Copyright © 2012 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 58, No.4 - Winter 2012

Editor of this issue: Viktorija Skrupskelytė

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2012 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 58, No.4 - Winter 2012 Editor of this issue: Viktorija Skrupskelytė |

The May Third Constitution and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

LIUDAS GLEMŽA

LIUDAS GLEMŽA is a historian currently teaching at Vytautas Magnus University. Editor of two books, he has written extensively on social and political issues in seventeenth to early nineteenth century Lithuania, as well as on contemporary topics. His recently published monograph discusses city governance and related issues in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Abstract

The document known as the May Third Constitution continues to

provoke heated debate among historians as well as the general public.

Opinions divide sharply into positive and negative evaluations of the

document, as was evident in recent discussions that raised the

question:

should May 3rd be declared a day to commemorate? The article

attempts to shed light on the origin of the controversy, but also

argues

that the May Third Constitution, one of the first written national

constitutions

worldwide, demonstrates that the Commonwealth of Two

Nations (Lithuania and Poland) was not a backward, hopeless country

as it has been portrayed. The state and the society tried to institute

reforms, move ahead, and break out of its isolation. The last two years

of the Commonwealth’s existence saw major efforts to set the

course

of reforms. Even though the decisions of the Four-Year Sejm were

annulled

in 1793, they played an important part in the measures adopted

by the Grodno Sejm of 1793 and the uprising of 1794. The Constitution

shows that the collapse of the Commonwealth was caused by the

imperial ambitions of neighboring states rather than its own internal

weakness. The article also addresses the question of

Lithuania’s fate

under the Constitution, a question which continues to preoccupy

historians.

|

|

|

King

Stanisław August (left) enters St.

John’s Cathedral,where

deputies will swear to uphold the Constitution. Detail

of a painting by Jan Matejko, oil on canvas, 1891.

|

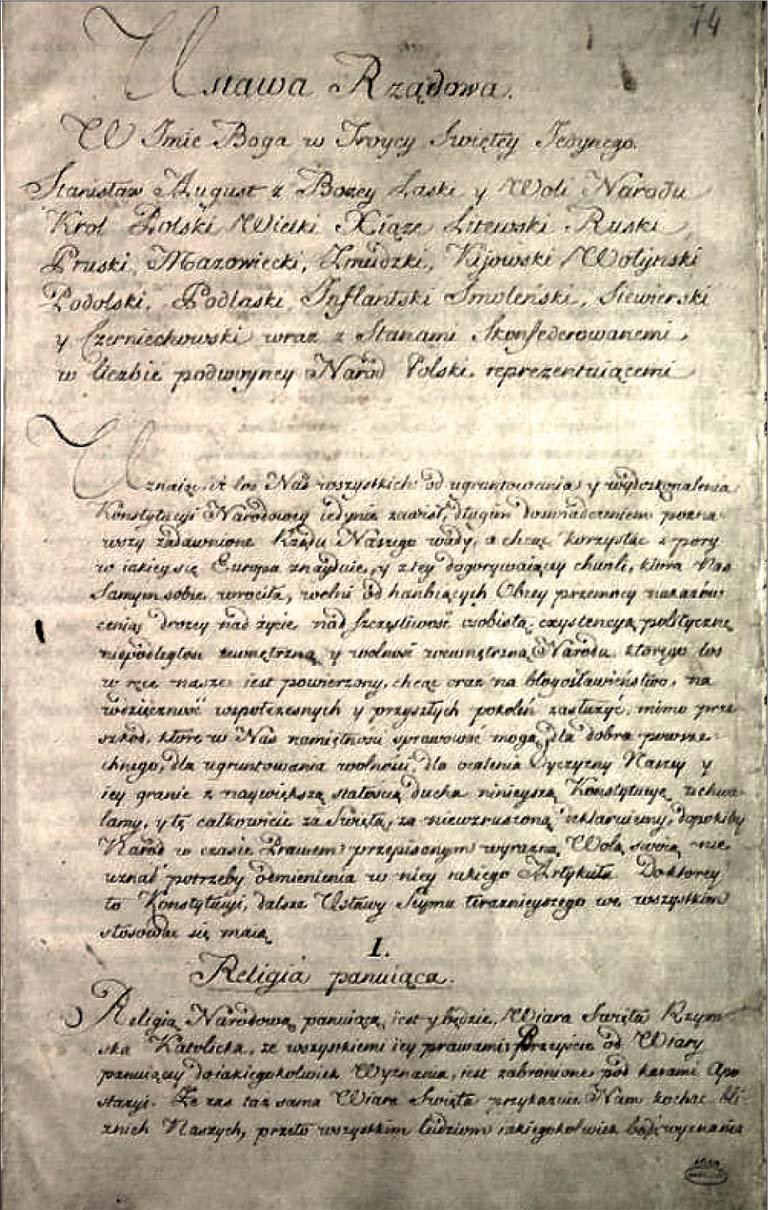

The manuscript of the May 3, 1791 Constitution. |

Introduction

The Constitution of May 3, 1791 arouses the greatest passions in the field of Lithuanian history, dividing both historians and the reading public into two camps with differing evaluations of the document. If one had to specify the balance of forces, I would say that the more popular camp in Lithuania today consists of the Constitution’s skeptics, for whom the May 3rd date is a memorable day, not so much in Lithuania’s history as in Poland’s. The first attempts to commemorate this day publicly were essentially not heard, while the efforts of Seimas deputy Emanuelis Zingeris in 2007 to declare the day of the passage of the Constitution a memorable day in the history of the Lithuanian state provoked heated discussions and disputes.1 The disputes were triggered by uncompromising arguments on both sides, while the most difficult task of all was for one side to hear the other and look deeper at the position of the opposing camp. Responding to the events, historians of Vilnius Pedagogical University (now Lithuanian University of Educational Sciences) prepared a public statement and later initiated a scholarly discussion entitled “Dar kartą apie Gegužės 3 d. konstituciją” (Once More About the May Third Constitution). During these discussions, historians reached a cautious general conclusion (more likely a compromise) and recognized the Constitution as a significant event in Lithuanian history. But the conclusion was not widely broadcast. The viewpoint of opponents was said to be “inaccurate” and was rarely heard, because questions of political importance (to commemorate the date or not) remained in the forefront. Mockery was expressed, making the discussion even more difficult, because in this way the very document of the Constitution and its era acquired negative connotations.2

At the international conference entitled Lietuvos Didžioji Kunigaikštystė XVIII amžiuje: tarp tradicijų ir naujovių (The Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Eighteenth Century: Between Tradition and Innovation), held in 2011 at the Institute of Lithuanian History, one more attempt was made to speak publicly about the meaning of the May Third Constitution. By joint agreement and without objection from either side, the conference reached the conclusion that the May Third Constitution was a significant document in Lithuanian history, not only in the history of Lithuania and Poland, but of the current Belarus and Ukrainian nations, at that time part of the Commonwealth of Two Nations, as well. It appears that this time both sides were better able to listen to each other.3 The purpose of this article is not to raise the question of whether or not the May 3rd date should be commemorated, but rather to direct attention to the significance of the document in Lithuania’s history and, at the same time, highlight the most important sensitive issues that remain unresolved and recur in the continuing discussions among scholars.

In its form and content, the document adopted on May 3, 1791 by the Sejm of the Commonwealth of Two Nations conforms to what we know as a constitution. Early on, its original name, An Act of Government (Ustawa Rządowa), fell into disuse and was replaced by a reference to the date of its adoption, hence the better-known name of the May Third Constitution.4 Essentially, at that time, every law adopted by the Sejm was called a constitution, but the May Third Constitution differed from the others because it alone defined the rights and freedoms of the citizens and prescribed the forms of governance and organization of the state. In its purposes and content, the document is not unlike the first national constitutions in Europe and the world, those of the United States of America (1787) and France (1791).

Looking from a broader perspective of historical events, one recognizes that the May Third Constitution yields to those of France and the United States, because the latter two declared the equality of all citizens before the law and in this way dismantled discriminatory class structures. Lithuania and Poland had a different history, and thus their societies were not prepared for the kind of changes that occurred in revolutionary France. Nevertheless, the May Third Constitution opened up possibilities for city dwellers to participate in the governance of the state; it softened the autocratic domination of the boyars, established separate legislative, executive and judicial authorities, and declared the Commonwealth a constitutional monarchy based on class. A provision in the text of the Constitution specified that the new order would not change for twenty-five years. This long-term perspective did not bar the way for immediate major reforms, which continued intensively up until July 1792, despite considerable opposition. At that time, army troops of the Russian Empire invaded the Commonwealth, advancing deep into the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland. King Stanisław August, the last ruler of the Commonwealth, capitulated and joined the Targowica Confederation, which was ill-disposed toward reforms. Thus the course of reforms that were only beginning and could have continued was broken off, despite the safety valve of the twenty-five year clause. Nevertheless, viewed from a broader historical perspective, it is clear that the May Third Constitution laid the foundation for fundamental social and political changes in the territories of the Commonwealth.

The circumstances of the passage of the Constitution

Reforms nurtured by the Commonwealth since the middle of the eighteenth century had met with considerable opposition from neighboring states, especially Prussia and Russia. However, a change in geopolitical circumstances changed the climate in favor of reform. The most important incentives came with the start of the Russo-Turkish war in 1787, which introduced elements of uncertainty into the situation. Dissatisfaction among the great European states was rising because of Catherine II’s ambitions in the Balkan Peninsula. A tripartite union against Russia was formed by England, Prussia, and the Netherlands; Sweden declared war in 1788, intending to free itself from Russia’s political domination. England supported both Sweden and Turkey. As tensions along the Russian border grew and military actions broke out on two fronts, against Turkey and Sweden, the situation in the Commonwealth changed in favor of reform because Russia no longer could devote sufficient attention to its neighbor. The Sejm assembled in 1788 and decided to increase the state’s military forces in order to bring it out of international isolation. At the beginning of 1789, pressured by the Sejm, Russia withdrew its troops from the territories of Poland and Lithuania, which allowed the boyars of the two countries to resolve internal conflicts without outside interference. That same year the French revolution began. The great powers fixed their gaze on Sweden, France, and the Balkans. The Commonwealth formed a military alliance with Prussia, at that time hostile to Russia’s imperial designs, even though two cities belonging to the Polish kingdom, Danzig (now Gdańsk) and Toruń, were the first targets of Prussia’s expansionist plans. The alliance was not strong, but it gave hope to the reform-minded leaders in the Sejm. Tensions in Europe persisted until the end of the Russo-Turkish war early in 1792, which created an interval propitious for reform.5 The Sejm continued to work for four years, thus acquiring the name of the Four-Year Sejm. Deputies elected to the Sejm in 1788 sat until the summer of 1792; their ranks were supplemented by new deputies, elected in 1790 (elections to the Sejm traditionally took place every two years).

The decision of the Sejm to increase the army of the Commonwealth to 100,000 soldiers meant significantly deeper administrative and social reforms, for without them the military plans could not have been implemented. It was clear that the boyars alone could not defend the state and that more potential defenders were needed. It was essential to modernize the state’s governing apparatus to make it more efficient. Since the neighboring monarchies of Prussia, Russia, and Austria were considered to be the best examples of well-run states, efforts were made to centralize the government following their example, taking into account local traditions. King Stanisław August, Marshall of the Polish Confederation Stanisław Małachowski, Poland’s Chancellor Hugo Kołłątaj, and Court Marshall of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (GDL) Ignotas Potockis (Ignacy Potocki) led the effort. They formed the core of the so-called Patriot Party. The king and his closest accomplices succeeded in drawing other nobles to their side, including Lithuanians, among them GDL Confederation Marshall Kazimieras Nestoras Sapiega (Kazimierz Nestor Sapieha) and GDL Vice Chancellor Joachimas Liutauras Chreptavičius (Joachim Litawor Chreptowicz). They were invited to some of the secret meetings, but were not made aware of everything. Since the king and his closest advisors (Kołłątaj, Małachowski, and Potockis) were the authors of the May Third Constitution, its contents became known only in the hall of the Sejm and did not meet the expectations of either Chreptavičius or Sapiega.

To ensure the ratification of the Constitution, the king and his band of reformers resorted to ruses. The Constitution was presented for discussion to the Sejm early in the session because the opponents of reform, traditionally late, had not yet returned from vacation. But supporters of reform were secretly informed of the necessity to be present at the May session from the very beginning. The election of deputies to the Sejm in 1790 had strengthened their (the Patriot Party’s) position, but they did not have a clear majority. For this reason, advocates of the Constitution sought the support of the city dwellers, whose delegates, invited to Warsaw from the whole Commonwealth, were expected to strengthen the hand of reformers by their presence. The city dwellers were not informed about the constitutional project or the forthcoming debates and had been ordered to send their delegates to Warsaw only to express gratitude for the April 18, 1791 City Act, which was expressly included in the draft of the May Third Constitution “without any changes.”

In the Sejm hall, twenty-seven deputies, nobles and boyars, openly expressed their opposition to the Constitution. According to the calculations of historian Adolfas Šapoka, the majority of the deputies from Lithuania present in the Sejm chambers backed the reforms: thirty GDL deputies supported the Constitution, while more than twenty were against it.6 However, the Constitution did not receive the backing of the nobles. GDL Vice Chancellor Chreptavičius, even though he was present in the Sejm’s chambers, remained aloof,7 while Sapiega tried to protest publicly against the document, as the initiators of reform had not informed him of its possible adoption. Hearing the text of the Constitution in the Sejm chamber, he demanded a second reading and proposed that the document be approved only when all the deputies had assembled. Realizing that nothing would be changed, he addressed the Sejm:

I see many provisions in this act which do not conform to my convictions and which I would like to change, but because the time for a final decision has come and seeing that the act is fervently supported by so many deputies and that the king has already sworn to it, by standing apart from them I can see only a divided nation and the doom of the homeland […] The duties I hold in the Sejm could make my opposition harmful; it could be used as pretext, without malice intended, to tear down the work of the confederation that has lasted almost three years and is supported by the nation. Foreign forces could take advantage of the division […] Fearing this terrible scene and realizing that in avoiding a small evil I could be bringing about a larger one, for the love of the homeland and its welfare I am, this one time, forced to sacrifice my convictions. I am not self-centered enough to believe that for the sake of the homeland my convictions should be to put into practice rather than those of the king, the honorable Marshall of Poland’s Confederation [Stanisław Małachowski] and the distinguished members of the Sejm. Valuing their virtues, I support the oath given by the king in the Sejm.8

Sapiega’s speech calmed down the inflamed passions. However, historians disagree as to how Sapiega himself should be evaluated. For some, he is an example of personal and political calculation; others argue that the May 3rd speech reflected his genuine sympathies for the reformers of the Patriot Party, which he is said to have concealed because of family ties (through his mother) to the Branickis family, open adversaries of reforms. Sapiega’s subsequent life and adherence to principle on essential questions lend support to the second version.9 Perhaps it would be best to see his speech as an attempt to find a compromise for the sake of the future and the common purposes of the Commonwealth of Two Nations.

Innovations brought about by the May Third Constitution

The May Third Constitution abolished all deleterious laws (and traditions) that raised turmoil in the state and offered opportunities for foreign countries to interfere in its internal affairs. It declared for all times the abolishment of the right of the liberum veto and banned all manner of confederations that disrupted society and undermined its governance or acted in a spirit “contradicting the spirit of the Constitution.” A provision was introduced establishing a hereditary throne, based on the arguments of “the misfortunes experienced during the years without a king,” the duty to protect the state’s inhabitants from disorder, the intent “to block the way for foreign influences for all time,” the necessity of efforts to have authorities “act together for the freedom of the nation, and finally, “in the name of the Homeland.” These reforms were directed against the disregard for political authority that had taken root among the noblemen of the Commonwealth. Furthermore, the small boyars, whose only source of livelihood was all-out service to the nobility, were kept from participating in the political life of the country by taking away their right to vote in the Sejmiks (local parliaments).10 The votes of the small, landless boyars were especially important to the nobles who sought to advance their personal political interests. These restrictions were seen not only as a way to curb license, but excessive freedom as well.

Because of these provisions, the prerogatives of the boyars and the very conception of boyardom changed gradually, conditioned by political as well as mental processes. Some thirty years earlier, a Sejm law had tied the exceptional prerogatives of the boyar to his origin, stating that “in this nation, the boyar right of equality and origin, even of the most impoverished [boyar], is an honor.”11 But in the May Third Constitution, boyardom is said to derive not only from one’s origin, but, in accordance with Enlightenment views, from one’s wealth and responsibilities as well:

We recognize all boyars to be mutually equal, not only in seeking office and serving the homeland, which brings honor, glory, and advantages, but also in access to privileges and prerogatives of the boyar class, first of all, the right to personal security and personal freedom as well as ownership of land and movable property.

In so defining the prerogatives of the land-owning boyars, the Constitution changed the older, archaic model, which limited boyar activities to defense and state government. It also affirmed the 1775 law that allowed the boyars to engage in commerce as well as legalized nobilization, thus opening the boyar class to non-noble persons of distinction. The first article (point eleven) of the City Law of the Constitution declared:

[...] for noble boyars and citizens of the city dweller class on whom later the honor of becoming boyars will be bestowed, from now on there will be no obstacles to accepting the city’s citizenship, to be a citizen, to hold office, and engage in any kind of commerce or maintain any manufactories; this will not adversely affect the honor of the boyars or that of their heirs or the prerogatives tied to it.

The authors of the Constitution ensured for the boyars the exceptional right to property and personal security:

We honor, conserve, and strengthen personal security and any kind of property held legally as a genuine connection in society; they are as precious for the citizens’ freedom as the pupil of the eye; and we want that in the future they be honored, conserved, and inviolable.

But the City Law, part of the Constitution, also ensured the right to property and personal security for city dwellers, who previously did not have these rights. Section III of the Constitution states that the prerogatives granted by the City Law provide “a new and effective power to free boyars for the security of their freedom and the integrity of their common homeland.” One can thus argue that the statement contained in the Constitution to the effect that “all citizens are defenders of the nation’s integrity and freedoms” applies not only to the boyars, but the city dwellers as well. Jokūbas Sidorovičius, a scribe of the Vilnius Magistrate, wrote that the City Law and the May Third Constitution “raised the inhabitants of the city dweller class and merged them into the body of the Commonwealth of Two Nations.” It granted them “a citizen’s life, giving birth to us for the sake of the homeland in which until then we had in fact not lived.”12 This conception of civic life applied to city dwellers, not by virtue of a specific passage in the Constitution, but because their rights and liberties were seen as being equal in part to those of the boyars, and thus included the possibility of holding office at the lower levels of state administration. In other words, city dwellers acquired their rights by virtue of the entirety of the City Law.13 This change reflected not so much a revolution, but rather a cautious modification of the situation existing before the Four-Year Sejm. Cities and their inhabitants were becoming more open, more willing to look beyond their town, more conscious of events in the Commonwealth. The conception of the state and the citizen had begun to change,14 to include not only the boyars, but also the city dwellers and the peasants. A passage in the Constitution about matters related to the defense of the state reflects this fact:

all citizens are defenders of the nation, one and indivisible, and of its liberties. The army is nothing other than the concentrated power of defense arising from the power of the whole nation.

Interestingly, one also finds in the Constitution a formulation describing the peasant class as “[comprising] the greatest part of the nation’s inhabitants and thus its strongest power.”

The May Third Constitution did not complete its task of instituting social reforms; it only opened the way for them. Because the model of the state stipulated in the document was a constitutional monarchy based on class, free peasants were given a separate section. As for persons of Jewish origin, who constituted a separate social group, separate statutes defining their rights and liberties were also being prepared. Occasionally, there are reproaches that the May Third Constitution did not free peasants and did not abolish serfdom. However, one needs to keep in mind that such changes were not feasible because of the growing external threat and the fact that they would have provoked opposition to the reforms as a whole. Discussions about serfdom had appeared in the press, but neither the landowning boyars nor the peasants were prepared for such a change. The authors of the Constitution guaranteed the free peasants only state guardianship and protection under the law in cases of unsubstantiated actions or demands by the landowners.

The May Third Constitution drew up plans for the modernization of the state; however, their implementation required additional laws, decrees, and statutes to regulate the function, structure, internal organization, and activities of existing institutions and of those yet to be created. The head of the central executive power, the actual government, known as the Guardian of the Laws, received the greatest attention in the text of the Constitution. It was forbidden to issue and interpret laws, which indicates that the activities of this institution were determined in a manner that attests to the strict separation of the legislative, executive, and legal authorities. Guidelines for the activities of the three authorities were briefly drawn up in a separate section of the Constitution; however, discussion, debates, preparation, and coordination of various related projects continued to preoccupy the Sejm. With the approval of separate judicial hierarchical structures for the cities, foundations were laid for the creation of separate administrative units, i.e., districts within the state. To assist the Guardian of the Laws, the authors of the Constitution drew up plans for shared commissions of Education, Police, War, and Treasury, even though this was not expressly stipulated in the Constitution. This blueprint for organizing the government was implemented only after the Sejm approved specific laws regulating the structure and activities of the commissions. But there were exceptions.15 Seeking greater effectiveness for the Police Commission, a system of administrative suboffices went into effect toward the end of the Four-Year Sejm. However, on the whole, the formulations of the Constitution were of a more general nature, which left open the possibility of correcting or reinterpreting them as the situation changed. Thus, if the Constitution opened the way and signaled the start of large-scale reforms, it did not have the time to implement them because of increasing tensions and direct threats from the Russian Empire. The Constitution was in force for only one year; the City Law, considered part of it, was briefly reinstated at the time of the uprising of 1794.

The Status of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Commonwealth of Two Nations

The authors of the May Third Constitution tied the strengthening of the Commonwealth to the vision of a centralized and unified country; therefore, the question of the statehood of the GDL within the Commonwealth was not raised, or was circumvented. The nobles and the boyars of the GDL defended the principle of a separate and self-governing state; to them this was a matter of maintaining social prestige and of access to titles and functions that provided greater possibilities for political activities. Thus, it is no surprise that the text of the May Third Constitution was met with dissatisfaction by Lithuania’s deputies. They separated into two groups. The first, led by Sapiega, was inclined to accept a compromise; he swore allegiance to the Constitution, but also strove to restore the rights of the GDL by urging adoption of an additional law to determine questions of the systemic relationship between the two states. The second group, one of whose leaders was Livonian Bishop Juozapas Kazimieras Kosakovskis, was not inclined to enter into any compromises with the reformers; it openly objected, not only to the violations of the rights of the GDL, but also to the restrictions placed on all boyar rights and liberties. 16 This group was the more vocal in the May Third Sejm. As Šapoka recognized, on May 3-5, 1791 the deputies of the GDL in the opposition must have noticed not so much “the unitary nature of the Constitution, but the limitation of boyar liberties and the strengthening of the king’s authority.” He stressed that “the arguments of the Lithuanian deputies who opposed the onstitution were identical to those of the Poles”17 and that, therefore, on May 3rd, the question of Lithuania’s self-government was not uppermost in the minds of the most ardent opponents of reforms. Jūratė Kiaupienė reiterates this idea:

Opposition to the centralization of the Commonwealth (circumventing GDL rights within a common state) was expressed in the Sejm immediately after the adoption of the Constitution in May.19 Therefore, as early as October 20, 1791, the Sejm took up the discussion of a law on the Mutual Guarantee of the Two Nations20 initiated by Sapiega and his supporters. The law was to restore GDL positions as stipulated in the statutes of the 1569 Union of Lublin. When Poland’s nobles and boyars expressed dissatisfaction with the proposed law, Stanisław August, one of the proponents of state centralization and unification, calmed down the Polish deputies and sought a compromise. The compromise did not mean the return of full rights to the GDL; nevertheless, the law adopted included guarantees of equal representation in joint-state institutions (e.g., the War and the Treasury Commissions) for GDL nobles and boyars and for the Polish representatives. The Treasury of the GDL was to remain in Lithuania. However, such a compromise did not fully satisfy those Lithuanian deputies who were generally opposed to reforms.21

It is perfectly clear that the Four-Year Sejm moved in the direction of centralizing the state and its laws, and that the initiators of reforms saw a different Lithuania and a different Poland. The most important common institutions of Poland and Lithuania preserved the appellation “Two Nations,” which meant that the boyars of both countries were to participate in the governance of the joint state. The GDL maintained its status as a political, territorial, and legal subject; the Constitution “confirmed, ensured, and recognized as inviolable the laws, statutes, and privileges” of the land-ruling boyars. Clearly, the Third Statute of Lithuania was also maintained, as were the others, even though the Constitution provided that “persons [be] appointed by the Sejm to compose a new code of civil and criminal laws.” One must also understand that the provisions of the Constitution did not all go into effect; new laws revised some of them.

Research by Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė has shown that the majority of GDL boyars supported the reforms of the Four-Year Sejm and remained faithful to its statutes until the moment when Stanisław August, believing that the Commonwealth would not be able to withstand threats and pressures from Russia, agreed to its demands and swore allegiance to the Targowica Confederation.22 It is important to remember that reactions provoked by the Targowica Confederation (and later the GDL General Confederation, created at the time of the Russian intervention) offered an excellent excuse for Russia to invade the Commonwealth, and that the support of the antireformers in Lithuanian society was not the issue. Politicians of the Russian Empire were interested neither in the status of the GDL within the Commonwealth nor the preservation of “the golden liberties.” These matters were no more than levers for undoing the unity of the boyars of Poland and Lithuania on the principal question of the state’s existence. Politicians of the Russian Empire used them successfully to their advantage.

The idea of the GDL was strong among supporters of reform and in no way limited to their opponents. On June 19, 1792, scores of Lithuania’s boyars who had withdrawn to Grodno sent a signed proclamation to Warsaw as a sign of their fidelity to the reforms of the Four-Year Sejm. The proclamation began with the words “We, citizens of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania” and ends with an oath:

In the eyes of God, Homeland, and the world […] we declare that we will not withdraw or abandon the [ideas] of self-government of the Republic, the cause of public and private liberties, the May 3rd and the May 5th Government Law and the laws passed by virtue of that law.23

One of the signers of the proclamation bore the same name as the more famous Treasurer of the GDL Palace, Antanas Tyzenhauzas (Antoni Tyzenhauz), and was his distant relative. Family ties with an important official of the GDL helped Tyzenhauzas, the signatory, seek a career (from 1776 as a messenger to the Sejm, from 1778 as standard-bearer of Vilnius) and gain access to Stanisław August, who later on his own favored and supported Tyzenhauzas. The latter began his career as an officer in the Grodno battalion and later served in the regiment of the GDL Guard, earning the rank of colonel. His activities reached their high point at the time of the Four-Year Sejm and the 1794 revolt: in 1790, he was elected messenger to the Sejm by the Sejmik of the Vilnius voivodeship. The next year, he was the first to accept the rights of a city dweller and swear allegiance to the City Law. The king may have had great hopes for him from the beginning of the city reforms and intended to appoint him to a post in the government of the city of Vilnius. In any case, on April 14, 1792, Tyzenhauzas was unanimously elected senior official (president) of Vilnius. He withdrew to Grodno and the interior of the Commonwealth when the Russian army invaded the city, returning to Vilnius after the king took an oath to support the Targowica Confederation. He followed the king’s example, as did many other supporters of the Constitution. Tyzenhauzas was relieved of his duties as president of the city when the GDL General Confederation abolished reforms instituted by the Four-Year Sejm.

In 1793, Tyzenhauzas began participating in the activities of a secret group in Vilnius. He joined the Council of Lithuania’s Supreme Government the following year, at the start of the 1794 uprising, regained his position of city president, and headed several commissions (including the Provision Deputation and the Secret Deputation for Order). He was one of the authors of the Vilnius Revolt Act, which proclaimed the start of the uprising in all of Lithuania. Tadas Kosciuška (Tadeusz Kościuszko) and Hugo Kołłątaj did not like the contents of the proclamation and appealed to Jokūbas Jasinskis, demanding that he, along with Tyzenhauzas, correct it to include that, with the Vilnius act, the “Province of Lithuania” was joining the revolt that had begun near Kraków.24 The President of Warsaw City, Ignacy Zakrzewski, dissatisfied with the contents of the Vilnius Revolt Act, also sent Tyzenhauzas a letter, expressing his concern that Lithuanians were striving to establish a separate leadership from Poland. Tyzenhauzas replied that the goals of the Vilnius act did not essentially differ from the Kraków act except for the fact that the Kraków act was the first act of one voivodeship, which “the other voivodeships of [Poland’s] kingdom had to follow, while the act of Lithuania’s [revolt] had become a common act for all of Lithuania.”25 This means that Tyzenhauzas, even though he belonged to the king’s political group, was one of the most active organizers and leaders of the revolt in Lithuania, guided by the GDL traditions of self-government and the continuity of the state. He clearly recognized the GDL as distinct from the Kingdom of Poland.

The evolution of historians’ evaluations

Two scholars of the eighteenth century, Ramunė Šmigelskytė- Stukienė and Robertas Jurgaitis, represent different camps in evaluating the significance of the May Third Constitution, but they agree that the essential question concerns the following: to whom does the historical document belong, Poland alone, or both Poland and Lithuania? Is it only significant for Poland or for Lithuania as well?26 The thesis that the name Lithuania does not exist in the document and that the joint state is referred to as Poland continues to carry weight. That is why the question of the self-government and the statehood of the GDL is the most important issue in current debates, frequently overwhelming other issues.

Some historians of Lithuania have claimed that in the text of the May Third Constitution the Commonwealth of Two Nations is called Poland; this has been perhaps the main argument for saying that the Constitution is alien to Lithuania. However, in the text of the Constitution, the joint state of Lithuania and Poland is named in various ways: “Poland,” “lands of Poland,” “Republic,” “states of the Republic,” and “common Homeland.” It has also been claimed that the name of Lithuania does not appear in the text of the document at all, but in fact Lithuania is mentioned in several places. Some scholars remain apprehensive and say that the Constitution refers to the two political entities, the Poles and the Lithuanians, as one “nation,” or simply “the Polish nation,” but in fact, in some instances, the boyars of Lithuania identify themselves with the GDL and in others with the Commonwealth. These tendencies surface as early as the seventeenth century. There are painful reactions to the fact that the GDL is ever less frequently called a state and ever more often one meets the name of the GDL as province. The Polish historian Grzegorz Blaszczyk stressed that “Lithuania was a province of the Republic, of the joint state of Poland and Lithuania, but it was not a province of Poland.”27 It is also important to direct one’s attention to the fact that in the Commonwealth of Two Nations other provinces, for instance Greater or Lesser Poland, did not have the same political rights as the GDL. Moreover, unlike the GDL, they were not called states.

But how did such a negative perspective arise, leading to that one question to be debated? The first historian in whose writings the question of the GDL’s self-governance (during the reforms of the second half of the eighteenth century) arose is Šapoka. Relying on his assertions, some historians treat the May Third Constitution as a law that tramples on, or abolishes entirely, the statehood of Lithuania. This view was especially popular in Lithuania in the second half of the twentieth century. The main arguments proposed were as follows: in the Constitution, the rights of the GDL and those of the Kingdom of Poland are made uniform; the name of Lithuania does not exist in the document; the document mentions only one nation (as it were eliminating the nation of Lithuanian boyars), with a common government and a common monarchy. These arguments seem to blind historians, and they fail to see the Constitution’s positive tendencies in the sociopolitical area. For instance, Vanda Daugirdaitė-Sruogienė mentions the May Third Constitution in her Lietuvos istorija (History of Lithuania) only to say that, as she sees it, Lithuania was destined “to become a province of Poland. Such was the famous May Third Constitution. It’s just that this ruinous plan for Lithuania was not implemented.”28

But Šapoka’s attitude toward the May Third Constitution evolved from a rather severe to a more moderate one.29 In his 1936 Lietuvos istorija, Šapoka explains that, in order to strengthen the Commonwealth and increase its international importance, “not only the boyars, but also other segments of the joint state had to give up a great deal. Because of efforts to centralize everything, the self-governing mechanisms of the state of Lithuania were being dismantled. […] In this way, the Four-Year Sejm tried to end the union and finally blend Lithuania with Poland into a single state.”30 In the 1938 Lietuva ir Lenkija po 1569 metų unijos (Lithuania and Poland After the 1569 Union) Šapoka stressed the fact that in the text of the Constitution the question of Lithuania’s organization remained unclear, adding that all the obscurities:

had to be resolved by separate laws in debates about them, the road for Lithuania to defend its rights remained open. She could still wrest at least as much separateness as she had at the time when the Permanent Council was in force. The Constitution did not block the path for self-governing mechanisms in Lithuania, her expressis verbis was not denied, but it was silenced, seemingly ignored. Of course, it was ignored consciously because the main idea of the authors of the Constitution was to create a firm and unified government for the whole Republic.31

Two years later, in the 1940 monograph Gegužės 3 d. konstitucija ir Lietuva (The May Third Constitution and Lithuania), Šapoka wrote:

Dreaming about the abolishment of the separate state organization as well as the creation of a strong central authority, the authors of the Constitution tried not to write even a single word that could have been any kind of support for Lithuanians who defended the traditions of their separate life. However, apparently seeking to avoid arousing the Lithuanians, they also did not write a single word by which the state organization of Lithuania could be dismantled. Therefore, the path to demand later the preservation of the old relations was not blocked for the representatives of Lithuania.

That, according to the historian, led to the appearance of Abiejų Tautų savitarpio garantijos įstatymo (Law on the Mutual Guarantee of the Two Nations).32 To restate Šapoka’s positions, in 1936 he wrote that the “independent organization of the state of Lithuania was being dismantled” by the Four-Year Sejm; in 1938, he softened his position, explaining that “[The May Third] Constitution did not block the road for an independent organization of Lithuania”; and in 1940, he stated that the Constitution contained not a single word “by which the state organization of Lithuania could be dismantled.” Surely, these later theses were influenced by Šapoka’s reading of the Law on the Mutual Guarantee of the Two Nations. However, the earlier judgments proposed by Lithuania’s first professional historians remained the better known and heard.

Twenty years ago, articles by Juliusz Bardach and Leonas Mulevičius33 resurrected discussions about the Law on Mutual Guarantee of the Two Nations adopted by the Sejm on October 20, 1791. Historians of Lithuania who came after Šapoka did not mention the law for about half a century. Bardach and Mulevičius agreed that the law legalized a two-member Republic and preserved the rights of Lithuania as a subject of the union. However, even after Bardach and Mulevičius, the May Third Constitution was often viewed primarily as a Polish conspiracy against Lithuania. Bronius Makauskas wrote in his Lietuvos istorija (A History of Lithuania):

The purpose of the May Third Constitution was to consolidate the centralized authorities in Lithuania and Poland and merge them finally into one state. However, there was resistance on the part of the Lithuanians, and we have to say that an honorable and not so bad compromise was found [the Mutual Guarantee of the Two Nations] by the reform camp of the Four-Year Sejm.34

One can see clear changes in recent interpretations and evaluations. In 2001, Mečislovas Jučas explained that the Constitution remained silent on the question of Lithuania’s status and the two states’ union; that it undermined the notion of a joint state divided into a kingdom and a duchy; and that Lithuania’s name had not remained in the Constitution. He also stated that the October 20, 1791 Law on the Mutual Guarantee of the Two Nations, adopted on the initiative of the Lithuanians, could not “change the main directions of the May Third Constitution,” which lead to the unification of the state.35 But ten years later, in Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės istorijoja (History of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania), Jučas was more careful, more inclined to emphasize the significance of the Mutual Guarantee of the Two Nations:

In the Constitution the union was not mentioned, but it was not abolished […] The main laws of the Four-Year Sejm relied on the act of the Lublin Union. The Constitution itself did not dismantle the union. Although its authors went in the direction of centralizing state authorities and nominated common commissions for the entire state, in the commissions themselves the set proportion of representatives left to Lithuania remained unchanged.36

Seeking alternatives for the May Third Constitution

Because the May Third Constitution was understood as a document that undermined Lithuania’s self-government within the joint state with Poland, efforts were made to find significant (positive) alternatives. It was Šapoka who laid the foundation for this perspective, explaining as early as 1936 that the Targowica Confederation, although it opposed the reforms of the Four-Year Sejm and spoke in favor of the old order, “reinstated the old distinctness of the states of Lithuania and Poland.”37 The very first lines of the GDL General Confederation Act declare as follows:

We, citizens and boyars of the Lithuanian nation, associated with the Crown of Poland, having the same prerogatives of privilege and rule, national duties, and jurisdictions in our own land represented by our own citizens, being a nation equal in might and significance to the Kingdom of Poland […].”38

Valdas Rakutis disagreed with Šapoka, explaining that the historian was formulating a thesis out of touch with reality. He pointed out that the confederationists did not have their own army and relied on the military forces of the Russian Empire. He therefore proposed that they should be regarded as Russia’s protégés and that, for that very same reason, the 1792 war was not a civil war: “some defended the homeland, others betrayed it.”39 But Vydas Dolinskas, who recognized the confederationists’ efforts to maintain Lithuania’s statehood, in essence backed Šapoka’s line of argument, while at the same time disagreeing in part with his evaluation. He saw as unethical the many twists and turns in the career of the GDL Confederation leader Kosakovskis (such as taking advantage of the enemy’s intervention, usurping the post of hetman, engaging in financial manipulations, appropriating state estates, persecuting political opponents) and held that whatever one’s evaluation of Kosakovskis, Lithuanian historiography faced a dilemma, for as early as the Bar Confederation Kosakovskis and his group “defended the traditional state status granted the Grand Duchy of Lithuania within the legal and administrative systems of the Commonwealth of Two Nations.”40 Despite this evidence, the reaction of the most conservative boyars to the reforms of the Four-Year Sejm as well as their reliance on a foreign army to realize their political goals are for the most part evaluated unfavorably by Lithuanian historians or taken as “a symbol of the state’s downfall.”41

In public discussions, the resolutions of the 1793 Grodno Sejm are sometimes viewed as an alternative that, more so than the May Third Constitution, favored processes that advanced Lithuania’s statehood. They are said to have provided a much firmer and better defined foundation for the GDL’s status within the Commonwealth than was the case at the time of the Four- Year Sejm. The provisions of the Grodno Sejm strengthened the status of Vilnius, to which many of the most important state institutions were transferred; they created commissions of War, Treasury, and the Police for the GDL separately from those of the Kingdom of Poland. One must emphasize that, in the historiography of both Poland and Lithuania, the resolutions of the Grodno Sejm are often assessed incorrectly as having consolidated the situation that existed before the Four-Year Sejm. Historians give too much emphasis to a law that declared the Sejm laws of the Four-Year “revolutionary sejm” invalid and abolished.42 However, if one looks at the totality of the decisions of the Grodno Sejm, one understands that it adopted most of the provisions of the Four-Year Sejm, with certain modifications. Additional research into the goals and activities of the Grodno Sejm is certainly needed.43 Unfortunately, to date, this topic has not been popular among historians, perhaps because the Sejm legalized the Second Partition of the Commonwealth, decreasing the size of the armies of Poland and Lithuania. Its decisions held for only four months, until 1794, and were abolished when the rebels took over the government. Nevertheless, at the very end of its activities, the Grodno Sejm took decisions that in no way conformed to those of the Targowica and the General Confederation or constituted a continuation of reactions against reforms. It was a reform-minded Sejm, and it tried to win as many concessions as possible from the Russian side. Suffice it to mention that Catherine II became angry with one of her officials (Jacob Johann Sievers) who failed to block the decisions of the Grodno Sejm and recalled him from the Commonwealth. 44 One might add that, on the second-to-last day of its session, the Sejm adopted a law that allowed the wearing of military decorations earned in the Commonwealth’s 1792 war with Russia, explaining that these decorations “demonstrated one’s fighting spirit and encouraged such courage.”45 The wearing of the decorations had been forbidden by the confederationists.

General Conclusions

The May Third Constitution is an extraordinarily significant document in Lithuania’s history, not just because one can be proud of it as one of the first constitutions in Europe and the world, but also because it proved that the Commonwealth of Two Nations was not the backward and hopeless state it was portrayed to be after its liquidation. The state and its society made great efforts to institute reforms, move forward, and escape from political isolation. The last years of the Commonwealth’s existence demonstrate that the course of reforms adopted by the Four-Year Sejm was carried forward by the Grodno Sejm in 1793 and the revolt of 1794. The May Third Constitution also gives evidence that the collapse of the state was determined, not by internal disorders, but rather the imperialistic aims of neighboring states. In evaluating the Constitution, one probably ought to take a broader look, instead of confining oneself to historical Lithuania or the situation in 1791.

I believe that one of the essential problems in the debate about the May Third Constitution remains the painful historical experience of the twentieth century. Scholars should try to free themselves from it, keeping in mind that the idea of modern Lithuania did not exist in 1791. There existed a different Lithuania at that time, and Poland was likewise different. The contrast of Poland with Lithuania was not the axis of the existence of the Commonwealth, even though it became fundamental in twentieth-century textbooks of Lithuanian history. To move forward in the discussion, one has to cast one’s net widely and look at the political, social, and civic changes that mark the last years of the GDL. Answers will not be simple; no doubt they will be more complicated than we imagine them today.

In conclusion, I must stress that a different point of view than the one argued in this article is not necessarily defective. One can debate both perspectives. Today the fundamental disagreements stem from the way one understands the question: what do I consider mine and what foreign? One has to keep in mind that, in 1902, Jonas Mačiulis-Maironis was the first to cross the threshold into the Lublin Union, making the Commonwealth of Two Nations part of Lithuania’s history. Even though there were doubts for a long time about the significance of the 1863-1864 revolt for Lithuania’s history, 46 today the matter is settled, and the upcoming year 2013 has been proclaimed as the year to remember the revolt of 1863-1864. But I acknowledge that one of the most important issues in discussions about the May Third Constitution is the difficult question of the hierarchy of its meanings and symbols. For that very reason it may not yet be time for political decisions: to commemorate the May Third Constitution or not?

WORKS CITED

Aleksandravičius, Egidijus, et al. Praeities

pėdsakais. Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas, 2007.

Bardach, Janusz. “Konstytucja 3 maja a ‚Zaręczenie obojga narodów’ 1791 roku,” Studia juridica, Vol. 24, 1992.

Blaszczyk,

Grzegorz. “Współczesne spojrzenie na stosunki

polskolitewskie w latach 1569-1795,” Rzeczpospolita w XVI-XVIII

wieku. Państwo czy wspólnota? Ed. B. Dybaś, et

al. Toruń: Wydawnictwo naukowe uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, 2007.

Bohusz,

K., “Spominka o Antonim Tyzenhausie,” Tygodnik wileński,

1820, No. 161.

Burbaitė,

Eglė, Deimantas Karvelis, Rūta Ringytė. “Dar kartą apie

Gegužės 3-osios konstituciją,” Istorija. Mokslo darbai,

Vol. 72 and “Dar kartą apie Gegužės 3 dienos konstituciją:

komentaras kronikai,” Istorija.

Mokslo darbai, Vol. 75.

Brusokas, Eduardas, et al. “Biurokratinių struktūrų raida Lietuvos Didžiojoje Kunigaikštystėje 1775-1795.” Research financed by the Research Council of Lithuania (Contract no. MIP-03/2010).

_____ and Liudas Glemža, “Vilniaus savivaldos struktūra ir organizacija po Ketverių metų seimo miestų reformos (1792, 1794),” Lietuvos istorijos metraštis, 2008, Vol. I, Vilnius, 2009.

Daugirdaitė-Sruogienė,

Vanda. Lietuvos istorija.

Vilnius: Vyturys, 1990.

Dolinskas,

Vydas.

“Paskutinis Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės

didysis

etmonas Simonas Kosakovskis: Biografija ir bandymas įvertinti

karjerą,” Chronicon

palatii Magnorum Ducum Lithuaniae. Vilnius, 2011.

_____.

Simonas Kosakovskis:

politinė ir karinė veikla Lietuvos Didžiojoje Kunigaikštystėje,

1763-1764. Vilnius: Vaga, 2003.

Glemža,

Liudas. Lietuvos

Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės miestų sąjūdis 1789- 1791 metais.

Kaunas: Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas, 2010.

Jučas,

Mečislovas. Lietuvos

Didžioji Kunigaikštystė. Istorijos bruožai.

Vilnius: Nacionalinis muziejus, LDK Valdovų rūmai, 2010.

Jurgaitis, Robertas, and Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė. “Ketverių metų seimo epocha Adolfo Šapokos tyrimuose,” in: Adolfas Šapoka, Lietuva reformų seimo metu. Raštai II. Vilnius: Vilniaus pedagoginio universiteto leidykla, 2008.

Kiaupa,

Zigmantas, Jūratė Kiaupienė, Albinas Kuncevičius. Lietuvos istorija iki 1795 metų.

Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas, 1995.

Kądziela,

Łukasz. “Sapieha Kazimierz Nestor h. Lis (1757 –

1798),” Polski

słownik biograficzny, Vol. XXXV/1, No. 144,

Warszawa-Kraków, 1994.

Lopata,

Raimundas, and Vladas Sirutavičius. Lenkiškasis istorijos

veiksnys Lietuvos polikoje. Vilnius: Vilniaus

universitetas, 2011.

Makauskas,

Bronius. Lietuvos

istorija. Kaunas: Šviesa, 2000.

Mościcki,

Henryk. General

Jasiński i powstanie kósciuszkowskie. Warszawa,

1917.

Mulevičius,

Leonas. “Lietuvos savarankiškumas ir Abiejų Tautų

savitarpio garantijos įstatymas,” Lituanistica, 1992,

No. 4 (12), 1993.

Raila, Eligijus, ed., tr., and V. Čepaitis, ed. 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucija ir Lietuva. Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademija, 2001.

Rakutis,

Valdas. LDK kariuomenė

Ketverių metų seimo laikotarpiu (1788-1792). Vilnius:

Vaga, 2001.

Staliūnas,

Darius. Savas ar svetimas paveldas? 1863-1864 m. sukilimas kaip

lietuvių atminties vieta. Vilnius: Mintis, 2008.

Sidorowicz, Jakub. “Mowa przy przyjęciu obywatelstwa miasta

Wilna przez K. N. Sapiehę,” in Materiały do dziejów

Sejmu Czteroletniego, eds. Janusz Woliński et al. Vol. 4.

Wrocław, Warszawa – Kraków, 1961.

Sirutavičius,

Vladas. “Lenkijos elitas nėra prorusiškas, jis

– prolenkiškas,” online: http://www.delfi.lt/news/daily/lithuania/vsirutavicius-lenkijos-elitas-nera-prorusiskas,

jis – prolenkiskas.d?id=53206151.

Szyndler,

Bartłomiej. Powstanie

kościuszkowskie 1794. Warszawa:Ancher, 1994.

Šapoka,

Adolfas. 1791 m.

gegužės 3 d. konstitucija ir Lietuva. Eds. Eligijus Raila

and V. Čepaitis. Kaunas: Vilniaus dailės akademija, 2001.

_____.

Lietuva ir Lenkija po

1569 metų Liublino unijos. Kaunas: Švietimo

ministerija, 1938.

_____. Lietuva reformų seimo metu.

Iki 1791 m. Gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos. Raštai II. Eds.

Jurgaitis and Šmigelskytė-Stukienė. Vilnius:

Vilniaus

pedagoginio universiteto leidykla, 2008.

_____,

ed. Lietuvos istorija.

Kaunas: Švietimo ministerija, 1936.

Šmigelskytė-Stukienė,

Ramunė. “Geopolitinė situacija Europoje ir Lenkijos-Lietuvos

valstybės padalijimai,” in Lenkijos-Lietuvos valstybės

padalijimų dokumentai, Part I: Sankt Peterburgo

konvencijos. Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas, 2008.

_____.

“1792 Kauno pavieto konfederacija,” Kauno istorijos

metraštis. Kaunas: Vytauto Didžiojo

universitetas, 2004.

_____.

“Kauno pavieto bajorija valstybės permainų

laikotarpiu,” Praeities

pėdsakais, Vilnius, 2007.

_____.

Lietuvos Didžiosios

Kunigaikštystės konfederacijos susidarymas ir veikla

1792-1793 metais. Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas,

2003.

_____.

“Už ar

prieš reformas: Ketverių metų seimo nutarimų įgyvendinimas

Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės pavietuose

1789-1792 metais,” Istorija,

Vol. 74, No. 2, 2009.

Tracki,

Krysztof. Ostatni

kanclerz litewski Joachim Litawor Chreptowicz w okresie Sejmu

Czteroletniego. 1785-1792. Wilno: Czas, 2007.

Tumelis, Juozas. “Gegužės trečiosios konstitucijos ir Ketverių metų seimo nutarimo lietuviškasis vertimas,” Lietuvos istorijos metraštis. Vilnius: Mokslas, 1978.

“Warunek prerogatyw stanu szlacheckiego,” in Volumina legum, Vol. 7.

Volumina legum,

Vol. 7, ab anno 1764 ad

annum 1769. Petersburg: Ohryzki, 1860.

Volumina legum,

Vol. 9, ab anno 1782 ad

annum 1792. Kraków: Wydawnictwo komisji

prawniczej akademii umiejętnosci w Krakowie, 1889.

Volumina legum,

Vol. X, Konstytucje

sejmu grodzieńskiego z 1793 roku.

Poznań : Nakładem Poznańskiego towarzystwa przyjaciół nauk z

zasiłkiem ministerstwa szkolnictwa wyzszego i Polskiej akademii nauk,

1952.

Zytkowicz, Leonid. Rządy Repnina na Litwie w latach 1794-7. Wilno: Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk, 1938.