Copyright © 2013 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Editor of this issue: Elizabeth Novickas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2013 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume

59, No.3 - Fall 2013

Editor of this issue: Elizabeth Novickas |

“Ten Days That Shook Lithuania”:

The Atgaiva Drama Festival of 1988

PATRICK CHURA

PATRICK CHURA is Professor of English at the University of Akron, where he teaches courses in American literature. His recent book, Thoreau the Land Surveyor, won the College English Association of Ohio’s Dasher Award for outstanding literary scholarship.

All translations from Lithuanian language texts are by Patrick Chura.

Abstract

The article tells the story of the Atgaiva Drama Festival, thefirst

Lithuanian drama festival to take place outside the austere

ideological restrictions of Soviet censorship. It then analyzes

the complicated social and political impact of the event, which

was immediately recognized as a catalyst to cultural renewal

in the Glasnost era.

A stated goal of the Atgaiva festival, held in Điauliai in

December 1988, was “to stimulate the participation of theater

professionals in the revival of Lithuanian national culture.”

Each of the plays presented at the festival expressed some form

of anti-Soviet protest and carried liminal messages about the

captive position of colonized cultures under Soviet hegemony.

Studied in its entirety as a unified narrative, the Atgaiva festival

may be read as a declaration of Lithuanian cultural independence

from the Soviet Union that preceded the country’s

political declaration of independence by some fifteen months.

Viewed with hindsight, the festival also contained important

forewarnings of the painful disillusionments that immediately

followed the restoration of Lithuanian autonomy.

To mark the fifty-fifth birthday of director Gytis Padegimas

in February 2007, Antanas Venckus, head of the Điauliai City

Theater, wrote a letter to the city’s mayor. The letter’s purpose

was to announce a celebration being planned by theater personnel

and to request that the Điauliai municipal government issue

an official commemorative proclamation about Padegimas’s career.

The first accomplishment Venckus cited in his missive was

a politically charged theater festival Padegimas had conceived

and organized in Điauliai in 1988, “the Lithuanian Drama Festival

– Atgaiva.” This event, Venckus noted, was “colored with

ideas of national rebirth” and “had powerful repercussions in

the theatrical community.”1

Venckus’s praise for his longtime colleague and the Atgaiva festival was well-deserved, sincere, and long overdue. In 1988, Atgaiva had been celebrated as a turning point in Lithuanian theater history and a catalyst to cultural renewal in the Glasnost era. During the tumultuous period between the festival and Venckus’s letter, however, the event and its significance had been largely forgotten, a victim of the severe disillusionments that followed swiftly upon the realization of independence in 1990. Though Atgaiva had bolstered the country’s selfassurance at a key moment, that confidence had waned during the crises of national identity that preoccupied Lithuania in the 1990s and beyond.

The fall of 2013 therefore seems a fitting moment for another remembrance, even longer overdue. Marking the approach of the twenty-fifth anniversary of Atgaiva – the first Lithuanian drama festival to take place outside the austere ideological restrictions of Soviet censorship – offers the chance to take stock of the event as a cultural moment that foreshadowed, and to some extent contributed to, both the restoration of Lithuanian autonomy and the imminent break-up of the USSR. Considering the fact that several of the festival’s plays displayed or debated the influence of the United States on Lithuanian society, the project also illuminates meaningful relationships between American culture, Lithuanian culture, and anti-Soviet dissent.

Loosely translated, the word atgaiva means “renewal” or “revitalization.”2 The stated goals of the Atgaiva festival were “to produce the best Lithuanian classic and contemporary dramatic works, and to stimulate the participation of theater professionals in the rebirth of Lithuanian national culture.”3 The euphoric response to Atgaiva in its immediate context clearly indicated that it had lived up to the hopes articulated by Padegimas, its primary organizer and driving force. Promoting the festival in 1988, Padegimas envisioned it as “a means of analyzing the nation’s consciousness,” rediscovering the “essential values” of its people, and “returning status” to a national theater that had been “forced to adjust itself to the priorities of the Ministry of Culture” for far too long.4

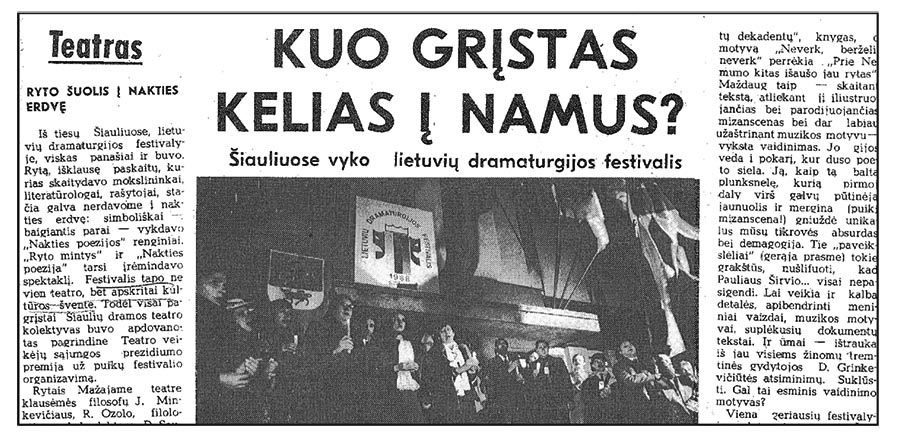

Remembering Atgaiva in a recent interview, Padegimas spoke nostalgically about the “great citizen activism” that surrounded the festival. “Every night there were crowds of people out in front of the theaters with flags, with candles, and with songs,” he recalled, “Immediately, the events became political rallies of a new kind.” “Atgaiva,” Padegimas asserted, “gave people inspiration, reassuring them that they could dare, that they did not need to be afraid.”5 Such recollections help explain why one Atgaiva participant, actor Povilas Stankus, began his acceptance speech at the post-event awards ceremony with the words, “Gytis Padegmas, I kneel down before you for giving us such a festival.”6

|

| Atgaiva festival opening ceremonies. Organizer Gytis Padegimas recalled, “Every night there were crowds of people out in front of the theaters with flags, with candles and with songs.”Tiesa, January 4, 1989. |

But the great festival almost didn’t happen. In the fall of 1988, less than three months before it was scheduled to begin, the presidium of the Union of Lithuanian Theater Professionals, under pressure from the Soviet Ministry of Culture, resolved to postpone the event until March of the following year. The ministry had become aware of the festival organizers’ intent to take advantage of a moment of Glasnost-era “openness” by using the theater to celebrate Lithuanian culture and to interrogate the dubious effects of nearly five decades of Soviet occupation. Understandably nervous about the event, the ministry requested the postponement so the event could be truncated and politically neutralized by merging it with the following year’s traditional Soviet “Theater Day” celebration.

|

|

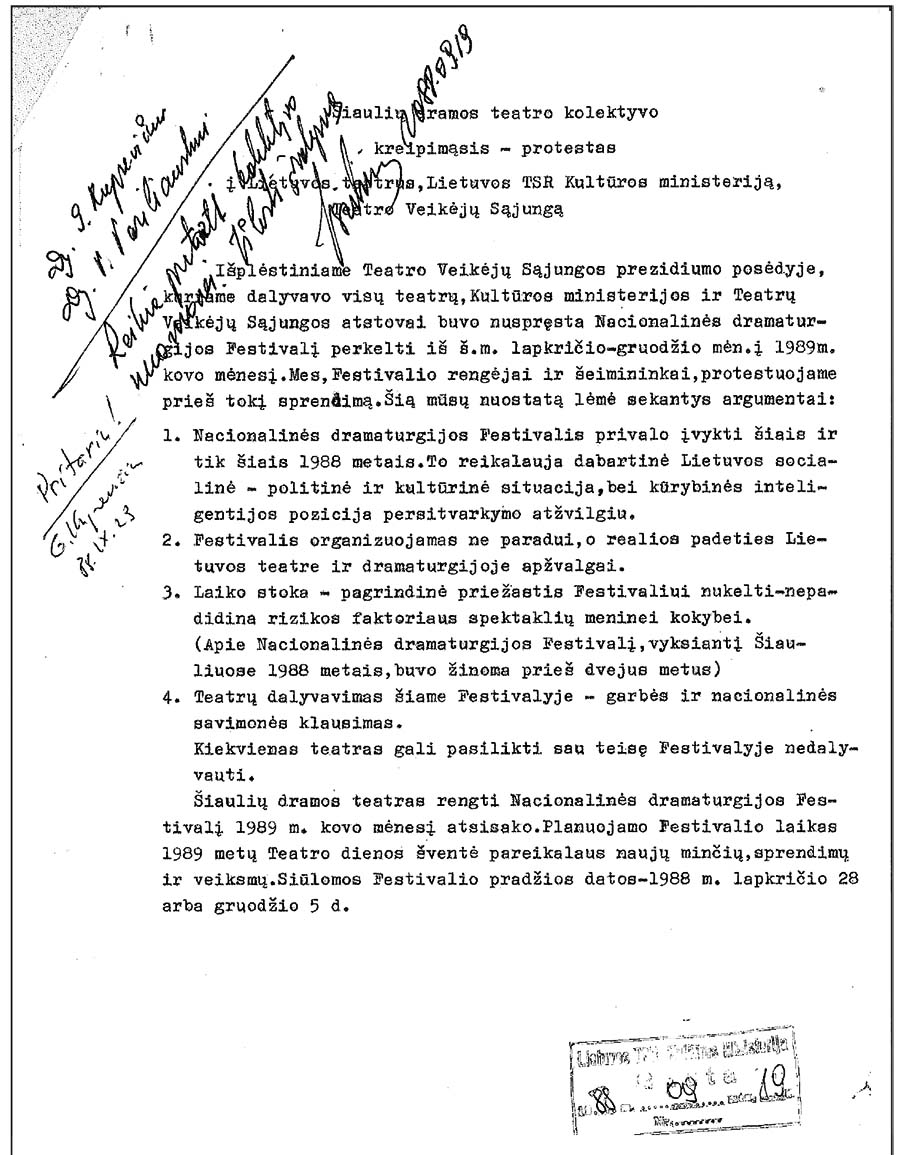

Điauliai Drama Theater “Protest-Appeal”. Gytis Padegimas explained the circumstances behind the handwriting on the document: “’Pritariu! (I approve!)’ was written by then Deputy Minister of Culture Giedrius Kuprevičius. ...The names written at the top [above Kuprevičius’s name] are those of Ministry of Culture Theater Department employees who had apparently been instructed to address the protest, and they, fearing to take responsibility, appealed to the deputy minister. Kuprevičius, being himself a man of culture, wrote, ‘I approve!’ and the festival was held in the fall.” (Lithuanian National Literature and Art Archive, Vilnius. File 342, Folder 3876, p. 4). |

|

Điauliai

Drama Theater Company Protest Appeal to

In the announced meeting of the

presidium of the Union of

Theater Professionals, in which representatives of all theaters, the

Ministry of Culture, and the Union of Theater Professionals

participated,

it was resolved to postpone the National Drama Festival

from November-December of this year to March of 1989. We, the

organizers and hosts of the Festival, protest this decision. Our

protest

is based on the following arguments:

The Điauliai Drama Theater hereby refuses to hold a National Drama Festival in March of 1989. To plan a Festival for the 1989 Theater Day holiday would require new ideas, proposals and activities. We suggest an opening date for the Festival of November 28 or December 5. |

| Điauliai Drama Theater Protest-Appeal, translation. |

Immediately Padegimas, along with thirty-two members

of his Điauliai drama troupe, drafted a tersely worded “Protest-

Appeal” stating that their drama festival “must take place this

year and only this year.” Dated September 19, 1988, the protest

argued that the planned festival would advance needed change

at a key moment: “The current social, political and cultural conditions

in Lithuania, along with the position of the creative intelligentsia

with respect to issues of reform, make it necessary.” Some of

the protest’s language was insolent: “The festival is being

organized not as an empty ceremony, but as an appraisal of

actual conditions in Lithuanian theater and dramaturgy.” And

some was defiant: “The Điauliai Drama Theater hereby refuses

to hold a National Drama Festival in March of 1989.” Holding

the event immediately, the dramatists said, was “a question of

honor and national consciousness.”7

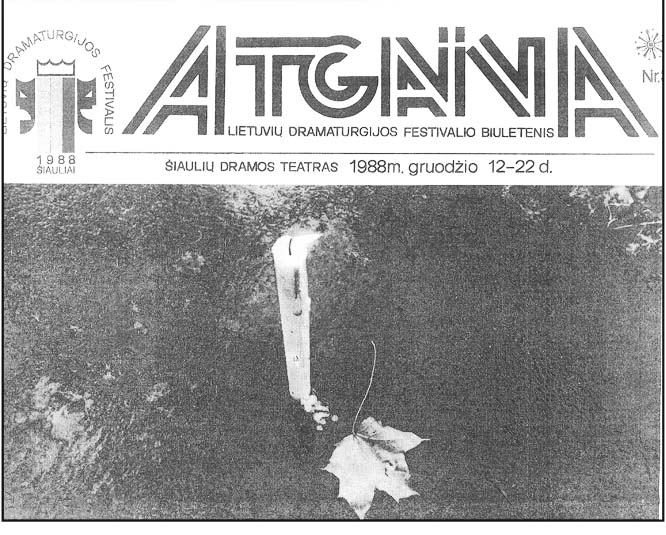

Thanks in part to an irresolute Kremlin then undergoing one of its most stunning periods of upheaval under Gorbachev, and in part to LTSR Deputy Minister of Culture Giedrius Kuprevičius, who had the courage to write “Pritariu!” (I approve!) above his signature on the submitted protest document,8 the Điauliai festival went forward, acquiring in the process its politically evocative name. The success of the Protest- Appeal no doubt awakened Lithuanian cultural workers to new possibilities for civil disobedience and exposed weaknesses in the previously impermeable policy boundaries of the Soviet regime. On nine successive nights beginning December 12, 1988, nine Lithuanian plays were presented, followed on the tenth evening by a festival-closing public symposium entitled The Role and Tasks of the Lithuanian Theater in the Process of Cultural Rebirth. Each of the plays staged expressed some form of anti-Soviet protest or carried liminal messages about the captive position of colonized cultures under Soviet hegemony. Along with the evening performances, a daily program, Morning Reflections – lectures and discussions led by writers, artists and professors, essentially reopened the previously closed field of Lithuanian culture studies. And every night at midnight, actors from the plays returned to the stage to participate in Night Poetry, a series of exhilarating dramatic readings from works by classic Lithuanian poets. All of these well-attended and enthusiastically received events expressed the nation’s acute hunger for self-actualization in the period just prior to the demise of the Soviet Union.

|

Atgaiva Festival Bulletin, front page. Four issues of the festival newspaper were published and a total of 6,000 copies printed during the event. The Bulletin featured political articles, reviews, and reactions to both the Morning Reflections and Night Poetry sessions. |

A sense of the highly charged atmosphere of Atgaiva can be gleaned from a look at three plays that became noteworthy for different reasons during and after the festival: Čia nebus mirties (There’ll Be No Death Here) by Rimas Tuminas and Valdas Kukulas, Ţvakidë (The Candlestick) by Antanas Đkëma, and Katedra (The Cathedral) by Justinas Marcinkevičius.

Of special interest to Lithuanian-Americans and scholars of American literature is the work that was voted Best Drama of the festival, There’ll Be No Death Here, a play about sociopolitical conditions in rural Lithuania during the late 1940s as reflected in the life of folk-poet Paulius Đirvys (1920-1979). Đirvys, who produced simple verses rich in folkloric influences, is a revered figure in Lithuanian cultural history, but the approach to retelling his life taken in There’ll Be No Death Here is far from conventional. As a review of the December 19 performance explained,

The conception of the creators of this drama is to tell about the life journey of the poet Paulius Đirvys, though we won’t find much here in the way of biographical facts or the presentation of data. ... Rather, in a poetically subtle way, the inner resistance of the young artist is revealed. For that purpose, excerpts from Jack London’s Martin Eden – which by the way was one of Paulius Đirvys’s favorite books – are put to good use.9

The typed minutes of the festival committee’s awards meeting reveal that There’ll Be No Death Here was the only play nominated for the event’s Best Drama Prize and was confirmed for the award in a unanimous vote of the eight-member prize committee, securing an honorarium of 2,000 rubles for coauthors Valdas Kukulas and Rimas Tuminas.

While it’s fascinating that there was so little doubt about which play was best among a number of well-received productions, it’s also worth noting that parts of the winning play were not written by its Lithuanian coauthors, but by an American writer who happened to be strongly socialist in his political outlook. Long passages from Jack London’s 1909 novel Martin Eden are quoted at key moments in the drama, and London’s highly autobiographical title character is a frequent presence on stage, becoming one of the play’s central tropes and most expressive elements.

Making much of the fact that Martin Eden was one of Đirvys’s favorite books, Kukulas and Tuminas first drew parallels in temperament between the Lithuanian poet and the American fiction writer and then, in effect, merged the two artist figures in meaningful ways. Considering the extent of the Lithuanian play’s debt to Martin Eden, one could argue that the Best Drama award presented to Kukulas and Tuminas for There’ll Be No Death Here also comprised a transnational tribute to Jack London.

London’s text and characters enter the play early. An evocative opening monologue from an elderly woman who had been Đirvys’s first love fades to a flashback of the village school at Vilkoliai, where in 1945, at the age of seventeen, she had met Đirvys, “a young blond man with a scar on his face . ... in a military uniform with a row of medals on his breast.”10 This reminiscence is interrupted by the entrance of “a very elegant lady,” Ruth Morse, the title character’s love interest in Martin Eden, who silently crosses the stage and exits. Ruth is followed on stage by “Martin Eden and his friend, an old sailor.” The sailor, an invention of the primary Lithuanian scriptwriter Tuminas, assumes the voice of London’s narrator and relates an account, translated almost verbatim from the final pages of London’s novel, of Martin Eden’s decision to drown himself at sea. The opening sequence clearly establishes, along with the play’s biographical intent, a literal analogy between the lives, loves and deaths of its central figures, Đirvys and Eden.

Martin Eden’s second appearance on stage, occurring in Act Two, asserts a relation between Eden and the aspiring young writers of a late-1940s Lithuanian village. The act opens with a monologue in the Vilkoliai library by Kostas Mildinis, a local official who had sided with fascists and worked for Hitler’s gestapo during the war. He later joined a band of Lithuanian nationalist partisans, only to eventually surrender his weapons and accept “the correct way of life” among the “heroic people” of the Soviet Union. Mildinis’s monologue, which glorifies Soviet rule, ends with his forced removal from the play. As the stage directions indicate, he is “pushed behind the wall with gaping cracks in it. These cracks are his last window to the world.” In essence, he represents the complex political dilemmas of mid-century Lithuania, a small country alternately subjugated by the large aggressor nations to its east and west.

With little transition, Mildinis is supplanted on stage by a scene adapted from London’s novel: “Like some vision, Martin Eden and his friend Brissenden descend into the library through the door on the right.” What follows is a soliloquy, originally given by Eden himself in chapter thirteen, but now spoken by Brissenden to Martin. “You wanted to write and you tried to write, and you had nothing in you to write about,” says Brissenden. The gist of the passage is that Eden had embarked as an artist before understanding “the essential characteristics of life” and that he needs more knowledge and experience before continuing. What the audience therefore witnesses is a process whereby painful historical realities (personified in the former nationalist partisan turned Soviet ally) are banished and replaced with a nascent artist figure.

After Martin and Brissenden depart, “The local writers burst into the village library with great excitement” to have a long discussion about the role of young poets in Soviet Lithuania. Their idealistic declarations – that the region’s “apprentice writers” must develop their talents for “the good of our dear socialist fatherland,” that “literature and art must flourish on every collective farm,” and that “all Young Literary People of Soviet Lithuania pledge themselves to write one short story about collectivization or five-year construction projects” – are standard platitudes of the Stalinist era and would have been recognized as such by the play’s 1988 audience.

The audience would also have noticed that the two character groupings in this part of the play – Martin Eden as described by Brissenden, and the young Lithuanian writers – share the trait of artistic immaturity. The juxtaposition exemplifies how the figure of Eden, along with London’s prose descriptions, is used by the playwrights not only to develop the Đirvys character through association, but to distill and comment on the political environment that formed him, a setting and discourse in which Lithuanians would recognize analogs to their national and personal histories.

Later in Act Two, the violent destruction of “bourgeois” books by Soviet officials sets up Martin Eden’s third appearance in There’ll Be No Death Here. This dynamic scene has several powerful elements. First, as the military officials destroy the Western books in the Vilkoliai library by violently chopping them up with axes, the play’s chorus thunderously intones the State Anthem of the Lithuanian SSR, including a line that was later deleted as part of the late 1950s de-Stalinization campaign, “Stalin leads us to happiness and prosperity.” In response, a “frightened teenage girl,” the lover of Đirvys, “begins to recite contemporary poetry, trying to drown the musical background.” In what is in effect an open cultural battle, the Soviet anthem dominates, but the “motif of the folk song” lingers, with the eradication of literature providing the physical action throughout.

The folk song then changes to the “Mexican” tune used in the play to signal each of Martin Eden’s entrances, and while tension is still high, “through a door in the plaster wall enter Martin Eden, his friend Brissenden, and an old sailor.” This time the dialogue is from chapter thirty-two of London’s novel, beginning with a presentation from Brissenden to Martin: “Here is a book, by a poet. Read it and keep it.” Essentially, Brissenden’s act signifies the appreciation rather than obliteration of art, the process of restoring reverence for what had just been desecrated by the Soviets in Vilkoliai. But the conversation comprises several ideas, including Brissenden’s claim that “one can’t make a living out of poetry,” his advice to Martin to leave Ruth behind to return to the sea, and the assertion that Martin is wasting himself by prostituting beauty “to the needs of magazine-dom.” All the while, Ruth’s voice is heard backstage, repeating, “I cannot love you, I cannot love you.”

So, while the first half of this diptych bluntly renders the aesthetically destructive effects of axe-wielding Sovietism, the second implies distinct forms of ignorance and philistinism associated with capitalism. Brissenden counsels his protégé on the way to live genuinely – letting beauty be your end, renouncing money, fame, and love, if necessary. For Martin, however, artistic integrity matters less than winning Ruth. At this point in his development as depicted by Tuminas, a false romantic ideal also associated with capitalism desensitizes Martin to the significance of art and culture, a significance actually felt more strongly by the teenage Lithuanian girl from Vilkoliai, who opposes barbarity with poetry.

The play concludes with another appearance by Martin Eden, this time preceded by a pair of juxtaposed speeches, the first of which is a discourse on Soviet patriotism from the director of the Vilkoliai library. The director’s monologue, read from a sheaf of official newspapers, is a forced recitation made in the presence of “aggressive and threatening” district officials. The vapid, cliché-ridden sermon about “the sunny life of Soviet nations in the land of Stalin” is described in the stage directions as “a meaningless dance filled with fear.” As the lecture devolves into absurdity, a Woman in Black enters and seizes the platform, speaking “in an entirely different tone.” A representative of realism and truth, she gives graphic accounts of horrific wartime atrocities in rural Lithuania, narrated “in an entirely different key from what the newspapers write.” When she exits, the mood among the audience of stunned Young People is one of “impending disaster, of some menacing premonition.”

This paralysis is broken by the appearance of the play’s chorus, among which are a Lady Teacher and Gentleman Teacher, who encourage the teenagers to “dance and laugh.” As the teachers carefully demonstrate dance technique and etiquette in a brave attempt to cheer the village youth, the Mexican melody begins, Ruth Morse’s voice is again heard from behind the stage, and Martin Eden enters with the elderly woman from the first act, who “listens to Ruth’s voice as if these were the words she uttered in her youth.” The exchange between Ruth and Martin, transcribed from London’s chapter thirty, conveys a commitment to art that had been lacking in Eden’s previous appearances.

But the words of Ruth and Martin are interrupted by the offstage shouts of an approaching group of men, overpowering the musical motif of the Mexican song. Next is the revelation that brings into focus the play’s calculated synergy of Lithuanian and American elements. As the play’s text explains,

The men [presumably Soviet thugs] approach Martin Eden, arrest him and strip him. His former sailor’s uniform is brought in. After changing into it, Martin Eden starts to speak in the words of Đirvys.

At this point, the audience fully realizes that Martin Eden has been Đirvys’s surrogate, played by the same actor, that the play has been simultaneously about both men, and that Đirvys, speaking through Eden, has been a significant presence on stage. The play’s text underscores the hard-to-miss point that the author of Martin Eden and the author of Đirvys’s letters coalesce. The voice of Đirvys explicitly instructs the audience: “Read Jack London’s Martin Eden – That’s me, Paulius.”

A sense of how There’ll Be No Death Here contributed to Gytis Padegimas’s stated goal of “analyzing the national consciousness” in a new era is contained in reviews of the production, many of which mention the play’s inventive uses of Martin Eden. Gediminas Jankus declared,

We rejoice that the authors of the play There’ll Be No Death Here have embraced the process of national renewal. The production tells openly and sincerely about postwar Lithuanian rural life, about the atmosphere of demagoguery that then prevailed there, which crushed more than one true artist.11

Another critic, Irena Aleksaitë, was more specific about the means by which “renewal” was advanced:

The personality of the poet Paulius Đirvys was reflected through the recent war-torn period and through excerpts from the novel Martin Eden, which were vividly associated with the life and destiny of the Poet.12

|

| Scene

from Čia nebus mirties (There’ll Be No Death Here).

Tiesa, March 4, 1989. Dovydas Mackonis photo |

It’s worth noting, however, that in the text of Martin Eden, the artist’s novel-ending suicide is caused mainly by the spiritually destructive influences of market-oriented society, and Tuminas’s script does not ignore this fact. The play’s Lithuanian characters and elements expose the soul-crushing effects of Stalinism, while its American elements explicitly disparage the spiritual effects of capitalism. Only the first half of this equation, however, seems to have registered with Lithuanian drama critics in December 1988. At the Atgaiva festival, the process of looking to the West and to Jack London’s life for cultural and political inspiration, and the process of making this play the festival’s leading and iconic work, required both a glossing over of the fact that Jack London was an outspoken socialist and a somewhat selective interpretation of Martin Eden.

Moreover, the acceptance of an American artist as an avatar for a local cultural icon reflects the idealism of the revolutionary period that led to Lithuanian independence. Within the audience’s twin embrace of Đirvys and London, for example, we glimpse the mindset behind the appeal of the Sŕjűdis political movement, which combined a Western outlook and reverence for artistic expression with anti-Soviet resistance, as famously embodied in the figure of its leader, Vytautas Landsbergis, a music professor.

But while the coupling of political and artistic expression will always have efficacy, it can produce oversimplifications. The visceral appeal of Čia nebus mirties at the moment of Atgaiva, along with the responses of reviewers who emphasized its anti-Soviet elements but did not acknowledge its anti-capitalist elements, reflects the eagerness with which Western cultural models were being embraced, suggesting an uncritical acceptance of especially American influences at the beginning of the post-Soviet period. Had this fine play been performed a decade or two later, it would certainly have been interpreted in more balanced and complex ways, with more acknowledgment of the oppressive effects on the artist of capitalist class relations and consumer culture.

More than the play itself, the play’s reception reflects a national mood that passed quickly after independence, but that does not make There’ll Be No Death Here any less valuable as a document from which several insights can be drawn. First, the fact that Đirvys was a great fan of Martin Eden – and that Kukulas and Tuminas saw spiritual likenesses between the two, and therefore between Đirvys and Jack London – adds up to a significant compliment for the American writer. The unanimous Best Drama Award for There’ll Be No Death Here, given by a prize committee that certainly knew London to have espoused socialism, also constitutes a tribute to the American writer’s legacy. Of greatest significance, however, is the fact that the spirit of Martin Eden did not simply travel well cross-culturally; it resonated strongly enough to be accepted as an emblem of Glasnost-era national feeling in the first Soviet Republic to declare its independence.

Another Atgaiva play, Antanas Đkëma’s two-act Ţvakidë (The Candlestick) warrants attention for its faithful representation of a second distinct point of view within the late 1980s movement for cultural-political independence. The Candlestick is a transparent allegory in which a family drama in a midtwentieth century Lithuanian village stands for the historical drama of the nation during the Soviet occupation. In keeping with its Glasnost-era presentation, the message is essentially a hopeful one, suggesting both reconciliation of previously opposed political factions and the imminent liberation and resurgence of local traditions and values, accomplished through the expulsion of outside, non-Lithuanian cultural influences.

The action takes place in “a corner of the sacristy” of a ransacked church in a rural Lithuanian village. Holy objects – candles, small icons, sacred images, books, and wooden boxes – are in evident disarray on the sacristy floor before “a dust-covered altar.”13 From the play’s opening moments, two religious items in particular – a heavy silver ţvakidë (candlestick) and a small rűpintojëlis (statue of lamenting Christ) – are invested with significance as relics that reflect the Christian character of local culture and the currently oppressed state of that culture.

Agota, an elderly woman, and Liucija, a soft-spoken sixteen-year-old girl, enter the desolate sacristy, where they have come secretly to pray on a summer Sunday morning. In the background, the church organ is heard; Liucija’s twentyfour- year-old brother Kostas, a man whom “pain has made rebellious,” furiously plays dissonant airs, alternately an improvised Bach toccata and sacred melodies, “sometimes like a saint, at others like Satan.”

The dialogue between the two women conveys grim circumstances: The church pastor, Liucija’s uncle, had been arrested several months earlier for hiding a written document in the church sacristy – we assume a political declaration of some type – that the arresting authorities “did not like.” Until a new priest arrives, praying in the church has been forbidden by the same authorities.

Liucija’s father Adomas, the family patriarch, described as “a tall, muscular man” whose countenance is “wrinkled with lines of grief,” enters the church looking for Liucija and is informed by Agota that the girl has just had a vision of the arrested pastor, Adomas’s brother, wearing a torn cassock. As Agota further reveals, there is a general belief in the community that Kostas, Adomas’s son, is the one who informed on the pastor and betrayed him to the authorities. Adomas’s other son, Antanas, is politically involved in a very different way: he is the real author of the writing for which the pastor was arrested. Responding to Agota’s persistent questioning, Adomas discloses that, in the previous two weeks, terror has reigned in the parish: eighteen people have disappeared, “apprehended during the night.”

Adomas sends Liucija home with Agota, leaving him alone in the sacristy for a monologue in which he sorrowfully addresses his absent brother. He then calls out to Kostas, who stops his organ playing and appears before his father. Speaking in general innuendos about spirituality and moral responsibility, Adomas conveys the suspicion that his son is the informer:“Don’t you think we should be humble before eternal things?” For his part, Kostas counters his father’s “theological lecture” defensively and defiantly, implying that Adomas is an overbearing father. When Kostas takes up a heavy silver candleholder from the sacristy floor and threatens to use it to smash the stained glass window, Adomas reacts with “quiet severity,” ordering him to relinquish the candlestick.

Twenty-two-year-old Antanas enters the scene panicstricken with the news that the pastor has been taken from prison and killed, gunned down in the forest amid a grove of pine trees. Antanas also reveals that he is the author of the document for which the pastor was murdered. Kostas quickly accuses Antanas of cowardice for not coming forward earlier, but Antanas explains that the delay was part of a plan. His uncle believed strongly that “the hour would come” to claim authorship of the document and counseled him to await instructions. “I thought that if I told the truth now I would be a traitor,” he says, adding that the pastor had approved of his writings and intended to use them as the basis of “future sermons.”

When Adomas and Antanas exit the scene, Kostas is given a monologue that reveals a view of his inner conflict as one between loyalty to “blood” and loyalty to “logical thinking.” After he exits, the ghost of the pastor enters the sacristy. Dressed in a tattered cassock, the “white-haired sixty-year-old” immediately picks out the rűpintojëlis that had been left there by Adomas, “smiles contentedly” as he examines it, and returns it to its place. Act One closes with the pastor seated alone before the altar, reading aloud a litany of prayer and scripture with clear political implications: “I will rise, mend the rent clothing, and with candle in hand, walk the long road. And the people will follow me. ...”

In the play’s second act, the spirit of the murdered pastor is a strong stage presence, conversing in a special way with the young Liucija, the only character who is able to see and speak directly with him. It is the evening of the same Sunday when Liucija, carrying a bouquet of wildflowers, returns to the church, where the organ playing of Kostas is still heard in the background and her uncle awaits her, holding forth in the same tone with which Act One had ended: “And the people will follow me, and this procession will be called The Hymn to the Almighty.” Liucija and her uncle speak informally and affectionately, the pastor describing the sensations of his death in the forest, of the pain he felt and “the smell of the moss” beneath the tall pines. For her part, Liucija declares that speaking with the pastor’s ghost has brought her into a new world, a better world where intuitive, spiritual knowledge is more concrete and valid: “I am happy that I’ve begun to live, for I was only half alive and half dead. Now I am truly alive.”

Agota suddenly enters, relieved to find Liucija but unable to see the pastor and confused by Liucija’s apparently distracted conversation. She brings the good news, however, that “it seems the end is near.” At the same moment, the pastor informs Liucija that her brother Kostas will soon experience “a beginning.” After the pastor exits, walking through a wall, Agota explains that a battle has begun at the borders and the current occupiers are fleeing the country. For the rest of the play, the thunder of artillery and sounds of destruction are heard in the distance.

At this moment, Liucija is less concerned with the historic power struggle going on around her than with the sudden need to speak with her brother, the traitorous Kostas. Agota fails to understand: “What can you expect from a person who has betrayed his relatives to play the organ – sometimes like a saint and at others like Satan?” In answer, Liucija repeats her uncle’s prophecy: for Kostas, “the beginning is near.”

Liucija calls to Kostas and the brother-sister confrontation in the sacristy ensues. Immediately, the girl relays several messages: their murdered uncle has been listening to Kostas’s playing; he spoke of a new beginning; these words were “meant for” Kostas. The skeptical brother answers that she is delirious and their uncle is dead. The girl begs Kostas to somehow feel the pastor’s pain and experience the smell of the forest moss. A decisive exchange follows when Kostas dismissively replies that “Imagination runs in our family: The father is a sculptor, one son a musician, the other a poet, and the daughter, a madwoman.” To which Liucija answers, “and the musician plays because he is a murderer.” Kostas’s agitated reaction prompts Liucija to reach for the candlestick and brandish it in self-defense. Her blunt words – that the church is Kostas’s only refuge because he is a collaborator – bring about a momentary softening in her brother. “Put down the candlestick. I won’t hurt you,” he replies before launching into a monologue that expresses the desolation of his inner landscape, a place where “the sky is totally black and there are no stars.” Liucija is sympathetic toward her brother, but sees only two choices for him – either take up arms to help expel the country’s enemies or join those enemies and escape into exile. Kostas asserts that there is a third way that remains a secret.

His meaning is manifested in the next scene, where the symbolic candlestick becomes a fratricidal murder weapon. The remainder of the play is dominated by a long exchange between Kostas and his brother Antanas, who returns to the church bearing a rifle to be used against the country’s occupiers, not all of whom are leaving peacefully. “Come with us,” pleads Antanas, “there’s a rifle for you too.” After an emotional “family meeting,” in which the patriarchal Adomas and Antanas remind Kostas of the “simple truth” of their mutual bond, Kostas seems ready to rejoin the family and convert politically. As he admits to Antanas, he hates himself, but both hates and loves his brother. At the suggestion of Antanas, the reconciled siblings proceed from the sacristy to the church, where they will “kneel together at the great altar.” Antanas leads the way and Kostas follows with the candlestick, which he says he intends to place before the altar with lighted candle as a symbol that “some object must unite the two of us.” Moments later he returns to the sacristy alone, having, in the words of the Pastor’s ghost that awaits him there, “deceived both Antanas and himself” with a murder that only increases his stark alienation.

In Đkëma’s romanticized universe, Antanas and the Pastor, both of whom are killed by traitors to the national cause, live on. But the play does not clarify just what, other than the religious devotion and mystical faith of the principal characters, the national cause consists of. The content of Antanas’s political manuscript is never revealed, and the final words of the murdered Pastor, though shot through with optimistic conviction, remain vague about the play’s larger historical themes:

They are still shooting, but we do not hear it. We are going somewhere else. ... The outsiders are fleeing from our land. Our people are winning. I believe that the outsiders will not return. Ever. And our life will not be just a life for ourselves. We will live also in the memories of our loved ones. In their hearts. We live. Happy and real. And that is the truth. Let it be. Let it be.

Only once in the play is it mentioned that the “outsiders” the Pastor refers to are being overcome by a military force “from the West,” and that the role of Lithuanians who take up arms in this conflict is to “help those from the West expel the enemies of our land.” While this is enough to suggest a historical basis for the process in the experience of Lithuania during World War II (when the country was alternately occupied by the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany), a specific context is never developed, and the warring forces are never actually identified. For these reasons, it becomes difficult to argue that this drama is a recapitulation of World War II history, especially since the Pastor’s valedictory prediction that the “outsiders” will never return to Lithuania had already been contradicted by the time Đkëma wrote the play in New York in 1955.

The intentional ambiguity and imprecision of the play’s setting permit, if not compel, the recognition that, despite its resemblance to events of the 1940s, this play is not really about the World War II era, but about the end of the Cold War. This end was still quite far off when Đkëma wrote the play, but when the play was staged at Atgaiva in 1988, it was actually happening. Like There’ll Be No Death Here, Đkëma’s play uses the 1940s only allegorically, as a superficial template on which to graft messages about the here and now. Once this is acknowledged, it becomes apparent that, whatever forces act upon Lithuania from outside, the important thing is how the microcosm of the Lithuanian family reacts from within, living as they do in a time and place of great historical change.

|

| Scene from Ţvakidë

(The Candlestick). Rimanta Krilavičiűtë as Liucija,

Edmundas Leonavičius as Kostas. Điauliř naujienos, February 22, 1989. Juozas Bindokas photo. |

The Candlestick was directed by the host of Atgaiva, so we would expect it to accord well with the festival’s objectives and to somehow be “about” the Glasnost-era present rather than a remote past. We also have an unusual type of evidence that suggests how it did so. For a theater director to publicly expound on the significance of a production before it takes place is a rare thing, but that is what Gytis Padegimas did by authoring an article that appeared in the newspaper Điauliř naujienos on December 4, six days before the play’s December 10 premier and seventeen days before its presentation on December 21 as the final play of the Atgaiva festival.

A striking aspect of the article, titled simply “Antanas Đkëma’s Ţvakidë”, is the clear danger Padegimas discerns in the uncritical acceptance of Western or American values at the moment of national rebirth. In the life, death, and art of Đkëma, Padegimas derives an implicit warning about the effects of Americanization on the Lithuanian spirit. He begins with an unattributed quote from Đkëma, probably from his published letters:

We have lost life in Capital Letters. We rest comfortably in the embrace of lower case life. We have souls of silver, hearts of silver. Can it really be that the heart pumps only turbid water?14

But the passage would mean little without Padegimas’s interpretation of its relevance to the historical moment:

This painful sigh, coming from the lips of Lithuanian writer, director, and actor Antanas Đkëma in his Golgotha of exile in Germany and the United States, is now urgent for us who today rise and defend our land, our language, and our souls. “Don’t you think that when it comes to the everlasting things, we should be ashamed of ourselves?” This by no means simple rhetorical question plagues the characters in The Candlestick, permeates the author’s entire body of work and becomes one of its primary catalysts.

Having placed Đkëma’s artistic subject matter firmly within the ongoing struggle to “defend” Lithuanian cultural heritage, Padegimas then discusses Đkëma’s life and death as an exile, noting that the author “left Lithuania in 1944 for Germany and the United States and died in an auto accident in Pennsylvania in 1961.” The circumstances of Đkëma’s death give Padegimas the opportunity to comment on American culture:

The painful opposition between “the promised land” of “those Americans” – who “increase and multiply, who have skyscrapers, baseball, Republicans and Democrats, the Atlantic Charter and the atomic bomb, the borough of Brooklyn, and who play the ponies, put their feet on the table, and ready themselves to triumph over oppression,” and between, on the other hand, the “great misunderstood loneliness” – acquires drastic form, defines the self, and often ends in violence.

It is apparent that Padegimas, with unusual foresight, recognizes dangers in the coming tidal wave of cultural influence from the West, even as he leads the liberation of his country’s theater from control by the East.

Another key assertion, however, is the connection Padegimas makes between Đkëma’s sudden rehabilitation as an artist and the current political atmosphere:

Đkëma has returned to longed-for Lithuania during this summer of rebirth. ... Đkëma, who for so long has been a bogeyman for us, comes back as a major artist – honest and merciless toward himself so that he can bear witness to much national history . ... Perhaps not all of his witnessing is objective, perhaps it is overly emotional and extreme to us, but it is honest.

Padegimas here delights in the opportunity to resurrect a previously banned artist, but he seems acutely aware that his play may not receive a universally positive reception. He reveals that he anticipates critical censure for three specific shortcomings in Đkëma’s art: lack of objectivity, sentimentality, and a form of extremism that can be assumed to derive from the play’s mysticism and religious fervor. The article therefore closes with a plea on behalf of Đkëma for tolerance and openmindedness toward a perhaps unpopular viewpoint:

So let’s listen to the bloodstained words of the poet. And for ourselves – who live in the days of renewal for the nation and for humanity – decide what is important and what is, perhaps, less meaningful. Let’s be tolerant and receptive to the talented poet, all the more so because he asks so little.15

In the end, if Đkëma’s work asked little, it also received little from the reviewers and theater colleagues whose criticisms Padegimas had anticipated. At the meeting of the prize committee on the day after the festival, Đkëma’s play was nominated for only one award, the last of ten prizes offered, for Vidmantas Bartulis’s musical score. When a secret vote was taken to decide whether to actually confer this minor award, only a simple majority was required, but Đkëma’s play was still effectively shut out. Six of eight committee members voted against the prize – a result suggesting possible resistance either to the play’s inherently religious ideology, or to Padegimas’s public attempt to shape its political meaning as a caution against Western influence, or to both. In its final official act, however, the Atgaiva Prize Committee requested that the Lithuanian Cultural Fund grant an award and citation to “Điauliai Drama Theater Director Gytis Padegimas” for “the nurturing (puoselëjimas) of Lithuanian drama.”

While the works by Đkëma and Tuminas-Kukulas were new to the Lithuanian stage, Atgaiva also resurrected and transformed previously produced plays in order to put them to new uses. The December 15 performance of Justinas Marcinkevičius’s Katedra (Cathedral), shows how a canonical drama with an already standardized critical interpretation could be adjusted to new political priorities.

Cathedral, the third work in the author’s acclaimed trilogy of plays about Lithuanian history, is set in Vilnius at the end of the eighteenth century. During this period, Lithuania and Poland, brought to near ruin by the greed of feudal lords, were in economic and political crisis. The land and wealth of the country had been seized by more powerful neighboring empires. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania had lost the last vestiges of its statehood and sovereignty, and the country stood at the dawn of a new historical epoch. The philosophy of the French Enlightenment was spreading across Europe, sending out shock waves of revolutionary activity.

To analyze and derive meaning from this situation, Marcinkevičius chose representative historical material connected with the life and work of the celebrated Lithuanian architect Laurynas Gucevičius (1753-1798), a talented and culturally concerned artist whom Marcinkevičius saw as an apt expression of the strength of Lithuanian national creativity during the period. Gucevičius, the designer of the Vilnius Cathedral, is often described as the father of Lithuanian architecture. The play depicts his struggle to create a Lithuanian national identity by rebuilding the Vilnius Cathedral as a shrine to progressive humanitarian cultural ideals.

By implicitly comparing the architectural achievement of the cathedral with its creator, Marcinkevičius found a workable means of recasting the original meaning of the structure in a new historical context. “With the building of the Vilnius Cathedral,” the author explained in 1971,

the efforts of the nation to preserve its highest ideals were realized. The drama of the architect Laurynas is the story of an artist who does not find inspiration in the society of his time – from which he might have found support for his social and artistic activity.16

The history of the cathedral’s construction, imagined alongside the events of the 1794 Polish-Lithuanian uprising against Tsarist Russia, is Marcinkevičius’s historical framework. The play’s dramatic intensity derives largely from the effects of aptly employed factual detail from the period’s ideological struggles, closely intertwined with the main character’s imagined inner life.

Marcinkevičius’s attempt to locate the precise moment when the national ideal took shape is especially significant because it is set against the background of a corrupt and degenerate state at a decisive moment of social change. The playwright sifts a time of existential crisis for the Lithuanian nation, searching in the actions of his characters for evidence of essential human traits, elemental strength, and creative depth. The dramatic contradictions of the moment, along with the progress of the culture at large, are poetically crystallized in the inner life of Laurynas.

But throughout the play, Marcinkevičius is actually less concerned with historical minutia than with universal questions about the causes and consequences of political resistance to oppressive regimes – questions of particular moment during both the play’s period of production in the late 1960s and its Glasnost-era re-presentation twenty years later at Atgaiva. When the play was first published in 1970, certain anti-Soviet elements would have been recognizable even though nearly two centuries separated the historical action from the contemporary scene. Marcinkevičius’s inclusion of a derisively presented character identified simply as a “spy” – a figure who appears at public gatherings and clumsily interrogates political demonstrators with questions like, “Who said there is no justice here? What is your name? Where do you live?” – should be understood as an intrusion of the author’s present on the historical past, forging a link between the eighteenth-century context of feudalism in Lithuania and a counterpart Soviet reality that famously relied on citizen surveillance to preserve its authority. Another obvious reference to Soviet life comes when Marcinkevičius humorously describes his townspeople displaying a behavior that became both automatic and proverbial within the socialist economy of scarcity: “When I see a crowd of people, I get in line behind them without thinking,” observes one Vilnius resident.

Despite the play’s elements of political dissent, Soviet-era literary criticism was able to circumscribe its meaning within parameters of socialist ideology, under which the primary forces in the conflict were figured as opposed social classes. Essentially, Soviet critics pigeonholed the drama as a representation of the inevitable destruction of the feudal system, followed by the advent of the more progressive historical force of the proletariat. Jonas Lankutis, writing in 1977, saw the play as a “heroic folk drama,” portraying resistance by peasants to “the slavery of serfdom.”17 Conforming to the norms and expectations of Marxist analysis, Lankutis and other Soviet critics reduced the play to a “philosophical dramatization,” a depiction of the class war in which the central historical question was “whether Lithuania would be able to rise from the ruins of its feudal past.”18

At Atgaiva in 1988, however, the play was suddenly permitted to address the question of whether the country would be able to rise and recover, not from its feudal past, but from its Soviet present. Dalia Gudavičiűtë’s review of Panevëţys director Saulius Varnas’s production in the December 17 Điauliai News leaves no doubt that the play was widely understood as a parable about the current cultural context of anti-Soviet selfassertion. Gudavičiűtë’s opening sentence: “It seems to me, and has for some time, that educated theatergoers, those responding to the ‘wave of Rebirth,’ will soon be sending the editors a list of statements that they no longer want to read in reviews,”19 places the play squarely in the political realm. About Cathedral, the statements Gudavičiűtë deems suddenly undesirable include any vestiges of previously standard criticism: “that the play is being staged for a third time in the Lithuanian theater, that the Panevëţys theater is now undergoing a crisis, and that this is the first production of Saulius Varnas since he left the Điauliai Theater.” The critic is elated that matters of greater historical consequence have freed her from mundane reportage: “So I’ve just written all of this at the very beginning, and for the rest of this late-night review, let’s try to forget such phrases.” The review is obviously the work of someone who feels caught up in social change and feels compelled to acknowledge this fact.

Aware of and responsive to an altered atmosphere, the critic is therefore more interested in the fact that the play was staged in “contemporary dress and a contemporary setting,” and that this was “necessary,” she explains, “for the purpose of showing the presence of an eternally recurring situation” in the play’s action. Although the implication is that some current form of the 1794 rebellion is now happening, the critic probably has in mind a more general set of imperatives involving all moments of socio-political revolution, a reading equally justified by the play’s text but further heightened by the modern-dress production element.

Not surprisingly, Gudavičiűtë identifies specific parallels between the final decade of the eighteenth century and the period of Glasnost. At times it is actually unclear whether the critic is commenting on Varnas’s production or on the world outside the theater walls. For example, Marcinkevičius’s play opens with the return of Laurynas from four years of study in Paris, a moment that is afforded interesting significance:

The “absurd environment” here referred to, an atmosphere that prompts the critic to seek the terms for current types of political betrayal, shows Gudavičiűtë doing just what the updated production asks its audience to do: equating the sociopolitics of the past with those of the present. Once this happens, the critic can publicly use the play to carry out a task only recently made possible: the asking of fundamental questions about the daily lives of Soviet citizens. Her comment on Laurynas’s relative freedom of movement becomes a comment on the still-formidable restrictions on travel under the Soviet regime:

And about Paris. How can it be, at the close of the twentieth century, that a Lithuanian audience seated in a theater can be so responsive to the possibility of studying in Paris and traveling to Italy to view masterpieces? In this case, they cannot identify with the characters and experience their emotions. The action on stage begins to be understood as absurd. But when the thought occurs that for the artist this situation has been held to be normal for ages – then the absurdity of our own existence becomes clear.

Two decades after the Atgaiva festival, Padegimas recalled that the event moved audiences to overcome or redirect their fear of political self-expression. In a fascinating way, Gudavičiűtë’s review confirms that this actually happened:

Perhaps the timid guffaw of the audience during the sentencing of the dissident insurgents is actually that familiar laughter that accompanies freedom from fear? Perhaps the audience expressed the desire to mock itself for its fear that soon someone among them would be officially called ‘a disturber of the peace’ or an ‘irresponsible element,’ and that all would end with ‘a solemn public penalty,’ and afterward we would all have to ‘face the music’ and ‘dine on the sausage and beer of the magistrate’?

Padegimas also claimed that the events of his drama festival had become “political rallies” and that they inspired the nation. The drama critic corroborates these assertions as well by articulating the effects of a cultural event – the viewing of a performance of Cathedral – in terms that predict the political liberation that followed:

It’s said that we sometimes need to free children from crushing fears through permission to speak of and internalize them in realistic terms. Perhaps it’s likewise necessary to free grown men and women from their own contrived fears... Just in time, because these emotions are very useful later, when viewing a television broadcast.

What makes the foregoing passage striking and interesting is its turn to sarcasm, a turn that displays hostility toward current conditions and current media discourse that are no longer tolerable. This is explicable as a function of the play’s apparent power to inspire social change. As Laurynas declares, “We are in contact with the roots of Lithuania, proclaiming the rebirth of the homeland,” a revolution the purpose of which is to “awaken the people and revive the state.”21

At the same time, Varnas’s Cathedral contains a strong cautionary message about anti-Soviet revolution and all revolutions. Its assertions that “only through pain do we give birth to children, the homeland, and freedom” and that “homeland” and “liberty” may become “accursed words that bear no fruit”22 seem to predict the chaotic loss of ideals that followed swiftly upon national independence in 1990. The end of the play seems to foresee and warn that revolutions devour their children. Speaking to the cathedral itself, Laurynas acknowledges that the physical and ideological structure could become “a pantheon or a mausoleum,”23 structures that both function as shrines to heroes or ideals that are dead.

The full story of the Atgaiva festival has not been told in any article or book, in either the United States or Lithuania. In fact, the festival background I have related in this article is probably the most detailed historical account to date. But these observations are only a beginning, a sampling of what may be gleaned from further study of the festival through the lens of culture studies. Having begun to look deeply into the event, I sense that Venckus, in the letter quoted at the start of this article, could have gone further in celebrating Atgaiva, an event he himself had participated in (playing the title role in Viktorija Jasukaitytë’s Ţilvinas under Padegimas’s direction in one of the festival’s important plays) and no doubt remembered well. Perhaps the fact that Venckus had to remind the Điauliai mayor of what happened at Atgaiva is the best evidence of the extent to which it has been neglected.

Viewed in hindsight, the Atgaiva festival not only registered cultural protest; it also contained important forewarnings of the painful disillusionment that immediately followed the restoration of Lithuanian autonomy. The dearth of previous research on Atgaiva is likely a direct result of this disillusionment. Within the intense debates among theater critics about the meaning of the festival, the outline of later and current debates about the over-idealization of both local and Westernderived cultural standards is clearly discernible. In some ways, the rebirth of Lithuanian culture on the dramatic stage that took place at Atgaiva continues to be reenacted on the nation’s political stage – with similar implications.

If for nothing else, Atgaiva deserves to be remembered for the electric charge it sent through the Lithuanian theater community. Two weeks after the festival, the headline of Lolita Tirvaitë’s article in the respected journal Literatűra ir menas (Literature and Art) conferred historic significance by referring to the event as “Ten Days that Shook Điauliai.”24 Tirvaitë’s obvious echoing of Ten Days that Shook the World, the famous bookmby American communist John Reed about the advent of the Bolshevik Revolution, was clever and ironic. Atgaiva not only “shook” Lithuania, but successfully subverted an obsolete Soviet regime in its dying days – the same regime Reed’s book had welcomed into existence in its first days. Tirvaitë captures the excitement and elation of the moment:

In Điauliai there was created something which we have only dreamed about at the end of previous festivals that have left only the bitterness of unfulfilled hopes... For ten days we felt ourselves spiritual aristocrats, free and independent men and women brought together for the purpose of creativity... And the plays have given us the much longed-for strength of hope.25

Studied in its entirety as a unified narrative, the Atgaiva festival may be understood as a declaration of Lithuanian cultural independence from the Soviet Union that preceded the country’s political declaration of independence by some fifteen months.