in the hierarchy of speech varieties in the Lithuanian speech community?

In this complexity, these research questions are raised for the first time in Lithuanian linguistics; however, incidental remarks on the Lithuanian situation can be found outside our scholarship, cf.:

The question is what are the prospects for interaction between the established norm and the living speech of the cities and to what extent may the latter come to influence and change the former. At present, the dominant linguists are firmly in control of the strictly formulated and well-guarded standard norms.4

In order to obtain both overt and metalinguistically unformulated, subconscious attitudes, an experimental study was carried out in some schools of the Marijampolė region (South Lithuania). Young people are especially interesting to question because their attitudes can give us a hint about ongoing changes in social values and linguistic conduct. The next section describes why it was important to examine both conscious and subconscious values and what methods were applied in the research.

“Two value systems at two levels of consciousness”

The quotation used for the title belongs to Tore Kristiansen5, whose work on language attitudes in the Danish speech community over the last twenty years equips us with an elaborate set of research instruments and a number of insights into the existence of covert values and their possible role for language change. Sociolinguists believe that behind any socially significant language variation lie the attitudes of the speakers. Danish research has proved that consciously offered attitudes support the official ideologies and reflect their system of values, while the positive covert judgments, as far as it is ensured that they were elicited as subconscious assessments, support the overtly downgraded varieties and explain why they are still used. Subconscious attitudes thus correspond to what is happening on the level of language use and may demonstrate a quite different system of social values.6

The idea of our research was to check whether the linguistic diversity seen in “real life” would be supported by positive subconscious values that young people attribute to the speakers of given speech varieties of Lithuanian.

The research was carried out with 226 ninth and tenth grade students (15 to 17 year-olds) in the schools of three smaller sites (Kalvarija, Vilkaviškis and Pilviškiai) situated around the regional center, Marijampolė. In order to compare possibly different systems of social values, two methods of attitudinal research were applied: (1) a speaker evaluation experiment (SEE), where the informants listened to short clips of recorded speech and evaluated the personality traits of the voices played and (2) a label ranking task (LRT), presenting a list of labels of varieties that the informants had to rank according to which one of them he or she liked most.

The SEE was designed to reveal the subconscious attitudes of the students, and the LRT should reflect their overt, conscious opinions.

The speech varieties evaluated by the students were: the SL (in the SEE called Conservative speech, C), Vilnius speech (called Modern speech, M) and Marijampolė speech (called Local speech, L). Two female and two male voices represented each of the three varieties (twelve voices total). They were recorded in the schools of Vilnius (the C and M) and Marijampolė (the L) and all had the same topic “what is a good teacher.” The twelve clips were each approximately fifteen seconds in length and made so that their content (the opinion about the teacher) and form (fluency, voice quality) were as similar as possible. The main remaining difference was the varying speech features.

What we relatively call the C in our research is a speech variety that contains some phonetic and prosodic features of the codified SL: the long or at least semilong vowels in unstressed syllables; the (semi)long unstressed vowels o and ė; no stress attraction. This variety is described in the textbooks on standard pronunciation and is supposed to be taught at school. However, it is very seldom found among youngsters, and what you can record, if you are lucky, is just conservatively accented speech.

The M voices in our research contain features characteristic of the speech of Vilnius, which are said to be spreading in contemporary broadcast language: foreshortened long vowels in unstressed syllables; short and broadened o and ė in unstressed position; monophthongization of ie in unstressed syllables; stress attraction.

The L represents the speech of the pupils in the biggest city of the research area, Marijampolė. Since the idea of the experiment was not to attract the attention of the informants to the language itself, the recordings were edited so that they contained just a few dialect features – first and foremost, intonation and long tense o, which are typical for this regional dialect. However, the local dialects were not to mix with the rest of the dialects – and this is always the case with the southern subdialect of West Highland. Though this dialect is closest to the SL, its specific features are said to be the most difficult to hide.

Performing the SEE, the students were not aware that they actually assessed speech varieties. After the experiment, they were asked what they thought all this was about, and they guessed that we were studying opinions about teachers. The second test, the LRT, was performed with the informants aware of the purpose of the research. This means that we succeeded in collecting both conscious and subconscious attitudes and can compare the results and discuss what city the young people in the Marijampolė region prefer as their linguistic norm attraction center, and which linguistic features index the kind of social identity they favor.

Conscious evaluations: diversity is welcomed

The informants were presented twelve labels of speech varieties and had to rank them from one, as the highest, to twelve, as the lowest. The results from all three sites are summed up in Table 1, highlighting the three varieties used in the research: Vilnius speech, Standard Language (Bendrinė kalba) and Marijampolė speech. Although the positions of the varieties studied at first glance imply the ranking: Vilnius > SL > Marijampolė (the lower the ranking, the better the evaluation), i.e., overtly upgrading Vilnius, downgrading SL and further downgrading the local speech, this is not so straightforward. Firstly, there is no statistical difference between the rankings of Vilnius and SL. Secondly, local patriotism should be judged not just from the ranking of downgraded Marijampolė, but also from the high ranking of Vilkaviškis speech. In the school of Vilkaviškis, the Vilkaviškis speech was placed at the top of the list, and in nearby Pilviškiai, it was the second highest after Vilnius. In the Kalvarija site, which is closest to Marijampolė, Marijampolė speech got the second highest ranking after Vilnius.

Table

1

Ranking of the speech labels in Marijampolė region

1

is the highest rank

| Mean rankings |

||

| 1. | Vilnius speech | 4.0 |

| 2. | Vilkaviškis speech | 4.4 |

| 3. | Standard Language (Bendrinė kalba) | 4.9 |

| 4. | Kaunas speech | 4.9 |

| 5. | Marijampolė speech | 6.1 |

| 6. | Klaipėda speech | 6.2 |

| 7. | Alytus speech | 7.1 |

| 8. | Šakiai speech | 7.2 |

| 9. | Panevėžys speech | 7.6 |

| 10. | Šiauliai speech | 7.7 |

| 11. | Utena speech | 7.8 |

| 12. | Telšiai speech | 8.9 |

Thus the relevant local speech varieties are favored locally at least no less than the other “important” varieties. Downgrading of the regional center, Marijampolė, was most probably caused by the inclusion of the label Vilkaviškis speech and splitting the evaluations of dialect (as stated above, Vilkaviškis was chosen in favor of Marijampolė as more local in two of the sites). Yet this may also be a sign of a general attitude towards Marijampolė speech in Lithuania. While Vilkaviškis counts as a local reference, Marijampolė may be considered representative of the whole West Highland dialect. As mentioned before – the accent of the dialect is difficult to hide, even when speaking SL, and the speakers who have this accent may be sneered at. Since it is stigmatized, the accent is used in the media for comical characters. That may have formed a negative stereotype of Marijampolė speech.

The question remains why Vilnius speech scored so high – equally as high as the “neutral” or “more local” dialect of Vilkaviškis and the traditionally valorized SL, when urban language is referred to as mixed and polluted in official discourse. As discussed above, consciously offered values reflect the overt attitude, usually the official one, where preference is given to the SL. One possible answer could be the differing notions of the SL in language planning discourse and by lay people. Research shows that Vilnius speech is equated with the SL by ordinary speakers.7 In the Marijampolė research, the Conservative voices were allocated to Vilnius by a bigger percentage of informants than the Vilnius speech itself (75 percent versus 64 percent, respectively). This can be an important hint that on a conscious level “The Standard” is becoming more connected with the capital Vilnius, and therefore the label “Vilnius speech” moves higher in the overt ranking. But then, of course, it is a bit strange that the label “Standard Language” was not used for that purpose. Another possible explanation could be that “Vilnius speech” and “SL” are perceived as synonyms.

All in all, we can say that, except for the stigmatized and, therefore, perhaps overtly downgraded Marijampolė dialect, the conscious evaluations offered by young speakers in the Marijampolė region show no hierarchization of the studied varieties (assuming that local was substituted by the Vilkaviškis dialect). This may be regarded as a crucial result for official standardization ideologies and the conservative SL, which for a long time enjoyed the status of the most overtly valorized variety. However, if we assume that the upgrading of Vilnius speech has to do with the confusion of Vilnius speech with the SL and the attributing of Vilnius speech to standard, then the results would reflect the continuing strong positions of standard ideology and the SL, which, however, is becoming more relaxed and extending its ideological boundaries to include Vilnius speech and thus accepting more internal variation.

Subconscious evaluations

As already discussed, the subconscious assessments, offered by judges who were unaware of the purpose of the research, are supposed to reflect what is happening at the level of language usage. When the presented voice is regarded as having more positive personality traits than the other voices, it is very likely that the features characteristic to his or her speech have a certain prestige and may be adopted in linguistic practice.

Before conducting the above described label ranking task, the students were played the twelve voices, representing the three studied varieties – Conservative (Standard language), Modern (Vilnius) and Local (speech of Marijampolė city). The four voices for each variety were played in turn: C, M, L, switching between girl (g) and boy (b), i.e., 1_Cg, 2_Mb, 3_Lg, 4_Cb, 5_Mg, 6_Lb, etc. The mixing of the voices and the same topic (“a good teacher”) helped us to avoid attracting the attention of the judges to the language issue and thus to ensure that we elucidated subconscious attitudes.

While listening to the voices, the students were instructed to tick off the personality traits of the speakers on the eight seven-point adjective scales (see following table).

Table 2

The adjective scales used for the Speaker Evaluation Experiment

| Goal-directed | Indecisive | |||||||

| Trustworthy | Untrustworthy | |||||||

| Conscientious | Happy-go-lucky | |||||||

| Fascinating | Boring | |||||||

| Self-assured | Insecure | |||||||

| Intelligent | Stupid | |||||||

| Nice | Repulsive | |||||||

| Cool | Uncool |

The given personality traits are commonly used in attitudinal

research in similar lists. Traditionally, two evaluative

dimensions of social relations have been distinguished, viz.,

status and solidarity. However, the newest research from the

Copenhagen School has shown that including a couple of additional

aspects of the mentioned two may be more workable. An

elaborated model then operates with the aspects “superiority”

and “dynamism,” and I will use them later in the discussion of

the results.

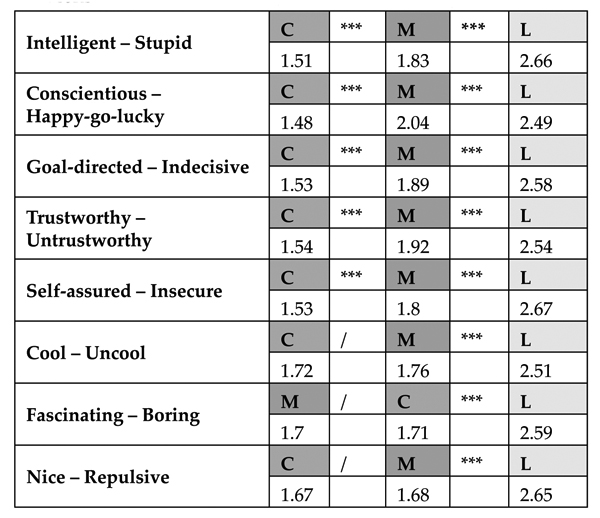

In order to ensure the validity of the results, the assessments were calculated as the mean rank values for all four voices in total for each variety (see following table).

Table 3

Subconscious assessments of C, M and L in the Marijampolė region

The values are ranked in decreasing order. The lower the rank,

the more often the voice is attributed to the left trait of the pair.

Wilcoxon: *=p<.05, **=p<.01,***=p<.001.

In contrast to the consciously offered attitudes, where the

local dialect (albeit not Marijampolė, but the linguistically very

similar Vilkaviškis) was equated with the other varieties, the

subconscious assessments point in the opposite direction. The

local voices yield to the standard varieties M and C in all traits

(the three asterisks in Table 3 indicate the statistically most

significant differences). It means that dialect speech is evaluated

as giving significantly fewer positive characteristics to the

speaker.

Meanwhile, the C gets more positive evaluations for the traits intelligent, conscientious, goal-directed, trustworthy and self-assured than both L and M. These social values might be ascribed to the dimension of superiority, and this is the set of values traditionally attributed to the conservative standard. As for the rest of the traits, the assessments of C show no significant difference from the assessments of M (the slash in Table 3 indicates no statistical significance). The latter is probably the most intriguing result of the research, since those three personality traits cool, fascinating and nice might be related to the “dynamism” evaluative dimension. Attribution of these traits to officially undervalued Vilnius speech in SEE means that Vilnius speech may gain or is gaining in value in domains that are related to a modern and dynamic style of life, that is, it is really acquiring the status of an acknowledged and prestigious standard variety. Moreover, M voices were allocated to Vilnius by merely 64 percent of the students in the research. The rest allocated M speech to other bigger cities. These results may imply that Vilnius speech is losing localization, i.e., spreading as a nonlocalized norm, and thus beginning to perform the function of the commonly used standard. If the theoretical assumption that subconscious attitudes point to on-going changes is to be taken seriously, we might expect Vilnius speech to be assigned the qualities of standard language and to be included in the extended concept of SL. In this new “standard,” the conservative standard will be assigned social values related to the “superiority” dimension, while the modern, Vilnius, speech will be attributed the values of dynamism.

To discuss

The research into attitudes towards linguistic diversity in the Lithuanian speech community conducted with adolescents in the Marijampolė region allows the formulation of several points for discussion… with varying degrees of certainty. We are most sure that linguistic diversity is tolerated to a greater extent when dealing with overt attitudes. The assessments of the students in the label ranking task (LRT) demonstrated the following pattern:

LRT: Modern / Local 1 / Conservative > Local 2.

The students demonstrated positive overt attitudes both towards the Conservative (SL), Modern (Vilnius) and Local 1 (Vilkaviškis) speech. With the exception of the Local 2 Marijampolė, either stigmatized or regarded as more distant than Vilkaviškis, the assessments of young people showed no hierarchization of the relevant varieties. These results are not very surprising, because people tend to overtly express positive evaluations, especially ones that are supported by official ideologies. In this respect, the upgrading of the officially denigrated Vilnius speech is a bit more surprising. Most probably it has to do with the belief that Vilnius speech is “The standard” and the label is the synonym of the label “Bendrinė kalba.”

Yet the consciously offered attitudes do not say much about language choice in linguistic practice. What will happen to our dialects in the future? Will local patriotism keep them alive, granting the regional dialect speaker social prestige? Or is it just a trend, a new cosmetic touch-up only practiced on certain occasions, and having no more than a declaratory character? How will the SL develop if the attribution standard is extended to include Vilnius speech?

The subconscious attitudes of the speakers can probably provide some more certain answers. In our research, the choice of the students could not be misinterpreted – the local voices were assigned significantly worse personality traits than either the Conservative (SL) or Modern (Vilnius) voices. This has sad implications for linguistic diversity with respect to one of its inherent elements – the dialects, at least in the Marijampolė region. Meanwhile, the acceptance of variation in and diversification of “the standard” is much greater, and indicates an ongoing distribution of positive values assigned to the C and the M speech – the personality traits related to superiority were ascribed to the C alone and the dynamism traits were shared by C with M, cf.:

SEE: Conservative > Modern > Local (on superiority traits)

SEE: Conservative / Modern > Local (on dynamism traits)

The spread of M features in the domains related to a modern, dynamic lifestyle has already been noticed and has been met with resentment by the gatekeepers8; indeed, Vilnius speech features are spreading in broadcasting, especially in popular entertainment and youth programs. This means that, in spite of the strict gate-keeping and regulation imposing ideal norms of SL and favoring the codified conservative standard, the development of language and the linguistic choices in a speech community are governed by natural self-regulation processes following the value systems in that particular period of time. The notions of standard language and conventions of speaking which fit in the changing spaces of social interaction are being formed and transformed by the speech community itself. Subconscious attitudes should play not a minor role in this process. All of this makes the interpretation task for the scholar more complicated, yet much more exciting.

Edited by Chad Damon Stewart

WORKS CITED

Aliūkaitė, Daiva. “Bendrinės kalbos vaizdinių tikslumas,” Respectus Philologicus, 16 (21), 2009.

Blommaert, Jan. “A Sociolinguistics of Globalization.” In The New Sociolinguistics Reader, eds. N. Coupland and A. Jaworski. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Coupland, Nikolas and T. Kristiansen. “SLICE: Critical perspectives on language (de)standardization.” In Standard Languages and Language Standards in a Changing Europe, eds. N. Coupland and T. Kristiansen. Oslo: Novus, 2011.

Gregersen, Frans. “Postmoderne talesprog.” In Københavnsk sociolingvistik.Oslo: Novus, 2009 (1995).

Grondelaers, Stefan, et al. “A perceptual typology of standard language situations in the Low Countries.” In Standard Languages and Language Standards in a Changing Europe. Oslo: Novus, 2011.

Kristiansen, Tore. “The macro-level social meanings of late-modern Danish accents,” Acta Linguistica Hafniensia, 41 (1), 2009.

_____. “Attitudes, Ideology and Awareness.” In The SAGE Handbook of Sociolinguistics, eds. R. Wodak et al. Sage, 2011.

Pupkis, Aldonas. “Ar turime prestižinę tartį?” Gimtoji kalba, 6 (384),1999.

Rinholm, Helge. “Continuity and change in the Lithuanian standard language.” In Language reform, eds. F. István and C. Hagège, Vol. V. Hamburg: Buske, 1990.

Vaicekauskienė, Loreta and R. Čičirkaitė. “ ‘Vilniaus klausimas’ bendrinės lietuvių kalbos sampratose,” Darbai ir Dienos, 56, 2011.