Copyright © 2013 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Editor of this issue: Jurgita Staniškytė

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2013 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 59, No.1 - Spring 2013

Editor of this issue: Jurgita Staniškytė |

Kaunas Architecture in Wood

NIJOLĖ LUKŠIONYTĖ

NIJOLĖ LUKŠIONYTĖ is a professor at the Faculty of Arts at Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas. Her research interests include the history of Lithuanian architecture of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and the theory and practice of preserving and protecting Lithuanias built cultural heritage.

Abstract

This article reveals the diversity of wooden architecture in Kaunas

and describes its cultural value. Historic wooden buildings, such

as small manor and garden estate houses, villas, cottages, summer

homes, rental houses, and military and railway complexes,

have survived in all parts of Kaunas. Such buildings are exceptional

at conveying a local identity. A large number of the houses

are neglected and deteriorated, while others have been renovated

in a manner that compromises their original style and substance.

Consequently, it is very important to distribute documentation

on old timber houses in order to motivate their owners to restore

them correctly. In 2011, a database of Kaunass wooden architecture

(HTTP://www.archimede.lt)

was begun and continues to be updated

at the Vytautas Magnus University Faculty of Arts. It is hoped that

the information on this website will reach the homeowners as well

as district and municipal administrators, and an appreciation of

the historic and cultural value of wooden architecture will gradually

develop among them all.

Numerous wooden buildings, such as small manor and garden estate houses, villas, cottages, summer homes, residential rental units, and military and railway complexes, have survived in Kaunas. Representative buildings of all the different types need to be preserved in each area, because they are exceptional in conveying local identity. This article aims to reveal the diversity of wooden architecture in Kaunas and to describe the cultural value of these buildings.

Although most wooden houses were built during the first half of the twentieth century, some date to before the end of the nineteenth. Timber is a relatively inexpensive building material, but it is not as durable as brick. Wooden homes deteriorate more quickly and face a greater danger from fire, especially in densely built areas. The oldest surviving wooden buildings are located on the edges of the historic city center and were built by the more affluent residents. The poorer strata of society were concentrated in the southern district of Šančiai and on the right bank of the Neris River, in Vilijampolė Wooden buildings were also built in Žaliakalnis, which is situated on the upper terrace of the city, as well as in Panemunė, an area zoned for recreation. Žaliakalnis was considered a prestigious district, where administrative workers and military officers, intellectuals, and those in the creative arts resided. Unlike other areas of the city, only Lithuanians lived in this district. Houses were built on spacious lots with gardens, and wooden dwellings of many types were built there: traditional garden homes, with and without mezzanines; asymmetric villas; and two-story buildings intended for rental flats. All wooden houses were designed by professional architects or technicians and reviewed by the municipal buildings division in advance of construction.

Wooden houses and features of their construction and style.

Ethnic traditions and professional architectural solutions were so intertwined in the nineteenth century that it is difficult to divide buildings into groups according to their formal architectural style. The buildings in the city generally have no distinct stylistic traits; therefore, they could appropriately be termed local, prior to researching the more definitive tendencies they reflect. The concept of vernacular architecture, as defined by the ICOMOS Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage (1999), applies to this phenomenon as well.

Urban buildings in nineteenth-century Lithuania were constructed from hewn logs, and the external walls were planked with narrow boards placed vertically or horizontally. Roofs were covered with iron or tin sheets. The walls of the houses built during the interwar (1918-1939) period are either of log or timber frame construction, planked, and less decorated on the outside than the buildings constructed at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century.1 The so-called Swiss Style, which was prevalent in other European countries,2 was also part of the decorative design of Kaunas buildings. Sheets of roofing iron or clay tiles protected roofs during the interwar period.

Earliest examples

A look at the plan of Kaunas during the middle of the nineteenth century shows that the historic core of the city consisted of numerous wooden houses. Residences, estate buildings, and outdoor stairways were constructed of wood, and fences were similarly equipped and erected. Unfortunately, only a few wooden buildings from that time have survived in Old Town. For instance, several one-story buildings still stand on M. Valančiaus Street, their rear facades facing the former Fish Market. The vaulted cellars of the wooden building at 9 M. Valančiaus have survived since the sixteenth century. Its structure, consisting of long, rough-hewn logs topped with a jerkinhead roof, was fashioned in the mid-nineteenth century and renovated in 1986. Buildings of this type, with high roofs and windows in six panes flanked by shutters, appeared in the provinces on the smaller estates of boyars.

As per the 1847 plan approved by the administration of Czarist Russia, Old Town was zoned for brick construction, and the construction of wooden residences was no longer permitted. The territory of Naujamiestis (New Town), which was a specific subdivision of streets planned in 1847, had several original farmsteads dating from as far back as the eighteenth century. The best-known was the since demolished Kartofliški Folwark Manor, near the present A. Mickevičiaus Street. Here Stanisław Dobrowolski, the chief officer of schools for the Kaunas Guberniya, commissioned a wooden house with a columned porch, which was completed about 1828. The residence, outbuilding, and wing formed a half-enclosed yard. The walls of the building were raised upon the vaulted half-cellar, with its kitchen and brewery; its jerkinhead roof is shingled in wood. Small manors in the classical style no longer exist in Kaunas. The last one, which stood at 30 Jonavos Street, was demolished a few years ago.

|

| Demolished Kartofliški Folwark Manor (photograph from the collection of V. Chomanskis, around 1925) |

Another small manor is located at 4 K. Būgos Street. Built in 1850 for its owner, Barbora Matuševičienė, it has an elongated rectangular plan capped with a jerkinhead roof. The high foundation is made of stone and the walls are logs clad with boards. The windows, with six panes and shutters, have wide frames reminiscent of classical cornices. During the interwar period, it was remodeled into several rental apartments.

|

| Manor at 4 K. Būgos Street (photo by N. Lukšionytė, 2000) |

Urban residential houses of the end of the nineteenth century

Homes on the regular blocks of Naujamiestis, facing the main streets, were required to be built in brick. Nonetheless, small wooden houses sprang up in the inner areas of the blocks as well as at their edges (currently, K. Donelaičio and V. Putvinskio streets). They also predominated in the Karmelitai neighborhood, between Karo Ligoninės Street and the railway station. Because a home was built in wood did not mean the owner had limited resources to invest; it often simply reflected a preference for a traditionally-built abode. Owners would sometimes erect a two-story brick house along the street for rental purposes, and then build a wooden house in the rear yard for their own residence (such as the one located at 32a Laisvės Avenue). A good number of wooden, single-family homes from the end of the nineteenth and start of the twentieth centuries have survived in Naujamiestis. The asymmetrical ornamentation with a multitude of carvings, which is characteristic of villas, is nearly gone from the 1896 home owned by Aleksandras Makūnas at 43 Kęstučio Street. The largest group of wooden homes still surviving in Naujamiestis is on K. Donelaičio Street. The lots for houses at 7 and 11 belonged to Login Ščerbakov, a subcontractor for the military garrisons Orthodox Cathedral, and later to his son Fadej. The Ščerbakov family, who were members of the Old Believers Russian faith, acquired this land in 1895. The facades are clad with horizontal wooden boards and decorated with carvings reminiscent of crochet work, characteristic of Russian architecture. These carvings cover the foundation of the houses and the fascia and window cornices in several rows. The homes were built and decorated by master woodworkers from the Chernigov Guberniya. Three wooden houses stand next to them at 1, 1a and 5 K. Donelaičio Street. All of them were built around 1860 and belonged to Rudolf Marker toward the end of the nineteenth century. The house at 5 K. Donelaičio (1896) is distinguished by neoclassical forms applied in wood.

|

| Ščerbakov house at 7 K. Donelaičio Street (photo by I. Veliutė, 2009) |

|

| Marker house at 5 K. Donelaičio Street (photo by I. Veliutė, 2009) |

Wooden buildings from Czarist times can still be found everywhere along the edges of the city of Kaunas. A few remain in the Totorių outskirts (between the current streets of Birštono and I. Kanto). The foundation of the house on the corner at 5 D. Poškos Street (1910) is planked with vertical boards, while the walls are covered with horizontal siding. On the gables, the siding is laid out in a fir-tree pattern; an ornate band of pierced work runs under the cornice. The windows have six panes and are equipped with shutters.

The Jewish people who settled along the narrow pathways in Vilijampolė, between Jurbarko, Panerių, and Linkuvos streets, built modest homes containing small shops. The sides of some of them face the street (10, 14 and 47 Jurbarko Street), but the rear of others are towards the street (12, 27, 30, 43 and 52 Jurbarko). Their cottage roofs are covered in tin, and they lack mansards and mezzanines; their doors face the street directly; and the windows have shutters. There is an occasional two-story building earmarked for rentals. Since construction is dense, the arched entrances face into the yards (25a and 49 Jurbarko Street). This does not occur in Žaliakalnis or other neighborhoods of the city.

The outskirts of Žemieji (Lower) Šančiai formed in 1862, when factories were established there. Laborers settled in the area after the railroad had been laid. The little streets that appeared along the shores of the Nemunas River were built up in stages, with wooden cottages on small lots. The earliest sprang up at the beginning of the twentieth century (117 A. Juozapavičiaus Prospect and 77 Kranto Avenue). Many, however, were built during the interwar period. Small, one-story garden cottages were the most widespread in Šančiai; some had open porches or verandas and window shutters (21 Mažeikių Street, 35 and 124 Kranto Avenue, 8 Sodo Street, 12 Kranto 2-oji Street and 18 Kranto 17-oji Street). The occasional home is more decorative, boasting a jerkinhead roof and elaborate carvings, such as those at 86 and 89 Kranto Avenue.

Houses for railway workers and military personnel

It is natural that tracery in the characteristic Russian Style was adapted to the buildings of the military fortress in Kaunas. Large barracks and smaller houses containing flats for officers in the military site in Šančiai (1895-1899) were built of red brick, while the oblong, one-story houses for noncommissioned officers were of wood. Low hip roofs were covered with roofing iron, and the friezes and bases of the walls were covered in carved bands (15, 40 A. Juozapavičiaus Prospect and other locations). Variations of these decorations were typical in military architecture. The military houses in the Freda neighborhood are smaller, and some display Swiss Style motifs (46 Lakūnų Highway). The houses built close to the railway station for railway employees at the end of the nineteenth century display a modified Russian Style decoration. Russian Style carvings and window trim are matched with the projecting molded ends of the rafters and interlocked cross trusses in the gables, characteristic of the Swiss Style (17 Tunelio Street; 124c, 125, 131 A. Juozapavičiaus Prospect).

|

| Railway workers house on A. Juozapavičiaus Prospect (photo by N. Lukšionytė, 2012) |

Quite frequently, wooden buildings with several apartments earmarked for rental units were built. A residential facility for railway workers was erected at 17 Tunelio Street by Gustav Lechel, the supervisor of railway buildings on the St. Petersburg-Warsaw line, in 1897-1899. The elongated symmetrical building was planned for six one-room rental units, with the kitchens having private entrances off the porches, along with two more of the same type of unit on the mezzanine level. The house is generously decorated with Swiss Style elements wide, molded window casings and decorative cornices resembling small shelves over the windows and framing the gables, porches, and verandas. Along what is currently A. Juozapavičiaus Prospect, homes were built for the employees of and laborers on the railway. These were of only one story, but lengthy (sufficient for several apartments), complete with porches decorated with pierced carvings (121 and 125 A. Juozapavičiaus Prospect). Although the buildings are similar to one another, they are not quite the same.

|

| Sergeants house on A. Juozapavičiaus Prospect (photo by I. Veliutė, 2009) |

Between 1895 and 1899, wooden homes for noncommissioned officers in the military zone of Šančiai were built at 15, 30, 32, 36, and 40 A. Juozapavičiaus Prospect. These are identical elongated one-story buildings with metal roofs over the porches, as well as typical decoration.

Wooden public buildings

At the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century, various wooden structures related to entertainment and recreation were built within the urban environment of Kaunas. Unfortunately, with patrons needs and level of comfort changing, they have all been reconstructed or demolished. We only know about these buildings from old photographs.

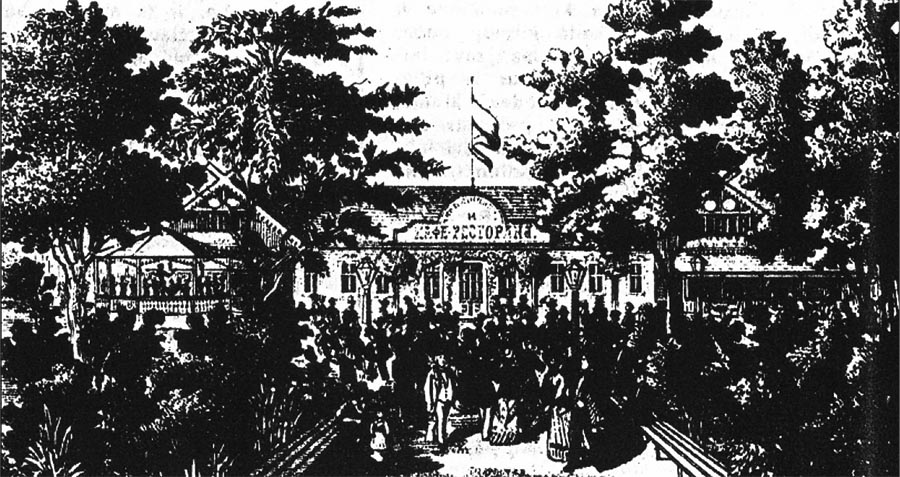

|

| Wooden pavilion in the City Garden (demolished; from Souvenir de Kovno, 1882) |

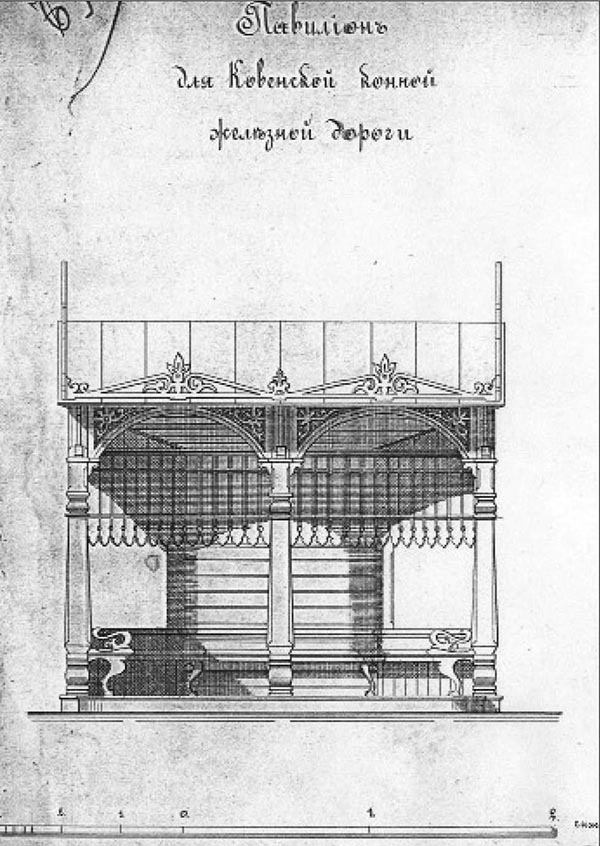

A splendid restaurant with an open terrace (1866) stood in the Municipal Garden (the locale of the current Music Theater). It was frequented by a colorful public that appreciated entertainment and dancing. In 1883, a wooden pavilion for concerts was built in this public garden; it had an elongated hall with a stage and covered side galleries. A park designed for amusements and leisurely walks was established in Žaliakalnis in 1871. Its name was originally Petrovka or Petrovskaja gora, but in 1919 it was renamed Vytauto Park. It had a wooden buffet pavilion, a stage, tennis courts, and swings. A track for a horsedrawn tram (konkė) stretched across the entire city, from the railroad station to Rotušės Square. Wooden passenger stops for the tram were equipped and decorated with carved ornaments in 1897. None of these structures have survived.

|  |

| Project design for passenger stops for the konkė, from Kaunas County Archives, 1897 | |

Wooden public buildings from the interwar period have also not survived. Even the one-story Kurhaus built in the Panemunė Šilas in 1935 by architect S. Kudokas was allowed to deteriorate during the Soviet period. It included a sports gym for skiers, a summer hall, and a buffet. The people of Kaunas greatly enjoyed the evergreen woods in Panemunė, which had footpaths named after local animals and birds, May holidays with live music, and the site of the first camp for scouts. Even President Antanas Smetona took walks or went horseback riding in these woods.

Wooden interwar houses

During the interwar period, the Žaliakalnis and Panemunė districts had the largest number and the most interesting styles of wooden houses. Žaliakalnis was annexed to the city in 1889, but the Czarist army had used the area previously. The development of residential blocks began there only after the First World War. The Žaliakalnis neighborhood has been designated a protected area, due to its unique character. A historic locale near the Gėlių and Minties circles has been entered on the List of Cultural Properties and is maintained in accordance to the 2004 Rules on Protection. Another territory, listed in 2007, stretches from Perkūno Avenue to the Kauko Staircase. The City of Kaunas is currently preparing to declare it a cultural reserve.

The block next to Gėlių and Minties circles in Žaliakalnis, with its network of fanning streets and a planned landscape, appeared as a result of a grandiose 1923 plan for Kaunas. The ambitious city plan was designed by an engineer recruited from Copenhagen, M. Frandsen, and a Kaunas citizen, Antanas Jokimas, as per an order from the municipality. Although the project was unrealistic and utopian, it met with success in the empty plot of pasture land between Vydūno Avenue and Radvilėno Highway in Žaliakalnis, where garden cottages were built. The urban plan is reminiscent of those for a garden city. Here, however, each owner built in accordance 4 Lukšionytė, Miestų medinės architektūros išsaugojimo galimybės.to individual taste and means; there was no effort to achieve the stylistic integrity characteristic of garden cities in England and Germany. Additionally, some homes were built with several rental units. The buildings in this area were eighty percent wooden until 1940; about seventy percent of them survive today. Technically, it is impossible to save them all, although these modest wooden homes are the soul of this locale. Eleven of the more valuable, authentic houses selected for protection represent architecture in wood: the homes at 7 and 20 I. Kraševskio Street, 6 V. Kudirkos Avenue, 45 J. Mateikos Street, 24 and 51 Minties Circle, 23 K. Petrausko Street, and 17, 49, 51 and 55 Vydūno Avenue. When renovating their exteriors, it is essential to recreate their forms in accord with surviving elements. There are other authentic wooden houses under protection, but more flexible regulations apply to them.3

|

| Villa of Antanas Jokimas at 17 Vydūnas Avenue (photo by K. Šilinytė, 2002) |

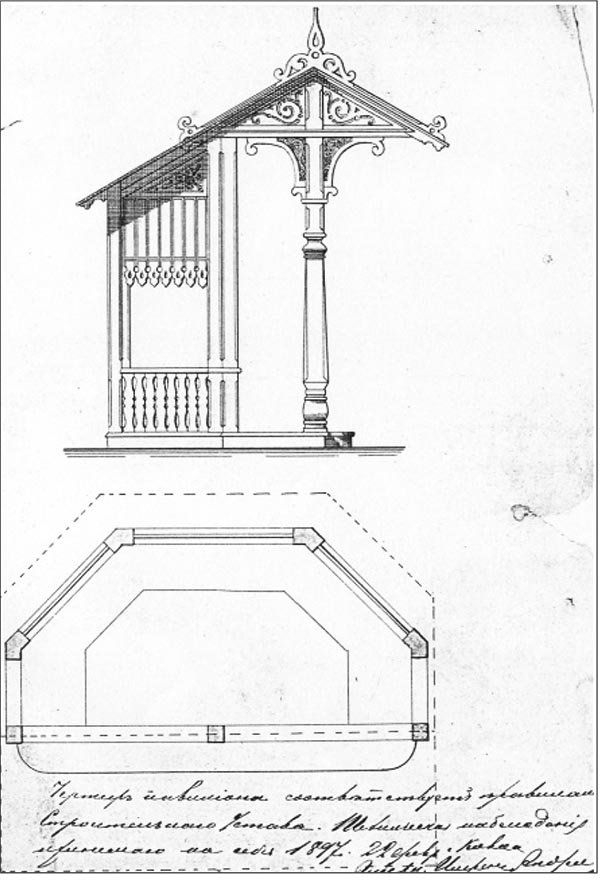

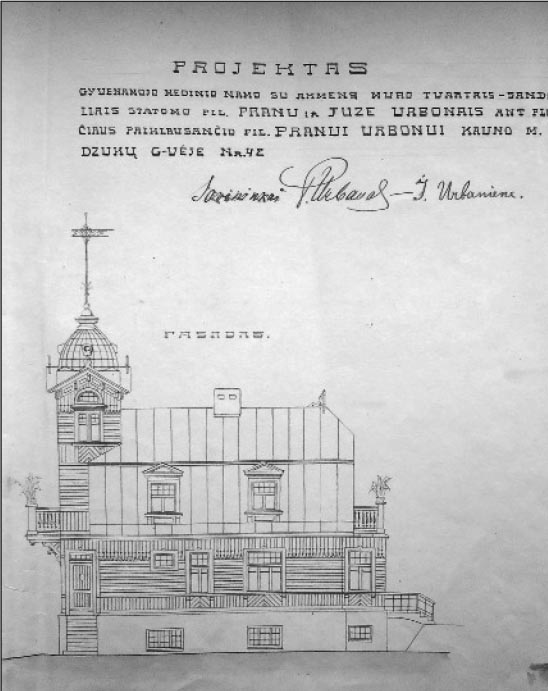

The most popular garden homes in the Žaliakalnis area are one-story structures with tin cottage roofs. These are rectangular, single or duplex apartments. Some are raised with mezzanines and mansards, and others have glassed-in verandas. The open porches include shaped wooden columns. The occasional veranda features geometrically drawn window frames with colored glass panes. The shutters, cornices, chambranles, small pediments, pilasters, and pierced panels give the house its expressive style. The structures of the houses relate to Lithuanian ethnic tradition, but some of the decorative details were designed by professional architects, using simplified neoclassical, neo-Baroque, and Art Deco motifs. Villas were also built in asymmetrical compositions. One of the most impressive was a two-story villa designed by Vaclovas Michnevičius in 1925, which was owned by Pranas Urbonas. It was built on a slope of Žaliakalnis, at 20 Žemaičių Street. A turret with a dome, a curved pediment, and glazed verandas create its expressive style. Carved wooden elements, roof consoles, and frieze bands were used for decoration.

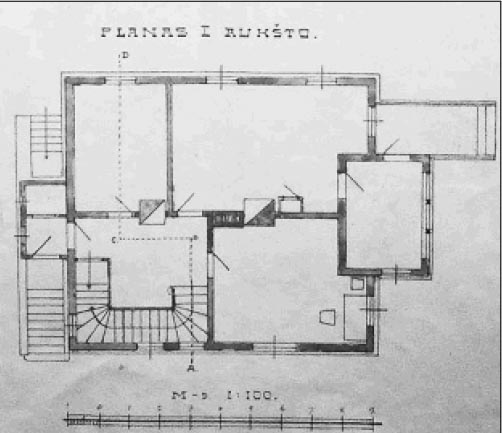

|  |

| Project for the facade for the villa of Pranas Urbonas at 20 Žemaičių Street and first floor plan from the Kaunas County Archives, 1925 | |

Neo-Baroque forms were used to style the villa at 17 Vydūno Avenue, which was designed by the engineer J. Andriūnas in 1924 and owned by Antanas Jokimas. At the time, this villa embodied the quest for a national style. (In the 1920s, Kaunas architects were obsessed with the idea of an original national style.)

Modernistic brick cottages appeared in Kaunas in the 1930s. They were two-story structures in a single mass with tile roofs. Modernism is a less frequent style for wooden buildings; one example is the two-story cottage with a tiled roof at 51 Minties Circle, designed by the architectural technician J. Varneckis in 1935. The windows were large and wide, the siding horizontal, and there was no decoration at all.

The little streets running off Perkūno Avenue and the Kauko Staircase developed spontaneously in harmony with Ąžuolyno Park and the uneven contours of its slopes. The area near the Radio Station (by Perkūno Avenue and Vaižganto Street) is considered especially prestigious. This area, like Vydūno Avenue, was the residence of numerous artists, scientists, political activists, and military officers. Since rental apartments predominated between K. Petrausko Street and Kauko Avenue, the residents were less affluent. One way or another, during the interwar period, Žaliakalnis was ethnically homogenous nearly all its residents were ethnic Lithuanians. Garden Style homes with yards, orchards, and gardens predominate there even today. Impressive villas are rare. There is a distinguished two-story home with a unique porch-terrace at 44 Aukštaičių Street, built in 1927 at the initiative of Captain Antanas Gedmantas. At times, the wooden homes were stuccoed, for example, the house of the Daugvila family at 7 Kauko Avenue. This house was the home of folk artist Elžbieta Daugvilienė, who fashioned distinctive sculptures out of elm bark from 1925 to 1959.

|

| House of Antanas Gedmantas at 44 Aukštaičių Street (photo by N. Lukšionytė, 2007) |

When the area known as Aukštoji (Upper) Panemunė gained official status as a resort in 1933, a plan was drafted for a zone of summer homes and villas on A. Smetonos Avenue, Vaidilos, Pušų, Birutės, Vaidoto, Upelio, and Gailutės streets. This resort area also encompassed the village of Vičiūnai. The wooden summer homes in this resort were designed for the warm season only. There were mineral water and mud bath treatment centers and two beaches in service at the J. Basanavičiaus Šilas. Many of the common, one-story houses with mezzanines have survived in Panemunė. Some are graced with carved window casings and small veranda pediments (30 Upelio Street, 1920), others with ornate mezzanines (5 Vaidilos Street, 1933) and still others with open porches and bay windows (75 A. Smetonos Avenue). The sizable, two-story summer homes are distinctive. The summer home at 28 Gailutės Street (1926) has hexagonal wings with cupolaed roofs. Similar wings frame the facade at 29 A. Smetonos Avenue (1928). Somewhat simpler two-story summer homes stand at 24 Birutės Street (1936) and 19 (1928) and 81 A. Smetonos Avenue (1932). There is a distinctive, asymmetric summer house with a small tower at 8 Vičiūnų Street (1933). Plain modernistic wooden cottages stand at 22 Birutės Street (1937) and 25 Gailutės Street (1937).

|

| Summer home at Gailutės Street 28 (photo by N. Lukšionytė, 2007) |

An original interwar villa with a small tower has survived in Linksmadvaris at 17 Sietyno Street (1935). The form of its mezzanine windows is unusual; the ends of the rafters, roof beams, window casings, and even the battens are profiled; the ridges of the roof are decorated with cresting; and the windows of the small tower have frames with elaborate drawings and carvings. There are instances where the traditions for small manors were followed on Ąžuolų Hill, near the Art School, sculptor Juozas Zikaras selected the usual rectangular footprint for his house at 3 J. Zikaro Street (1933), complete with a studio workshop. It featured folding window shutters and a tiled jerkinhead roof.

The condition of Kaunass wooden heritage and the difficulties of preservation

Neglected wooden buildings were demolished mercilessly during the Soviet years, and their demise continues even now. Todays neglected and deteriorated wooden houses can be said to be living their last days. Others are carelessly renovated: the decorative ornamentation removed; the profiled trim, roofing, and wall materials replaced, and plastic windows and doors added. The appropriate maintenance and restoration of wooden buildings is still not the norm in Lithuania. Owners are not interested, and there is a lack of woodworkers and architects sufficiently knowledgeable in the details of this craft. The restoration of wood features calls for reproduction of their original forms and elements, using the same materials and 52 finishes. New material can only be considered authentic when its type, structure, texture, and color correspond with the character of the original. In this way, although the reproduced parts are new and do not show signs of patina, the reconstruction is recognized as appropriate in terms of maintenance practice for safeguarding architectural heritage.4 For example, following a fire in 2001, the granary of the Kurtuvėnai Manor was accurately reconstructed on the basis of old drawings with the help of this approach.

The originality and value of wooden architecture and the prospects for documentation

Wooden construction is a unique focus for the urban heritage of Kaunas: buildings made of wood reflect the professional architecture involved in the brick structures that followed and the transformed forms of ethnic architecture. Homes of wood were built on spacious lots surrounded by gardens and small orchards. The cultural traditions of the city, the village, and the manor intertwined in such garden homes and villas. Wood and brick construction blended into a natural, organic harmony in Kaunas during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

A database of Kaunas wooden architecture was begun in 2011 with the support of the Kaunas Municipality. It is available for use at this time through the website www.archimede. lt/. The 2012-2013 database development is sponsored by the Research Council of Lithuania. The historic structures are documented by a group of lecturers and Ph.D. and postgraduate students in the Art History Department, Faculty of Arts at Vytautas Magnus University. In this manner, the professional documentation of Kaunass wooden architecture is being collected and shared. It is expected that this website will make information available to homeowners, district administrators, and municipalities, thereby gradually developing public understanding of the aesthetic value of wooden architecture. Expectations are that educational support will grow into a type of public support group, helping people to share their knowledge and experience, and allow the formation of a community interested in the preservation of wooden houses.

WORKS CITED

Jurevičienė, Jūratė. Medinė architektūra istoriniame priemiestyje. Vilniaus Užupio autentiškumas. Urbanistika ir architektūra. 26 (1), 2002, 1117.

Lietuvos architektūros istorija. Nuo XIX a. II dešimtmečio iki 1918 m. Vol. III. Vilnius: Savastis, 2000.

Lukšionytė, Nijolė. Miestų medinės architektūros išsaugojimo galimybės, Urbanistika ir architektūra. 35 (2), 2011, 129-140.

Lukšionytė-Tolvaišienė, Nijolė. Gubernijos laikotarpis Kauno architektūroje. Kaunas: VDU leidykla, 2001.

Lukšionytė-Tolvaišienė, Nijolė. Kauno Žaliakalnio reglamentas ir tvarios raidos nuostatos. Meno istorija ir kritika. 1, 2005, 2431. Online: http://www.vdu.lt/Leidiniai/MIK/index.html

Ross, Juliusz. Architektura drewniana w polskich uzdrowiskach karpackich (1835- 1914), Sztuka 2 polowy XIX wieku. Materiały sesji SHS, Łódź, 1971. Warszawa: PWN, 1973, 151-172.

Surgailis, Andrius. Medinis Kaunas / Wooden Kaunas. (tekstas Nijolės Lukšionytės-Tolvaišienės). Vilnius: Versus aureus, 2008.

Wooden Heritage in Lithuania, Vilnius: R. Paknio leidykla, 2011.