Copyright © 2013 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Editor of this issue: Elizabeth Novickas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2013 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume

59, No.2 - Summer 2013

Editor of this issue: Elizabeth Novickas |

Early Conceptions of Romanticism

in Lithuania

and the Poem

Anykščių Šilelis

GINTARAS LAZDYNAS

GINTARAS LAZDYNAS is an Associate Professor at Šiauliai University and the author of four books. His research focuses on the novel, the theory of the heroic epic, and the aesthetics of Romanticism.

Abstract

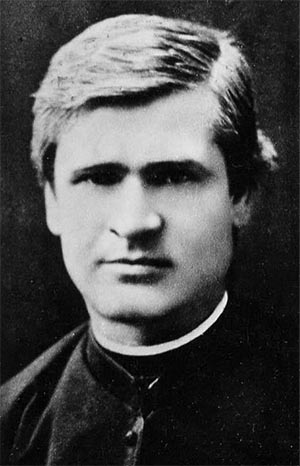

Antanas Baranauskas is known as the author of the poem Anykščių

šilelis. The second most important work in the chronology of Lithuanian

literature, it is traditionally considered the first Romantic poem in

that

literature. This characterization dates from the fourth decade of the

twentieth century, but was not completely accepted until the Soviet

era. This article reconstructs the understanding of the concept of

Romanticism during Baranauskass lifetime and evaluates the poem

from the point of view of the polemics between Romanticism and

classicism. Both Kazimierz Brodziński, an advocate of Romanticism,

and Jan Śniadecki, an advocate of classicism, would have seen Anykščių

šilelis as an example of classical poetry.

Most present-day scholars need no proof that the poem Anykščių šilelis (1858-1859) by Antanas Baranauskas belongs to the Romantic artistic tradition. The poem has been assigned to the Romantic tradition for so long that one seldom entertains the thought that there might have been a time when there was no need to characterize the individuality of the poems artistic thought. Yet there was such a time; it was only in the third decade of the twentieth century that Baranauskas was classified as a Romantic. Until then, the artistic method of Anykščių šilelis had not been relevant to Lithuanian literary criticism. Neither Baranauskas himself, nor the early twentieth-century interpreters of the poem (Dagilis, Šliūpas, Čiurlionienė, Maironis, or Vaižgantas) applied the term Romanticism (or any other term) to the poem. Generally speaking, Romanticism began to acquire the status and substance of a scholarly concept in Lithuanian literary criticism only after the polemics about Romanticism were initiated by Vaižgantas in 1920. However, it did not become fully entrenched until the Soviet occupation of Lithuania. Until the end of the third decade of the twentieth century, Lithuanian critics had little or no conception of Romanticism as a literary method. The discussion between Vincas Mykolaitis- Putinas and Balys Sruoga during their days of study in Munich superficial acquaintance with aesthetic systems, but used their terminology freely and irresponsibly: when Sruoga was asked by Putinas whether he had wearied of everyone categorizing them as symbolists, Sruoga confessed that at the moment he considered himself a Neoromantic1. After his studies at the university in Freiburg in 1922, Putinas enrolled at the University of Munich for another year to attend lectures on literature. The lectures by Professor Fritz Strich about German classicism and Romanticism left a particular impression on him. In that year, Fritz Strich had published a book titled Deutsche Klassik und Romantik oder Vollendung und Unendlichkeit: Ein Vergleich (German Classicism and Romanticism, or Completion and Infinity: A Comparison). It appears, however, that Putinas was not especially enlightened by those lectures:

Without attempting to remember the quite intricate and difficult- to-comprehend philosophical premises of Strichs theories, I remember only that he considered classicism as a perfect completion (Vollendung) and Romanticism as infinity (Unendlichkeit). These are two forms of the manifestation of eternity; they are the two fundamental ideas of the arts. Perfection is changeless serenity; immensity is eternal motion and change. What made a greater impression on me were the characteristics of the classical and the Romantic person and the discussion of the substance and subject matter of their creative work. The former purportedly is the incarnation of reason, a lucid consciousness, and equilibrium, and the latter of restless feelings, longing and angst. The object of the classics works is the world of day, sun, serenity, and joy, while the themes of the Romantic are night, twilight, storm, and pain.

While listening to Strichs, in places very intricate, reasoning and analysis of examples, I was wholeheartedly leaning towards Romanticism.2

Vaižgantas, who in 1927 presented the first comprehensive interpretation of Romanticism in Lithuanian literary scholarship, also relied on Strich.

One can therefore propose that the poems Romanticism is only the result of twentieth-century Lithuanian literary criticisms interpretative relationship with the poem, while Baranauskass relationship to Romanticism remains unclear. Baranauskas did not consciously consider himself part of any literary school; it is conceivable that he did not even know of their existence. If one supposes that Baranauskass self-orientation developed subconsciously and only decades later was determined to be a conceptual coincidence,3 then one would be obliged to speak of an unbelievable marvel, by which the intellectual and spiritual substance of Romanticism reached a remote corner of tsarist Russia and possessed Baranauskass creative soul without his awareness, while the German Romantics needed several centuries of spiritual and theoretical exercises, i.e., deliberate reflections, to attain the same result.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, in her 1910 book Lietuvoje (In Lithuania), Sofija Kymantaitė-Čiurlionienė argued that realism is not at all suited to the Lithuanian soul; the statement elicited a fair amount of discussion, which brought up the concepts of realism, mysticism, symbolism, and modernism, while Romanticism was never even mentioned. Despite her skeptical opinion of the second part of the poem, she had no doubts about Baranauskass poetic talent, although she suspected that it was unlikely that he knew either the rules of composition or the requirements of criticism.4 Nevertheless, she did not emphasize his lack of theoretical knowledge. On the one hand, knowledge of the rules of criticism may not contribute to the value of the creation if the creator has no talent, while on the other hand, knowledge of the rules of poetry does not make a poet rather the poet makes the rules that later scholars of literary criticism study long and hard, searching for food for humanity and rules for future creators. For that reason, it was enough for Baranauskas to have this great talent that guided him along the true way towards the immortality of his name among his fellow-countrymen.5

Emphasizing the demand for new forms at the beginning of the twentieth century, Vincas Mykolas-Putinas wrote that the emergence of new forms is prepared by history and lengthy traditions of artistic creation. At the time, our literature did not have these traditions, and still does not have many.6 In 1938, a translation into Lithuanian of Hyppolyte Taines Philosophie de lart (Philosophy of Art, 1865) appeared in Lithuania. This book helped to lay the foundations for a positivistic approach in literary research, and also presented statements like: to bring a similar art afresh on the worlds stage there must be a lapse of centuries, which will first establish here a similar milieu.7 Much earlier, one of the most renowned thinkers of the era of Goethe and a founder of Berlin University, Wilhelm von Humboldt, asserted that art achieved its current form only because its artists were immersed in the current culture: it [art] had to achieve its current form if it was created by contemporary educated individuals.8

The young Balys Sruoga, Julijonas Lindė-Dobilas, Juozas Keliuotis, and others criticized an epigonic and imitative relationship to Western European literary movements. There were discussions about the search for new forms needed to replace the obsolete classicism. In other words, at the beginning of the twentieth century in Lithuania, it was necessary to perform the same act that, as one stereotypically imagines, was achieved by Romanticism in the beginning of the nineteenth. Considering that Lithuanian literature was not prepared for a renewal of the Romantic form even at the beginning of the twentieth century, how could it have been able to take such a step in the middle of the nineteenth? After all, why did it take until the fourth decade of the twentieth century to establish that Baranauskass poem belongs to Romanticism, notwithstanding that all of the so-called Lithuanian Romantics, from Baranauskas to Maironis, were creating without mastering their own Romanticism? To state that Baranauskas knowingly chose Romanticism would confuse the issue even more. It is clear that he could have referred only to authorities of his own time, such as the Polish poets Adam Mickiewicz and Kazimierz Brodziński, or their opponent, Vilnius University professor Jan Śniadecki, as well as their contemporary, the Russian duke Piotr Viazemski, who had consolidated the Polish and Russian concept of Romanticism that had little in common with that of Vaižgantas or Putinas, or with the Romantic conception that had been evolving after Heinrich Heines treatise Die romantische Schule (The Romantic School, 1835). Furthermore, if Baranauskas had chosen the poem Pan Tadeusz by Adam Mickiewicz as a model to be followed, as has often been argued, then he would have been following the path of realism. In Lithuania, this evaluation of Pan Tadeusz, by the Romantic Mickiewicz, was not surprising. Professor Vladas Dubas of the University of Lithuania described the alterations of aesthetic principles in the poem:

Finally, the poets realism is evident in his descriptions of nature and the plasticity of his landscapes. Generally, the poet does not introduce anything of his own, nor of his feelings toward nature (as the Romantics did). Mickiewicz observes the beauty of Lithuanias nature, the fascination of its fields, its grasslands and its forests [ ]. Nature flourishes on its own in the poets descriptions completely independent of human sentiments or experiences; it lives Homerically.9

It would not be difficult to apply these characteristics to Baranauskass Anykščių šilelis as well. In this case, Putinas would have been correct to call Anykščių šilelis realistic, as he did in an article written during Stalins time.

Romanticism versus Classicism

There has been a persistent tendency in literary studies to explain the substance of a concept by lumping together the synchronic and diachronic conceptions of a term and then linking them genetically with the terms lexical meaning. In other words, all of the content that had ever been linked to a term, historically or lexically, is summed up in the word signifying the concept. This tendency is particularly frequent in the concept of Romanticism, which makes an analysis of the historical development of the term especially difficult.

At the end of the eighteenth century, two fundamental paradigms of Romanticism emerged. The earlier of the two could be called the Romantic paradigm, initiated with the earliest writings of Friedrich Schlegel; while the other paradigm was named Romanticism. The first, the Romantic paradigm, developed from attempts by exponents (especially Schlegel and Novalis), of the Romantic School, as defined by Heinrich Heine, to identify the most important aesthetic features of the new art that gushed from its initial source during the epoch of the courtesans. This concept was intended to characterize the art of the most prominent nations of Europe created between the twelfth and nineteenth centuries. It is not difficult to notice that the early Romantics developed their aesthetic rules by relying upon the historiosophical, anthroposophical, and philosophical attitudes of the eighteenth century. These viewpoints were based on oppositions, such as antiquity/present, sensibility/ reason, subjectivity/objectivity, etc., and were applied a priori to chosen works. Thus, entire cultural epochs were obliged to conform to one single trait, one characteristic, and one artistic rule. All of them were forced into a single corresponding homogeneous system as an integral organic construct, even though many of the various poets were separated by several or even many centuries. This idea predetermined the character of an entire epoch, ignored its intrinsic diversity, and erased artistic individuality.

The second paradigm of Romanticism started crystallizing about 1835, with the analysis of the worldview and world-conception of the representatives of the Romantic School and their aesthetic principles, as described by its creators or expressed in their creations. This concept, as defined by Jacques Barzun, was applied to the art created from 1790 to 1850. However, the definition is often narrowed to the period of the German Romantic school (the Romantic poets of Jena and Heidelberg, Chamisso and Hoffmann, from 1795 to 1830). Franz Thimm, who was one of the first to apply the concept of the Romantic School in his 11 1844 textbook, defines the period of early German Romanticism, probably quite rightly, as the period from 1800 to 1813, bounded by the earlier Sturm und Drang (1770-1800) and by the literature that arose between 1813 and 1820. However, Thimm does not mention E.T.A. Hoffmann at all.10 Paradoxically, even though Friedrich Schlegel, the foremost creator of Romanticisms aesthetic, was the first to use the word romantic to describe the new European literature, the concepts Romantic and Romanticism. These concepts are entirely independent interpretations of artistic principles, despite their similar-sounding names did not become identical. It is quite understandable that, in view of this confusion of terms, both of these systems are combined, mixed, and muddled by grafting and transplanting features of Romanticism onto later art, while at the same time attributing characteristics of new art to Romanticism, without recognizing the heterogeneity of the two systems from the point of view of their religious and philosophical perceptions of the world. This confusion is not restricted to the nineteenth century.

Although the new art form was accepted, the principles of Romantic art bursting upon the scene throughout Europe were meeting active resistance from apologists of the old or classical art. The old controversy about old and new art (Querelle des Anciens et des Modernes) flared up again in Europe. In France, it had been instigated in 1687 by Charles Perrault, who clearly spoke in favor of the new art of the European nations and against emulating ancient authors. A century later, Friedrich Schiller, taking a fresh look at the question, introduced the partition of art into sentimental and naïve, which greatly influenced the young Friedrich Schlegel.

In 1794, Schlegel became actively involved in a discussion concerning the old and the new art. At first, he leaned towards the old art, until Schillers article On Naïve and Sentimental Poets was published in the journal Die Horen,11 which forced him to change his attitude. Refining Schillers differentiation, Schlegel gradually introduced a new dichotomy of the Romantic and the classic (before his acquaintance with Schillers article, Schlegel had tried to develop an opposition of objective and subjective art), which helped to adjust the old classification of art. Schlegels conclusion drew on research done on the greater part of Greek, Roman, and some of the literature of the Middle Ages. None of the English (Wordsworth, Coleridge), French (de Staël, Chateaubriand) or German (Novalis, Wackenroder) works had been written yet, therefore, they could not have been material for Schlegels study and classification.

During a conversation between Johann Eckermann and Johann Wolfgang Goethe, the latter claimed that it was he and Friedrich Schiller who came up with the binary opposition of Romantic and classical, and later the Schlegel brothers seized upon it and developed:

The concept of classical and Romantic poetry that has now spread over the whole world and occasions so many quarrels and divisions, Goethe continued, came originally from Schiller and myself. I laid down the maxim of objective treatment in poetry and would allow no other; but Schiller, who worked very much in the subjective way, deemed his own approach to be the right one and composed his essay upon Naïve and Sentimental Poetry in order to defend himself against me. He proved to me that, against my will, I was Romantic and that my Iphigenia, through the predominance of sentiment in it, was by no means as classical or as conceived in the spirit of antiquity as many people supposed. The Schlegels took up this idea and carried it further, so that it has now been disseminated throughout the world, and now everyone talks about classicism and Romanticism, something no one gave any thought to fifty years ago.12

Essentially, Goethe was not entirely right. It was not the opposition of old and new art that Friedrich Schlegel rethought in his early writings and labeled as classical and Romantic art, which was certainly given impetus by Schillers article. The turning point of all of these ideas was conveyed through the secondary consciousness of the influential and aristocratic French writer Anne Louise Germaine baroness de Staël, widely known as Madame de Staël. In 1813, de Staël, the author of such novels as Korina and Delphina, published a book About Germany, which unexpectedly introduced all of Europe to the German allocation of literature into Romantic and classical. Madame de Staël also introduced the identification of Romantic literature with German literature and classical with French literature. This link implied a new opposition, later emphasized by Heinrich Heine, between Protestantism and Catholicism. Soon enough, all of Europe, as well as Poland and later Russia, started to divide literature into Romantic and classical, as if this division had existed since time immemorial.

Contemporary creators who consciously considered themselves representatives of the new art (Coleridge, Wordsworth, Stendhal) or those who demanded arts renewal (Tieck, Chateaubriand), were all labeled Romantics. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, writers who divided themselves into camps of Romantics and classicists, using Schlegels principles, eventually had to reclassify themselves under the worldview principle of Romanticism. In consequence, many of them lost their status as Romantics. Stendhal, who called himself a furious Romantic, as well as Baudelaire, fascinated by Schopenhauers philosophy, suffered the same fate; however, their elder contemporaries, who did not know about the opposition of Romanticism-classicism at the time they created their most important works, for example, de Staël, or Chateaubriand, who violently defended the basic aesthetic principals of classicism, remained Romantics.

The Spirit of German Poetry

Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) followed Schlegels position on Romanticism. Later, according to his own words, he organized an extermination campaign against Romanticism. Nevertheless, he was the first to define Romanticism as an artistic movement. In his polemic, the article Die Romantik, (1820), he developed his fundamental theoretical statements that were later repeated in his essay The Romantic School: the cyclical vicissitudes of Romanticism and classicism, the sensual intoxication of antiquity (the reason people enjoyed an outer observation and representation of the objective world) and the spirituality introduced by Christianity that awakened a secret thrill of the heart, perpetual longing, and bliss. Conveyed through the poetic word, these initiated Romantic poetry, which blossomed during the Middle Ages but was soon suppressed by constant military and religious conflicts. In Heines era, it was reborn in Germany and produced its prettiest flowers, such as Goethe and Schlegel. Heine refused to accept the division of Romantic (obscure, colorful) and plastic poetry because the images through which those Romantic feelings should be excited can be just as clear and be drawn with just as clear outlines as the images of plastic poetry.13 That is why he considered Goethe the most plastic poet, but still a Romantic. Christianity, and the institution of knighthood, had a tremendous impact on the development of Romantic poetry. However, both of them were only the means of introducing Romanticism, which had already long since established itself as the spirit of German poetry. A few years later, Heine emphasized that the Romantic School in Germany was something quite different from that designated by the same name in France and its tendencies were totally diverse from those of the French Romanticists.In other words, Heine had already noticed that two phenomena of different origin were designated by the same name in Germany and France. But what was the Romantic School in Germany? asks Heine, and answers his question, stating:

It was nothing else than the reawakening of the poetry of the Middle Ages as it manifested itself in the poems, paintings, and sculptures, in the art and life of those times. This poetry, however, had been developed out of Christianity...14

Kazimierz Brodziński

The polemic between Romantics and classicists flared up in Poland in 1818; in Russia, it took place in 1824. An echo of this battle had reached Vilnius as well. One initiator of the polemic was the notable Polish sentimentalist poet and literary critic Kazimierz Brodziński,15 who became famous on account of his broad study O Klassyczności i Romantyczności, tudzież uwagi nad duchem poezyi polskiej (On Classicism and Romanticism, As Well as on the Spirit of Polish Poetry, 1818). Between 1842 and 1844, after the writers death, ten volumes of Brodzińskis collected work were published in Vilnius. The study mentioned earlier is included at the very beginning of the fifth volume.

Barely 27 years old and a professor at Warsaw University, Brodziński had mastered idealistic German philosophy very well. He approached Johann Gottfried Herders idea of national character, as was typical for the Enlightenment, as a totality of that nations particular features, which appear in every literature. He was convinced that the most appropriate genre to convey Polish spirituality was the idyll. Soon afterwards, he himself wrote the idyll Wiesław (1820); however, it pleased neither the new, nor the old art adepts. The reason behind this might be that, as a moderate, Brodziński was searching for the strongest features of Romantic and classical trends, and tried to harmonize them.16 Brodziński, instead of constructing one, classical, collection of rules, constructed yet another, a Romantic one, based on the same superficial principle of the regulation of artistic images. In this sense, he kept to the principles of classicist aesthetic thinking.

Unlike Romantics such as Novalis, Schlegel, and Schelling, Brodziński returned to the eighteenth centurys primary binary opposition of nature and culture, along with its consequent oppositions of reason and sensibility, body and spirit. Reason and body are the features of classicism, while sensibility and spirit belong to Romanticism. New binary oppositions crystallize that will be used by many upcoming critics to define Romanticism:

Classicality limits imagination, leading it to a single object; while Romanticism lifts one up from material things to infinity; in the former, imagination is external and physical, in the latter, it is internal and perpetual. The material body was everything to Homer, and spirit is everything to our Romanticists. The first one is bright day, in which this infinity seems limited to us; the second one is night, which reveals the same infinity and offers the entire emotive content of things, and not the things visible to the eye.17

Brodziński does not argue with Madame de Staëls statement that Romanticism starts with the epoch of the courtesan and is infused with the spirit of knighthood and Christianity,18 or that it primarily depends on the nature of the relationship between knighthood and Christianity, and on Roman and Greek literature. Looking at the opposition of Romanticism and classicism from a nationalistic Polish point of view, Brodziński introduces the component de Staël emphasized, that is, the regular patterns of German and French artistic thought correspond to the contradiction between Romanticism and classicism. Brodziński tasked himself with finding Polish literatures place among French and German literary canons. The cultural authority of the great nations powerfully constrained possible aspirations to originality and the freedom to interpret both Polish and Russian literature. There was only one possibility left for the Polish and Russian nations to intervene in the dialog uninvited, without hope of being heard beyond the homelands walls; to listen to what French or German authorities discussed, and to plunge into variations of topics suggested by Boileau, Winckelmann, Schlegel, or Madame de Staël. It did not matter how strongly feelings of national pride resisted it, but at the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century, the great Western cultures served as a model to Russians and Poles, just as the ancient world was the model for the French in the seventeenth century. Nothing remained for Brodziński but to reluctantly acknowledge that in Poland, some follow the French, while others try to follow the Germans, but in both cases there was imitation and replication, not original art.19

Classical is Healthy, Romantic is Diseased

In all of the nations, adepts of the classics fought against the principles of the new art in the same way. Art, for the naïve poet Goethe, had not yet become a subjective expression of the contents of the human spirit; art is objective, existing beyond the boundaries of the human soul. For this reason, he maintained the value of representation: there is the true (classical) and untrue (Romantic) art, or distortion of true art, which Goethe consistently, and without the least tolerance, fought against until the end of his life. In his famous maxim, he compared both of these tendencies to the opposition of health and illness: Classisch ist das Gesunde, romantisch das Kranke (Classicism is health, and Romanticism is illness).20 In 1829, in an interview with Eckermann, Goethe could not hide his disgust with the Romantics:

Trespassing the Perfect Rules

Jan Śniadecki, a professor at Vilnius University, responded to Brodzińskis article in a Goethe-like spirit. He felt a threat coming from the Romantics to the long-lived, well-established rules. In his 1819 article O piśmach klasycznych i romantycznych (On Classical and Romantic Writings), he defends the finished forms the world had acquired and was no longer willing to change. Like Brodziński, he applies a systematic approach to literature, that is, he upholds a view criticized by Mickiewicz, who stated that some writers see only classicism and Romanticism in all poetry, and they sort all writers works, from Orpheus to Byron, to the left or to the right, labeling them as either classical or Romantic.22 Actually, Mickiewicz does not use the terms classicism and Romanticism, which signify subjection to a concrete literary method; he uses instead concepts such as classicality and Romanticity, which indicate the particular stylistic features of those groups of works.

Śniadecki maintains the position common to the old apologists, which derives from a creationist worldview the world was created a long time ago, and so the rules and regulations of perfection were established long ago, and therefore, one may either follow them or not. Classic art conforms to poetic rules set for the French by Boileau, for Poles by Dmóchowski, and for the rest of the civilized world by Aristotle and Horace. Romantic art breaks these rules of perfection and destroys them. In other words, if Boileau or Horace established the rules of perfect art, logically, the art that denies them is simply imperfect. The arguments presented by Śniadecki best illustrate that the collision between Romanticism and classicism was primarily a collision of creationism and evolutionism: if all the laws of human existence are inscribed into human nature, and ancient Greek art and philosophy defined them most accurately, then receding from the Greeks is receding from truth and perfection. This is purportedly what Romantic or new art occupies itself with.

Without mentioning a single Romantic work, Śniadecki condemns Romanticism for offering figurative meanings instead of explaining things simply and literally. Shortly afterwards, in 1822, Piotr Vyazemsky ironically ridiculed adepts of classical regulations who did not understand figurative meanings, and demanded that Pushkin, in his poem Kavkazskii plennik (The Prisoner of the Caucasus) of 1822, clearly explain that the Circassian girl jumped into the water and drowned herself because it was too difficult to understand what the verse meant: As moonlight waters splash ahead / A rippling circle disappears.23 Similarly, Śniadecki highlighted only a realistic meaning, a oneness with nature, and refused to accept the magic, spells, and ghosts the Romanticists purportedly portray.

The purposes of art include entertaining the reader, along with educating him or her and providing knowledge. However, Śniadecki obsessively shook off the memory of humanitys childhood; he could not analyze it, he could not see its image because this image degraded and disgraced him. Śniadecki was a civilized person who had risen from a primeval state; he did not want to remember his past, because a juxtaposition with the past, basically, suggests his evolution. The creationists consciousness interprets this evolution as an emphasis on human limits: man understands his present state as the peak of perfection, and any reminder of the path that led him to this state, in other words, his previous imperfection, humiliates and frustrates him. Only a human who has reached a present state of perfection and who is guided by reason and sees things as they leave an imprint on the senses (the eyes and lenses) can represent them. In this case, the most convenient approach is to identify oneself with the ancient authorities and humbly and submissively acknowledge their perfection: For two thousand years, we respected appointed laws that were confirmed by truth and experience; let us obey them (...)24

Unlike Goethe, Polish Romantics did not actualize the problem of the concepts origin; they approach them as if they were new, but intrinsically understandable, as if they had existed for centuries. On the other hand, one cannot find any references to the research done by Friedrich Schlegel, which is replaced by a short compilation from Madame de Staëls book On Germany. The principles of Romantic and classic art formulated in a chapter of de Staëls book become a starting point for subsequent development and realization. As we have seen, until the middle of the nineteenth century, Romanticism and classicism, or the old and the new art, are understood as the expression of two types of worldview the spiritual versus the physical, the emotive versus the rational, and from there, as the variation of two topics, two styles, braced against Greek-Roman and Christian religion, the ancient and the Middle Ages, and ultimately, as the embodiment of the German and French nations spirits.

Perception and Belief

Four years after Brodzińskis study was published, a young Adam Mickiewicz entered the quarrel. Zavadskiss publishing house in Vilnius published a collection of poems, Poezje (Poetry), by Mickiewicz in two volumes in 1822-1823. The book traditionally marks the beginning of Romanticism in Polish literature, and the collections foreword, O poezji romantycznej (On Romantic Poetry) became a manifesto of Polish Romanticism. If the revolution enacted by Mickiewicz, wrote Czesław Miłosz, did not lead towards a quick victory of the Romantic spirit over rationalism, it at least introduced a new understanding of poetic language.25 In this foreword, as well as in the ballad Romantyczność (Romanticism) created in January 1821, Mickiewicz actively involved himself in the still-smoldering polemic on Romantic and classic poetry.

In Romantyczność, Mickiewicz portrayed an old rationalist, who, with the passion of Jan Śniadeckis anti-Romantic article, attacks the emotive mystical worldview, and to the ordinary people witnessing a miracle, he says: Trust my sight and my lenses, / I see nothing here. A poet calmly explains the rules of the new art to him:

The

girl feels I modestly answer,

And the crowd believes profoundly;

Feeling and faith speak more clearly to me

Than the lenses and eye of the sage.26

Classicalitys advocate follows dead truths, unfathomable to people, and since he does not know the living truth, he will never see a miracle.27 One can see a miracle only with ones heart, not with the eyes. In the Lithuanian translation of Romantyczność by Eduardas Mieželaitis, the opposition of live/dead truth disappears (Tu juk negyvą tiesą tegynei. / Ji ir neleidžia patirti / Tau šio stebuklo, pažįstamo miniai. / Žvelk širdimi tik į širdį), and so does the unity of feeling and belief (Ji, atsakiau aš seniui, tai jaučia. / Žmonės ja tiki. Man regis / Jausmas pasako žymiai daugiau čia, / Nei akiniai arba akys28): Dziewczyna czuje, odpowiadam skromnie, / A gawiedź wierzy głęboko; / Czucie i wiara silniej mówi do mnie / Niż mędrca skiełko i oko.29 It is precisely feeling and metaphysical belief, with a distinctive religious shade, which reveal the deep existence of things and allow seeing a miracle the soul of her deceased beloved that appears to Karusia a miracle impossible to see with either the eyes or lenses. In the translation, metaphysical belief is reduced to trusting what Karusia says.

Apologists for the old art were not the only ones Mickiewicz disagreed with. In some respects, he disagreed with Brodziński, a promoter of the new art, to whom Mickiewicz dedicated a remark in the foreword of Poezje and a Romantic speech in Forefathers Eve, Part IV. This was a disagreement inside the camp. Brodzińskis goal, to define static systems of classicism and Romanticism and to set all previous and present poetry into these systems, is unacceptable to Mickiewicz. Like Madame de Staël, Mickiewicz introduces a diachronistic principle; he considered the relationship of imagination, sensibility, and reason, as well as a nations language, as the essence of poetry. The other important distinctive constituent of poetry is its audience. There is poetry created for ordinary people, and there is poetry created for the chosen. Mickiewicz completely depreciates the ancient Romans because a strange culture, borrowed from the Greeks, interrupted the natural development of its national culture.30 In Greece, art found more fertile ground and blossomed as a balance of imagination, sensibility, and reason, and gave works of art harmony of structure and expression. Besides, the poet said,

during the heyday of their culture, Greek poets always sang for the people; their songs contained the nations feelings, attitudes, and memories, adorned with ingenuity and a pleasing structure, and consequently they had a major influence on maintaining, strengthening, and even forming the nations character. 31

Precisely this kind of art is called Greek or classical art (klasyczny).

Chivalry, love of the fairer sex, observance of the code of honor, religious ecstasy, and a blend of pagan and Christian mythical images compose the medieval Romantic world, whose poetry is also labeled as Romantic. 32 Both arts are composed of spirit and form, or content and external form. As the new European nations matured, the beauty of antiquitys art discloses itself to them, and literate poets could no longer be indifferent to it. Poets imitating the poets of antiquity create various possibilities of a synthesis of form and content, but poetry cannot be the same as it was in ancient times. Initially, nationalistic topics dominated, because the ancients oeuvre was not popular. Later, more order, harmony, and refinement33 were introduced into the Romantic world. Romantic poetry was shaped by a nations particular tendencies, and real Romantic works should be sought for in the oeuvre created by medieval poets,34 while the rest of the later Romantic oeuvre, considering the content and structure, form and style, leans towards other kinds of poetry. To Mickiewicz, Romantic literature is, in a sense, identical to the courtesan literature of the Latin nations.

When Mickiewicz wrote about the genre of the ballad, he made no mention of Coleridges Lyrical Ballads, which appeared in 1798. Its Introduction, written by Wordsworth for the 1800 edition, is considered the manifesto of English Romanticism. Mickiewicz does not mention any of the representatives of German Romanticism either, except for Schlegel (Friedrich, judging from the context), whom he actually reproached for providing an inaccurate definition of Romantic literature.35 Brodziński as well as Śniadecki, the opponent of Romantics, write of Romanticism in a similar manner, using broad strokes and without referring to specific works.

Anykščių šilelis Classical or

Romantic?

Anykščių šilelis Classical or

Romantic?

To which of those two arts would a literary proficient attribute Antanas Baranauskass poem Anykščių šilelis when it was written in 1858? Accepting Brodzińskis definitions, that classicality restrains imagination and leads it to a single thing, while Romanticism liberates the imagination and, instead of portraying things as seen with the eyes, offers their content as it is felt (in a sense, the very essence of Kants thing-in-itself), the literary proficient would undoubtedly describe Baranauskass artistic method as classical, as an art of daylight and emphatic materiality. Clearly, Baranauskas does not concern himself with presenting the emotive content of things. Instead, he presents things seen with the eyes, arranged in the emotively limited external world. Baranauskass hero enters a forest armed with four senses:

Kur

tik žiūri..., Kur tik uostai..., Kur tik klausai..., Ką tik

jauti. 36

(Wherever you look

, Wherever you smell

, Wherever you

listen

, Whatever you feel

)

He does not try to struggle through

the surface of the

thing-in-itself. Instead, he is satisfied with conveying the static

physical content, reminiscent of a scientist-naturalists compilation

of a list plants in the making:

| Čia paliepių torielkos po mišką išklotos, | There under the lindens, ox-eyed daisies, blanketed through the woods |

| Čia kiauliabudės pūpso lyg pievos kemsuotos, | There the milkcaps poke out, as if the fields were covered in hillocks, |

| Čia pušyne iš gruodo išauga žaliuokės, | There in the pines, the green elfcups grow from the frozen earth, |

| Čia rausvos, melsvos, pilkos ūmėdės sutūpę, | There ruddy, bluish, gray toadstools squat, |

| Linksmutės, gražiai auga, niekas jom nerūpi, ...37 | Cheerful, growing nicely, without a care, ... |

In the forest, the poet does not see anything beyond his

eyes and lenses; a picture of external nature is a miracle to

him, and nature itself, for Baranauskas, is not the thing-in-itself

that conceals the great secret. Instead, using Julijonas Lindė-

Dobilass words, it is Gods most beautiful creation. Nature as

depicted by the poet is prettified and decorated, as if an experienced

gardener had cleaned up its primitive wilderness

that, purportedly, is so beloved by the Romantics, yet disgusts

Śniadecki. Reason and perception dominate in the poems imagery.

However, imprints of imagination are marginal everywhere,

there is no mystical infinite power of seeing, 38

which

Śniadecki considers a Romantic fallacy, and Mickiewicz so

particularly valued. But Baranauskas also never uses the figurative

meanings of words, which so frightens classicists. Even

in the second part of the poem, historical memory and rational

decisions dominate over imagination. Undoubtedly, the

strictly well-formed plan of the poem, especially the first part

of it, could be assigned to the features of classicism. Relying on

Mickiewiczs rules, the very feature that draws Anykščių šilelis

even closer to Greek or classic art becomes a very important

argument for Lithuanian literary studies to attribute Anykščių

šilelis to Romanticism: Baranauskas sings for the people,

not

for the chosen. His song consists of the nations feelings, attitudes,

and memories, adorned with ingenuity and a pleasing structure. Several

folklore elements in the poem could also be

assigned to this category (for example, the story of the Puntukas

Stone and the fairytale about Eglė, Queen of Serpents).

Referring to the early conception of Romantic and classic art, one must acknowledge that the largest part of the artistic features in Anykščių šilelis fulfills the conception of classical art and leaves very few arguments to prove the poems Romanticism. Wendell Mayo also questions the Romantic label of Anykščių šilelis by saying: Still, critics continue to identify a strong bias in the poem rooted in a Romantic tradition. If the poem continues to be identified as Romantic it is only because historical forces have [t]ended to center meaning that way.39 Therefore, despite the fact that the poem was associated with the aesthetics of Romanticism in the middle of the nineteenth century (referring to the aesthetics of Romanticism, as conceived by Vaižgantas, Putinas, or subsequently, Vytautas Kubilius), it is possible to state that for Baranauskass contemporaries, Anykščių šilelis fits perfectly into the rules of classical art. And if we assume Baranauskas deliberately chose an artistic method, the more conservative pole of this opposition classicism would have attracted him as more suitable to the poets cultural nature: Baranauskas was, according to Vytautas Kavolis, a person of a static, not a dynamic, world; Baranauskas was afraid of change and therefore avoided it. Later evaluation of the poem was not determined by new discoveries, or deeper insights into the poems artistic essence. Instead, it was determined by the high regard given the paradigm of Romanticism, which substituted for the concept of Romantic and classical in Lithuania, as corresponding better to the nations spirit, despite the drastic changes in this paradigm in the last hundred years.

WORKS CITED

Baranauskas, Antanas. Anykščių

šilelis. Vilnius: Baltos lankos, 1994.

Brodziński,

Kazimierz. Dziela

Kazimierza Brodzińskiego. Vol. 5. Wilno: T. Glücksberg,

1842.

ČiurlionienėKymantaitė,

Sofija. Raštai.

Penki tomai. Vol. 4. Vilnius: Vaga, 1998.

Dubas,

Vladas. Literatūros

įvadas. Kaunas, Marijampolė: Dirva, 1928.

Eckermann,

Johann Peter. Gespräche

mit Goethe in den letzten Jahren seines Lebens. II Teil.

Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1837.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Sämmtliche Werke in dreissig Bänden. Band

3. Stuttgart: J. G. Cottascher Verlag, 1857.

Heine,

Heinrich. Sämmtliche

Werke. Band 13. Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe, 1862.

_____. Heines Werke.

Band 4. Berlin, Weimar: Aufbau-Verlag, 1976.

Humboldt,

Wilhelm von. Gesammelte

Werke. Band 4, Berlin: G. Reimer,1843.

Jurgutienė,

Aušra. Naujasis

romantizmas iš pasiilgimo. Vilnius: Lietuvių literatūros

ir tautosakos institutas, 1998.

Lietuvių literatūros istorija.

Vilnius: Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos institutas, 2001.

Mayo,

Wendell. A Note on

Oppositional Discourses in Baranauskass Anykščių Šilelis.

Lituanus,

Vol. 45, No. 1, 1999.

Maironis

(Mačiulis, Jonas). Raštai.

Vol. 3, Book 2. Vilnius: Vaga, 1992.

Mickevičius,

Adomas. Lyrika,

baladės, poemos. Vilnius: Vaga, 1975.

Mickiewicz,

Adam. Pisma,

Vol. 3 Paryż. 1844.

_____.

A New Translation of Adam Mickiewiczs Romanticism. Translated by

Angela Britlinger, Sarmatian Review, Vol. 12, No. 3. Accessed March 16,

2013 at:

http://www.ruf.rice.edu/~sarmatia/992/britlinger.html

Miłosz,

Czesław. The History of

Polish literature. University of California Press, 1983.

Mykolaitis-Putinas,

Vincas. Raštai.

Vol. 7. Vilnius: Valstybinė grožinės literatūros leidykla, 1968.

Mykolaitis-Putinas,

Vincas. Naujosios lietuvių literatūros angoje. Židinys, 1928. Nr.

10. P. 212-220.

Śniadeckis,

Janas. Raštai.

Filosofijos darbai. Vertė R. Plečkaitis. Vilnius: Margi

raštai, 2007.

Staël-Holstein,

Anne Louise Germaine de. De

LAllemagne. Paris, Londres: John Murray, 1813.

Taine,

Hippolyte. Lectures on

Art, second series. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1880.

Thimm, F. The Literature of Germany. London, Berlin: D. Nutt, 1844.

Vyazemsky,

Piotr Andreievich. Estetika

i literaturnaja kritika. Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1984.

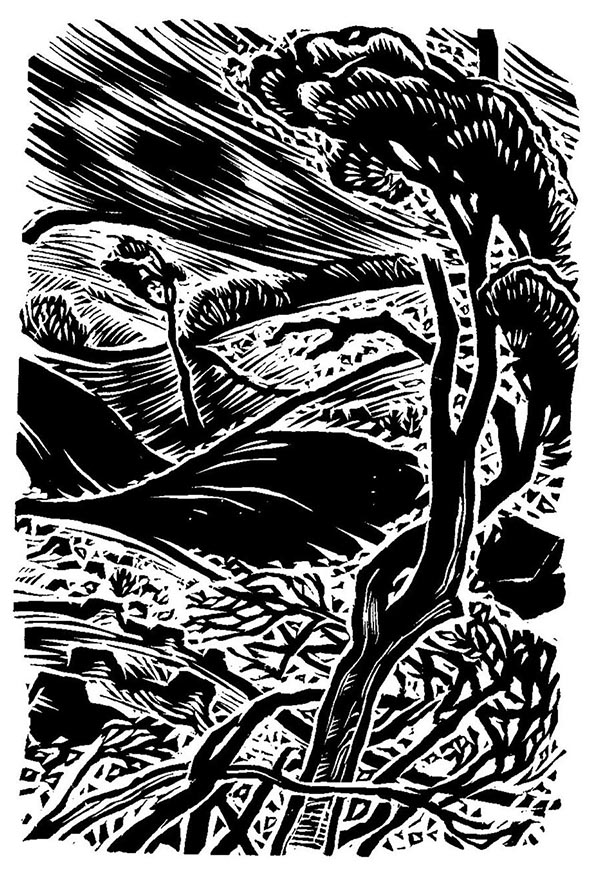

Illustration by Vytautas

Valius from Anykščių šilelis, 100 metų,

Vilnius: Valstybinė

grožinės literatūros leidykla, 1959.

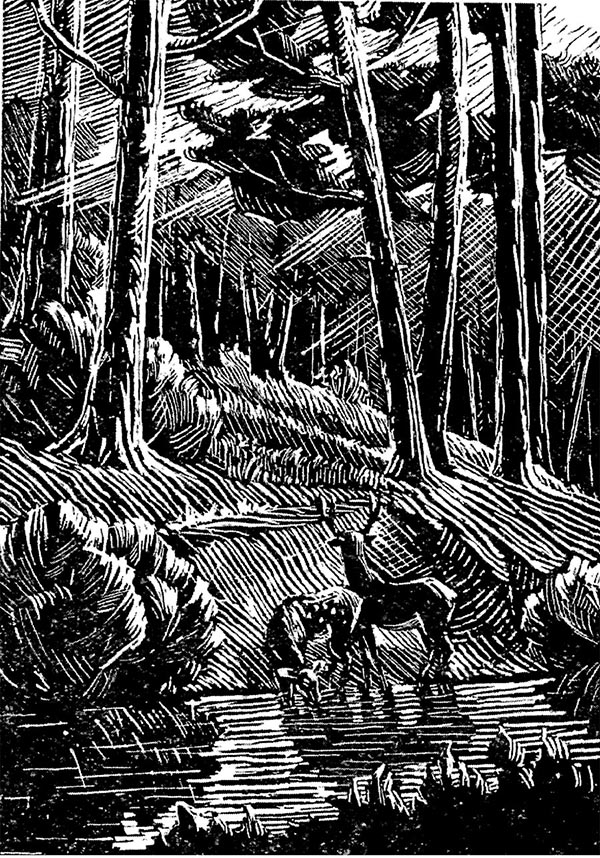

Illustration by B. Klova

from Anykščių šilelis,

Kaunas:

Valstybinė pedagoginės

litertūros leidykla, 1959.

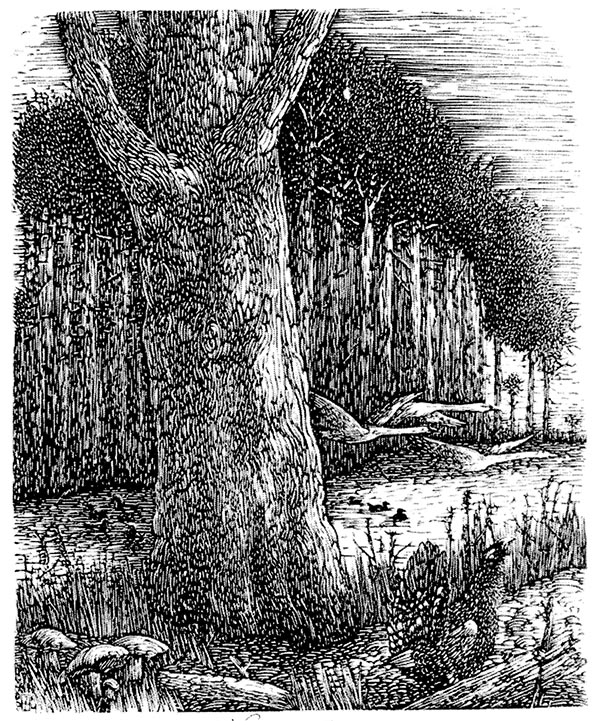

Illustration by Alfonsas

Žvilius from Anykščių šilelis,

Vilnius: Vaga, 1985.