Copyright © 2013 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Editor of this issue: Elizabeth Novickas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2013 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume

59, No.3 - Fall 2013

Editor of this issue: Elizabeth Novickas |

Sigismund Augustus’s Tapestries in the Context of the Vilnius Lower Castle

IEVA KUIZINIENË

IEVA JEDZINSKAITË-KUIZINIENË is an art historian who studies early artistic textiles in Lithuania. A professor at the Vilnius Academy of Arts, she is the author of two monographs on Western European tapestries in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Abstract

This article is dedicated to the analysis of the tapestry collection

of the Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland Sigismund

Augustus – a collection that played an important role

in the representational life of the rulers and which both his

contemporaries

and today’s art textile researchers agree was one of

the most stylish and opulent in all of Europe. The main focus of

this research is on the links between the ruler’s collection and

the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania. Earlier authors,

most of them from outside Lithuania, have not even considered

the possibility of such links. Nevertheless, by synthesizing

Lithuanian and international scientific research from various

fields and different periods related to this particular theme,

and by critically analyzing material from earlier publications

that can now be supplemented with new facts, the history of

the collection’s development and its role in the representational

life of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth is revealed in a

completely new light.

The residences of European monarchs

played an important

role in their respective countries’ political, social and cultural

life, contributing to the state’s international image. In the Grand

Duchy of Lithuania, this role was played by the residence of

the Lithuanian grand dukes in the Vilnius Lower Castle, which

had existed, it appears, by the reign of Gediminas, who ruled

the Grand Duchy between 1316 and 1341. Vestiges of each

ruler remain, but those of the Gediminid-Jagiellonian dynasty

must be given credit for the castle’s most significant enhancements.

The palace, which was rebuilt and expanded during

their reign, became an important state administrative center,

strengthening the image of Vilnius as the capital city and representing

the country in the European monarchical community.

This was where the traditions of public etiquette and customs

were formed, along with the international image of the ruler’s

court. The residence’s representational function – which would

include the palace architecture, the rulers’ collections, public

ceremonials and celebrations – was particularly important.

In the scope of this article, only one aspect of this representational function will be analyzed, namely, the tapestry collection of Sigismund Augustus. The value of the collection and the veil of secrecy that surrounds the history of its acquisition have interested researchers from various countries since the first half of the nineteenth century. This research, however, has been greatly complicated by the fact that a majority of the tapestries from the collection are missing. No comprehensive, detailed inventories have survived, nor many documents relating to the commission, presentation, or storage of the tapestries. Its history remains somewhat mysterious.

Research on the collection’s origins and its role in the ruler’s court concentrated exclusively on the Wawel royal residence. This article synthesizes previous research and supplements it with archival material compiled by Lithuanian and international researchers from various fields and periods, and on historical research on the Vilnius Lower Castle and the collections of the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, along with court traditions, the rulers’ travels, and events in their personal lives. In order to reconstruct the tapestry collections, literary sources were also analyzed, especially panegyrics dedicated to important events in the lives of the rulers of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, such as weddings and coronation ceremonies, where much attention went into the decoration of the ceremonial rooms. Of note are Stanisůaw Orzechowski’s Panagyricus nuptiarum Sigimundi Augusti Poloniae Regis (Panagryric on the Nuptials of Sigismund Augustus, King of Poland, 1553) and Maciej Stryjkowski’s O poczŕtkach, wywodach, dzielnoúciach, sprawach rycerskich i domowych sůawnego narodu litewskiego, ýemojdzkiego i ruskiego (On the Genesis, Accounts, Valor, Knightly and Domestic Affairs of the Famed Peoples of Lithuania, Samogitia, and Ruthenia, circa 1578). A translated excerpt of this text follows this article.

In light of the new information, established historical and art research treatises are now becoming an object of discussion and revision.

Early Tapestries

The kings, dukes and other nobles of Northern and Central Europe started taking an interest in tapestries during the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. Even though it is commonly said that the most important purpose of these textiles was to serve as insulation for the cold medieval castle walls or as room dividers, it is more likely that the representational and decorative purpose of tapestries had always been important. Much like the narrative Italian Renaissance painting cycles, tapestry sets depicted topical political events and glorified monarchs and generals, who were likened to historical or mythological heroes or gods.

The popularity of these art works also grew due to their ease of transportation and multitude of uses. Tapestries covered interior walls and window and doorway niches, and insulated and decorated rulers’ battlefield tents. They were also used to decorate facades, balconies, and streets during religious festivals or other celebrations.

The first information about Western European tapestries in the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania is found in documents chronicling the lives of the Jagiellon family, its court, and its art patronage traditions. In written sources, Andreas Cricius (Andrzej Krzycki, 1482–1537) mentions a display of tapestries at the wedding of Sigismund the Old and the Italian noblewoman Bona Sforza in 1518. He described the ceremony in his panegyric Epithalamium divi Sigismundi Primi regis et inclytae Bonae reginae Poloniae (Epithalamium to the Divine King Sigismund I and the Illustrious Queen Bona of Poland, 1518). The author wrote of tapestries and textiles shining with gold thread, hung upon the walls of Wawel Castle in Kraków.

On the day of his death in 1548, Sigismund the Old owned 108 tapestries (not including those from Bona Sforza’s dowry).1 However, there are no comprehensive inventories that could be used to determine the structure of the tapestry collection from the times of Sigismund the Old and Bona Sforza. It is believed that many tapestries could have been later removed from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Some ended up in the dowries of Sigismund the Old’s daughters and Sigismund Augustus’s sisters.2 Several of Sigismund the Old’s armorial tapestries were sold at a 1673 auction in Paris following the death of John II Casimir Vasa.

Only one historical text has been found to support the speculation that tapestries decorated the Palace of the Lithuanian Grand Dukes during the reign of Sigismund the Old. This is a document cited by Daiva Steponavičienë in her research on life in the Lithuanian ruler’s court, which indicates that in 1517 Lithuanian Grand Duke Sigismund the Old sent eminent representatives on sleds covered with cushions and carpets woven with gold and silk thread to meet the envoy of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (1508–1519), Sigismund von Herberstein (1486–1566).3

Early Documentation of Sigismund Augustus’s Collection

There is no doubt that the most valuable items in the royal tapestry collection in Lithuanian and Polish history were acquired by Sigismund Augustus. This is why it is so surprising that almost no archival documents remain about the orders for this collection (contracts, accounts, correspondence, etc.). This may be attributed to the strained financial situation of Lithuania and Poland and their rulers and the enormous costs involved in forming such a collection, costs that Sigismund Augustus preferred remain unknown. This supposition can be supported by an order in his will, directed to his sister Anna Jagiellon (1523–1596), to thoroughly destroy all the listed documents after his death. Evidence of the ruler’s efforts to hide these expenses is also found in the report of the papal nuncio Bernardo Bongiovanni in 1560, prepared after visiting the Palace of the Grand Dukes in Vilnius, where it is written that “treasures give him an immense amount of pleasure, and one day he showed them to me in secret, as he does not wish for the Poles to discover that he has spent so much on them [...]”4 It is believed that part of the collection was commissioned in Vilnius, not Kraków, which may be why the documents have disappeared, along with other documents from the Vilnius residence.

The first known source in which the tapestries of Sigismund Augustus are described is a panegyric by Orzechowski, a student of the universities of Padua, Bologna and Rome, Panagyricus nuptiarum Sigismundi Augusti Poloniae Regis, dedicated to the wedding of Sigismund Augustus and his third wife, Catherine of Austria, the daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I (1503–1564), published by Andrzej Ůazarz in 1553.5 The author, who described the ceremony, mentions large figurative textiles that amazed the guests at the wedding feast. In the large reception hall (today known as the Senators Hall), six tapestries from The Story of Noah were on display; in the hallway there were five textiles from The Story of Moses; while in the newlyweds’ bedroom there were eight tapestries from The Story of Paradise.6 One of them hung above the rulers’ bed.

Orzechowski’s text, full of inspiration and epithets, not only allows us to identify the textiles that decorated the castle during the wedding, but also conveys the impressions this collection left on the political and cultural elite who witnessed it. The commentary clearly reveals both interest in the visual narratives and rapture at the masterful work of the weavers and artists. The textiles are described as opulent, unusual, and not like those seen in the palaces of other rulers. An interesting and intriguing comment made by the author conveys the observers’ reactions to the textile narratives, particularly that of the set The Story of the First Parents, which decorated the newlyweds’ bedroom. Orzechowski called it Paradise Bliss, and in his praise of its naturalistic portrayal of the figures, the author highlights their nudity:

In the first textile, hanging above the head of the matrimonial bed, we can all witness the image of our ancestors’ bliss, where they are depicted nude, with their male and female parts completely uncovered. At the time, their nudity made such an impression on those who set their eyes upon it, that the men smiled while gazing at Eve, and the women – at Adam.7

An interesting detail is that the nudity of both Adam and Eve was later hidden by vine-leaves woven and embroidered onto the original textile. These modifications were most likely made during the time of Sigismund Vasa (1566-1632), a result of the influence of the Counter-Reformation.8 The reactions of the feast’s guests in assessing the tapestries’ depictions are also noted by Zbigniew Kuchowicz, who analyzed the legal circumstances and customary freedoms of women in Lithuania and Poland. As an illustration of the conservative attitudes of Poles, he mentions this event:

... when Sigismund Augustus hung tapestries acquired in the West in the Wawel, it was scenes depicting naked people from the Bible’s Book of Genesis which aroused the greatest interest of the observers, as they had never before seen such images.9

Kuchowicz most likely had in mind the naturalism and size of the figures.

There are some inaccuracies in Orzechowski’s descriptions of the tapestries. For example, he describes the singular The Story of the First Parents textile as three separate textiles, and the tapestry Noah Speaks to the Lord is mentioned twice as separate textiles.

Orzechowski’s accounts lead us to believe that in 1553 the following tapestries hung at Wawel Castle: The Story of Paradise (The Story of the First Parents); The Story of Noah; The Story of Moses (lost); and The Story of the Tower of Babel.10 Orzechowski does not mention the tapestry depicting Cain and Abel with the caption Egrediamur foras (Let’s go out to the field). In the opinion of the art historians Mieczyslaw Gćbarowicz and Tadeusz Mańkowski, it must have been acquired later, because it is of a different stylistic appearance.11

The five-piece set, The Story of Moses, Orzechowski described has been lost. Until recently, it was believed that three tapestries from this set were taken to Rome in 1633 by the Polish envoy Jerzy Ossoliński (1595–1650) and presented as a gift to Pope Urban VIII (pope from 1623 to 1644).12 They have not been found in Rome, and research by Maria Hennel-Bernasikowa has revealed that Ossoliński could not have taken these tapestries there. She notes that The Story of Moses, woven with gold thread, that is mentioned by Orzechowski does not appear in either the inventories of Stanisůaw Fogelweder, drawn up on September 29, 1572, nor in the lists drawn up in Tykocin on September 9, 1573. The latter list mentions a ninepiece set of The Story of Moses without gold thread. In the author’s opinion, the set mentioned by Orzechowski with gold must have disappeared from the collection while Sigismund Augustus was still alive, sometime between 1553 and 1572.13

Thus, while it is known which tapestries from which particular sets decorated Wawel Castle for the wedding of Sigismund Augustus and Catherine of Austria, it is not clear where these tapestries were beforehand or whether all the tapestries they owned were displayed for the occasion.

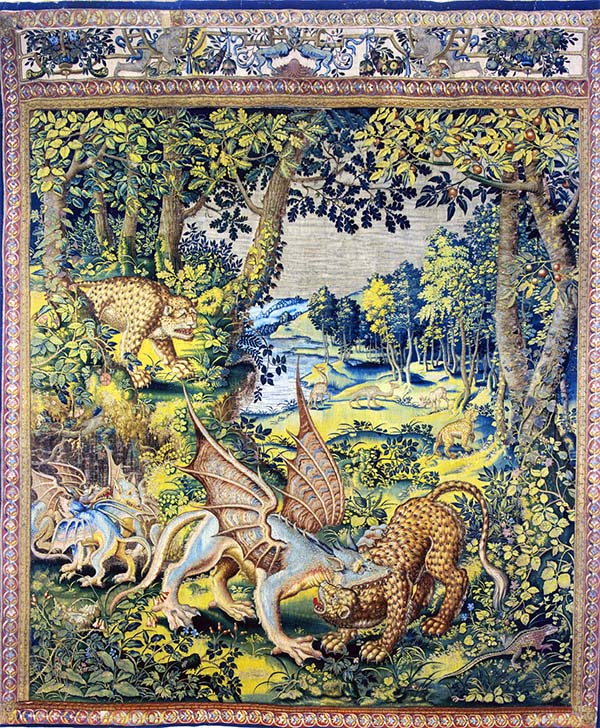

The opinions of authors who have studied when the first commissions were made by Sigismund Augustus and what sets they included vary. Many agree that the tapestries described by Orzechowski in 1553 were woven earlier, between 1548 and 1553. In the opinion of Marian Morelowski, during the wedding at Wawel not only must the tapestries described by Orzechowski have already been in place, but also the verdures with animals on a landscape background (see illustration on page 48). The author bases this claim on the stylistic similarities between the animals depicted in the verdures and those in the biblical textiles.14 Gćbarowicz and Mańkowski differ on this point, asserting that the verdures and textiles featuring coats of arms were created later than the biblical tapestries.15

The Financing of the Collection

Since there is a lack of archival information on the acquisition of Sigismund Augustus’s textiles, any further assumptions regarding their commission must rely on indirect information and be based on an analysis of historical facts concerning the lives of the rulers and their financial circumstances.

It is unlikely that Sigismund the Old would have dared to commission an expensive series of artworks towards the end of his life. And since his son, Sigismund Augustus, was merely the Grand Duke of Lithuania and had only the relatively meager income of a Lithuanian ruler’s treasury at his disposal, such expenses would have been beyond his means. But there is little doubt that a commission of such grand scale would have coincided with important events in the life of Sigismund Augustus. In consequence, one can suppose that the tapestries were acquired between 1548 and 1550, once Sigismund Augustus had ascended the throne of the King of Poland and was preparing for the official presentation of Barbara Radziwiůů (1520–1551) or on the occasion of her coronation. This chronology of events is given by Gćbarowicz and Mańkowski as well. In their search for sources to confirm the date of commission of the textiles under discussion, the authors base their conclusions on such facts as tapestries from the set The Story of Adam and Eve were being sold in Augsburg in 1549. This was discovered from correspondence that year between Catherine of Austria, who later became the third wife of Sigismund Augustus, and the Habsburg palace’s tapestry-master Jhan (Ihan) de Roy.16 Catherine of Austria charged him with the task of purchasing tapestries from Flanders for three rooms, at a cost of a thousand guldens. In the court of Ferdinand I in Prague, Jhan de Roy was granted a passport allowing him to freely travel to Antwerp. The purchased tapestries and canvases were to be delivered over “ice and water” to Innsbruck and transferred to Józef von Lamberg. Catherine of Austria also authorized Jhan de Roy to find out if it was possible to purchase tapestries for another four rooms and their cost, to bring with him a painted sketch of these tapestries, and to determine whether tapestries depicting Adam and Eve offered to her earlier were still for sale. She also asked whether it was possible to purchase them at a lower cost than was discussed. No knowledge exists on how these negotiations proceeded or what was bought or delivered. If Catherine of Austria had acquired the tapestry set The Story of the First Parents, and they were the same six tapestries identified as cum figuris ex veteri testamento in her dowry inventory, then these tapestries would have made the journey along with her to Kraków in 1553. However, at the time she was traveling to Kraków, The Story of the First Parents tapestry set was already hanging in Wawel Castle. The art historian Jerzy Szablowski doubts whether the tapestry set for sale in Augsburg can be connected to the early commissions of Sigismund Augustus. The author points out that there are no archival documents that mention Catherine’s purchase of the set. In addition, in his view, at least two sets would have to have been purchased at the same place and the same time: The Story of the First Parents and The Story of Noah. However, The Story of Noah was not for sale in Augsburg in 1549.17

|

| The Introduction of Adam and Eve (from the tapestry set The Story of the First Parents). From the workshop of Jean (Jan) Leyniers, Brussels. After cartoons by Michiel I Coxcie (Coxie), mid-seventeenth century, 350 x 230 cm. From the collection of the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania. |

After determining the collection’s value (in 1668, the collection of Sigismund Augustus was valued at two million auksinai or timpos),18 further efforts to specify the period of tapestry commissions investigated Sigismund Augustus’s income and his ability to raise credit. Many historians have concluded that he could not have possessed such a sum in either cash or liquid assets. In the view of a majority of researchers who have studied the tapestry collection, he could have looked for credit abroad or in Gdańsk. One of the largest and most successful trade and banking houses in Gdańsk at the time was that of Dom Loitzów, which carried out its financial operations in Antwerp via a local intermediary, the Wrocůaw merchant Melchior Adler.19 Sigismund Augustus had gone to Dom Loitzów on more than one occasion. An interesting piece of information was recorded by the German chronicler Reinhold Heidenstein (1553–1620), who wrote that Sigismund Augustus took out a loan of 100,000 talers for a set of textiles featuring a unicorn. However, the collection’s researchers believe that Heidenstein must have confused the textiles, since the palace inventories show no mention of any such set. A unicorn is featured in several of the ruler’s tapestry compositions, but not as the main figure; it appears only in the background. Just which tapestries Heidenstein had in mind when mentioning the unicorn remains unclear.

In order to place the sum of 100,000 talers in perspective, Sigismund Augustus sought, via his delegates, a loan of the same size before going to war over Livonia in 1559. In that instance, he was apparently not successful in getting a loan in Gdańsk.20

New archival material published by Hennel-Bernasikowa forces a reassessment of these long-held hypotheses with respect to the ruler’s assets. The most important is a letter from Sigismund Augustus dated January 1, 1561. In this missive, he writes that he owes Jakub Herbrot, an Augsburg citizen serving as the ruler’s advisor, and Herbot’s sons, “for certain treasures and gold and silk woven tapestries,” the total sum of 79,404 florins and six pennies, which must be paid in three equal parts during the next three years. The payment is to be made in timber products dispatched to Gdańsk.21 This and other letters also reveal that the commodities were various intermediate timber products sourced from the massive Augustavas Forest and the clearing of forests in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and other lands. Economic transactions of this kind, as the documents reveal, had been conducted for a long time. After 1549, it was under the control of Jan Kopf (d. 1565), a citizen of Gdańsk and Kaunas.22

It is, nevertheless, uncertain whether the sale of timber was the sole financing for the purchase of tapestries. At the time the debt note was signed, the biblical tapestries, and perhaps some of the others, were already part of the ruler’s collection. Ryszard Szmydki offers an interesting hypothesis in his analysis of alternate options for financing the collection and repaying whatever loans may have been incurred. He discusses the ruler’s income from trade in Lithuanian and Polish agricultural products in markets in the Netherlands, especially in Amsterdam. It was precisely when Sigismund Augustus was commissioning the Brussels tapestries that European demand for grain increased. In 1557, merchants from Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Brussels even appealed to the King of Spain, Philip II, to intercede with the Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland so that a large amount of grain could be transported from Eastern Europe as soon as possible to the famineravaged Netherlands, Portugal, and Andalusia.23

In addition to the already mentioned financial sources, we should also pay attention to the increased income coming from the Grand Duke’s lands after implementing the Wallach reform in 1547. Archival sources note this increase:

The King is Lithuania’s heir and its absolute ruler. […] From this province, the King usually received somewhat more than 100,000 talers income [copy No. 2 states this as 200,000], but now, having removed much forest and measured the land after an increase in population, and because tributes are no longer paid in goods, the King receives somewhat more than 500,000 talers a year.24

Regardless of the various hypotheses, two facts are certain: a part of the tapestry collection already decorated Wawel Castle in 1553, and on January 1, 1561, Sigismund Augustus borrowed 79,404 florins and six pennies from Herbrot for purchasing tapestries and other treasures.

Other Archival Sources and Connections with the Vilnius Lower Castle

In the context of this information, a document from the treasury account books of the court of the Lithuanian Grand Duke concerning Sigismund Augustus’s acquisition of artworks – dated January 14, 1546 and published by Rűta Birutë Vitkauskienë in 2006 – is very interesting. A passage from this document reads:

The themes of the mentioned paintings are characteristic of the tapestries of that time. However, it is of note that, among the listed paintings, we have The Creation of the World and Noah’s Ark, or The Great Flood. The subject matter is directly related to the tapestries from The Story of the First Parents and The Story of Noah. Note also the fact that Germania is the historic name of the Netherlands,29 so a more correct translation would be “to some Netherlander” rather than “to some German.” The value of these artworks is also telling. It would have been impossible to purchase a high-quality painting for the sums mentioned. But cartoons of future tapestries, called petits patrons or patrons au petit pied, went for similar sums. These are small sketches showing the primary compositional elements, so that the client could get an idea of the overall design. In these works, the most important aspects were the image, the compositional scheme, and the proportions and silhouettes of separate elements. The coloring would be limited to a watercolor wash of certain elements or a list of the dominant colors (red, green, yellow, etc.).30 By way of comparison, we can mention the sum the chancellor of the Council of Brabant paid Jan de Kempeneer on January 15, 1541 for two tapestry cartoons: eighteen florins.31 We can also estimate the size of this “painting” on the basis of an analogical drawing, which, it is believed, was prepared at the same workshop that created the cartoons of Sigismund Augustus’s verdures. The drawing, currently held by the British Museum in London, measures 284 x 525 mm.32

When we consider this archival information in conjunction with other known historical facts about the personal life of Sigismund Augustus and his tapestry collection, we can safely conclude that his first tapestry commissions were made in the Palace of the Lithuanian Grand Dukes in Vilnius. This interpretation of the information presented would also comply with Szablowski’s claim that The Story of the First Parents and The Story of Noah sets were commissioned at the same time.

In developing this hypothesis, it is interesting to speculate about the future of the other listed sketches. Perhaps Sigismund Augustus did not authorize them? On the other hand, it is believed that the tapestries mentioned in the ruler’s will, described there as portraying Muses, are those called Allegories of the Virtues in the cited treasury document, especially since the author of the cartoons for The Story of the First Parents and The Story of Noah is considered to be Michiel I. Coxcie (Coxie, 1499–1592), who created the Allegories of the Virtues cartoons in the same period.

Tadas Adomonis noted the fact that the 1548 inventories of the Vilnius rulers’ palace mention the tapestry set The Story of Adam and Eve.33 While the author unfortunately did not cite his sources, archival sources confirm that in 1548 tapestries hung in the Palace of the Lithuanian Grand Dukes in Vilnius. For example, an entry on February 23, 1548, concerning the upholstery of the Lower Castle’s audience-hall walls and benches, mentions that:

...for the iron nails used for attaching the textile during Lent [?] to the walls and benches and elsewhere – six gentlemen advisors [?] were given five auksinai in the farrier’s room of the Vilnius Lower Castle.” 34

However, these sources do not shed any light on the tapestry’s themes.

Various other records also testify to the existence of textile art in the Vilnius Lower Castle residence. On June 28, 1551, the court tailor, Martynas, and six assistants prepared the castle halls, the Vilnius Cathedral, and four other Vilnius churches for the Requiem masses mourning the death of Barbara Radziwiůů.35 On August 30, 1552, by order of the ruler, his embroiderer, Sebaldus, was sent from Kraków to Vilnius, together with the Italian gemstone engraver Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio (1500–1565).36

The opulence of the rulers’ palace in Vilnius during the reign of Sigismund Augustus can be surmised based on the 1560 accounts, mentioned earlier, of the papal nuncio Bongiovanni, which describe the ruler’s collection in Vilnius:

The King has many wonderful items; among them in Vilnius he has 180 small and large cannon of very fine craftsmanship (His Majesty is very proud of them) and is planning to have more cast. The Poles are very unhappy about this, saying that he is robbing the kingdom and amassing treasures in other locations […] The King has twenty personal suits of armor, four of which are exceptionally grand, and especially one suit, which has exquisitely engraved and encrusted silver figures portraying all of his ancestors’ victories against the Muscovites […]37

In addition to furniture, including those pieces brought from Naples by his mother, the letter describes rubies, emeralds, and diamonds, and the clothing adorned with these gemstones. The author of the letter makes this comment on the collection:

The riches Sigismund Augustus kept in the Vilnius palace depository included 15,000 pounds of unused gilded silver, as well as fountains, timepieces with figures the size of a man, organs and other musical instruments, and a globe with all the signs of the heavens proportionally depicted. Also mentioned in the letter were thirty horse saddles and bridles that were beyond comparison in their opulence. Bongiovanni also wrote that His Majesty employed rare specialists for each of the arts. For example, gemstone and engraving work was done by Giovanni Giacomo39 from Verona, the French crafted his artillery, a Venetian was hired for carving work, and a Hungarian served as an excellent lute player;40 and so on for all the arts. Bongiovanni added this comment:

This level of opulence should not come as a surprise, knowing that the last Jagiellon often resided in Vilnius. Statistics bear this preference out: before 1555, the ruler of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland spent almost 51 percent of his time in Vilnius, in 1556–1558 he spent 68 percent of his time in Vilnius, and during another four-year period (1559–1562) he spent as much as 81 percent of his time in Lithuania. At the time, the Lithuanian capital played the most important role as the residence of the Jagiellons. Viewing Vilnius as the ruler’s primary residence is supported by the scale of construction work carried out on the Lower Castle starting in 1544. New halls were added, serving as a separate, private residence for the young ruler. Sometime later, earlier buildings erected during the reign of Sigismund the Old were reconstructed, and the palace’s Renaissance closed inner-courtyard ensemble was formed.42

The evidence linking the first tapestry commissions with the official presentation of Barbara Radziwiůů in Kraków in 1549, or her coronation in 1550, lies not just in the period the textiles were commissioned, but also in documents regarding the painstaking preparation for these events. The details of Barbara Radziwiůů’s arrival in Kraków were discussed as early as August of 1548 by her cousin Mikoůaj “the Black” Radziwiůů (1515–1565) and Hetman Jan Tarnowski (1488–1561). As Mikoůaj Radziwiůů wrote, the desire was that “people would gather to greet the Queen at the border and all would progress differently than people expected.”43 Sigismund Augustus in particular made careful arrangements for the journey: he decided on an exact departure date (September 1) and ordered way stations to be readied to care for the horses and carriages. Lists of members of the entourage were also made, aiming for as many famous people as possible to accompany Barbara Radziwiůů.44

Roderigo Dermoyen’s Role in the Formation of the Collection

The first set to be commissioned by Sigismund Augustus was identified from Orzechowski’s panegyric. However, the panegyric only mentions the textiles that were displayed during the wedding ceremony. Research on the period the other textiles were commissioned has been influenced by two of Sigismund Augustus’s letters, presented on July 6, 1904 to the Art History Research Commission in the Academy of Science of Poland by Stanisůaw Cercha. Both bear the same date and origination (May 12, 1564, Knyszyn), and both are addressed to the treasurer of the Prussian lands and the castellan of Gdańsk, Jan Kostka (1529–1581). They make mention of Roderigo (Rodrigue, Rodrigo) Dermoyen (Van der Moyen) and matters related to him. In the first letter, written in Polish, the ruler appeals to Kostka, writing that he is sending Dermoyen to him:

our servant, so that having given the orders regarding those cortyn45 he should be sent back, as was discussed in Warsaw, and that he should go to every effort to manufacture them as soon as possible and dispatch them to him [Sigismund Augustus].46

In the second letter, written in Latin, Sigismund Augustus writes about the three-year delay in payment for his servant Dermoyen, a citizen of Lübeck, who has not received his annual salary of 100 auksinai that was to be paid from the treasury of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. It is indicated that this lapse occurred because Dermoyen was not present. The ruler orders Kostka to cover the 300 auksinai debt from the Prussian treasury (to include the salary for the current year), and to pay out the 100 auksinai without delay in future years.47

Based on these letters, which had until then been the only known archival material related to the commissioning of Sigismund Augustus’s tapestries, it was concluded that the second tapestry commission can be associated with Dermoyen, while the date of the letters indicates the possible time period of the commission. However, Dermoyen’s participation in the commissioning of the collections is not viewed the same way by all authors. Morelowski attributed both the figurative tapestries and the verdures to the first commission, while the grotesque and armorial textiles, according to the author, are from a later date and could have been delivered by Dermoyen between 1561 and 1564.48

Gćbarowicz and Mańkowski gave more importance to the role played by Dermoyen. In their view, it was not just the armorial and monogrammed textiles that appeared after the biblical tapestries, but also the verdures featuring animals. The authors even determined the transportation route taken. The agent would have sailed from Gdańsk to Antwerp and then gone on to Brussels. It is also assumed that Dermoyen would have taken colored and uncolored examples of ornaments with him on his trip to Flanders and tried to match the coat of arms and the ruler’s monogrammed compositions.49 However, these assumptions are not based on any sources, much like the authors’ claim that the verdure cartoons were commissioned by Dermoyen from Willem Tons after first discussing their design with Sigismund Augustus 50

|

| Dragon fighting with a Panther, one of the verdures from Sigismund Augustus’s collection. Brussels, circa 1555. Photograph by Stanisůaw. Michta. Copyright Wawel Castle, Kraków.. |

The German tapestry researcher Heinrich Göbel, who received the complete texts of both letters from Morelowski and published them in his work titled Wandteppiche, had another assessment of Dermoyen’s activities.51 According to Göbel, Dermoyen was both a weaver and a merchant, and had his main workshop in Lübeck, where he lived, as well as branches in Gdańsk or Malbork, which, upon the ruler’s order, Kostka had helped him establish. In the researcher’s opinion, Sigismund Augustus’s tapestries were woven there.

Szablowski52 acknowledges Dermoyen’s participation in the commissioning of Sigismund Augustus’s tapestries without associating him with any specific tapestries. Meanwhile, Anna Misiŕg-Bocheńska attributes even the latest figurative tapestries from The Story of the Tower of Babel, not mentioned by Orzechowski, to Dermoyen.53 Belgian scientist Jozef Duverger also examined this theme.54 Duverger’s research indicates that Dermoyen was the son of Willem Dermoyen, the renowned owner of the Brussels weaving workshop that was in active operation in the first half of the sixteenth century. He married Maria van den Hecke, who hailed from a well-known Brussels weaving family. Based on information in Polish literature, Duverger expresses surprise that Roderigo Dermoyen did not carry the title of ruler’s servant (servitor), as Pieter van Aelst did, who was the honorary weaver of Pope Leo X (1513–1521). The close ties Dermoyen had with the best-known Brussels weaving families led the author to assume that perhaps all of Sigismund Augustus’s tapestries were commissioned with his mediation.55

Hennel-Bernasikowa56 and Szmydki conducted more comprehensive research on Dermoyen’s role in the formation of Sigismund Augustus’s collection. Based on material collected by these authors, Sigismund Augustus signed a contract with Dermoyen on September 7, 1559. It is unclear precisely which gold and silk woven tapestries were commissioned at the time, but the sum of this commission was 12,000 florins and was to be paid out over three installments of 4,000 florins.57 Meanwhile, other entries from the inventory book of the court of Sigismund Augustus published by Hennel-Bernasikowa, which were made by the palace scribe Jakub Zaleski, relate specifically to black-and-white tapestries. On April 28, 1564, i.e., two weeks before Dermoyen was sent with the ruler’s letters from Knyszyn to see Kostka, an entry in this book states that he was paid 165 auksinai compensation for his journey from Lübeck to Knyszyn. The purpose of this journey was to order tapestries (opony) that, in the ruler’s opinion, needed to be manufactured in Germania inferiore (as has already been mentioned, Germania is the historical name of the Netherlands). Two years and three months later, on August 9, 1566, Zaleski records another payment: “By order of His Majesty the King, Dermoyen, a hired servant of His Royal Majesty – 200 auksinai. This money was intended for black-and-white tapestries (opon), as well as ‘for food.’” More information is given in a letter from the ruler addressed to Kostka, sent from Lublin and written a day after the payment, i.e., on August 10, 1566. Sigismund Augustus announced to the castellan of Gdańsk and treasurer of the Prussian lands that in accordance with the honorable agreement made with Dermoyen, black-and-white tapestries, manufactured and complete,

were delivered to us and presented to our depository. The first installment of the payment had already been made, and now he [Dermoyen] was to receive the remainder. He nevertheless feels cheated, since according to the contract, he was to receive a quarter short of three auksinai per cubit of textile. That is why he asks that he be paid three auksinai for each cubit.

The ruler indicated that he was immensely pleased with Dermoyen’s work and instructed Kostka to pay him all that he was owed, without delay and with no further discrepancy. On the other side of this document there is an inscription: Rodericus de 1314 florenis pro auleis. It is unclear what portion of his salary this truly large sum was meant to cover; but the commission was important, and there must have been a great number of black-and-white tapestries delivered by Dermoyen.58

Szmydki59 was more interested in analyzing the activities of Dermoyen himself. Based on the information given by the author, Dermoyen’s brother, Jan Dermoyen, owned a tapestry weaving workshop. Their nephews, Christian and Peter, were also weavers.

Dermoyen had established a financial enterprise with Pierre Bonfant in Antwerp in the mid-sixteenth century, an enterprise that received its income from capital turnover and rent. Based on information about the payments received by the brothers between 1552 and 1559, Szmydki draws the conclusion that the Dermoyen brothers, being experts in tapestry manufacture, acted as appraisers of the material value of tapestries being transported out of the Netherlands through the Antwerp customs office. Later, Dermoyen disappeared from Antwerp. It is known that in 1561 he sold an expensive set of tapestries woven in gold, silver, and silk thread, consisting of eleven textiles depicting the story of the Emperor Octavianus, to the King of Sweden, Erik XIV. The Swedish archives mention that at the time of the transaction, Dermoyen, originally from Brussels, was living in Lübeck. By 1570, The Story of Octavianus was already at the disposal of the brother of Erik XIV, John III of Sweden (Vasa) (1568–1592). According to his will, and together with the efforts of his son Sigismund Vasa, this set was later deemed the property of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

In summarizing the information presented here, it can be said that Dermoyen worked as a tapestry agent in the court of Sigismund Augustus from at least 1559 to 1566 and truly participated in the acquisition of the unidentified gold and silk woven tapestries and the now lost set of black-and-white tapestries. His involvement in the commissioning of the other sets remains a hypothesis. The letters that Sigismund Augustus sent to Kostka in 1564 do not indicate where Dermoyen was sent or which tapestries he acted as agent for. According to Hennel- Bernasikowa, after 1560 or perhaps even earlier, the ruler commissioned only black-and-white decorative textiles (completely uncharacteristic of his earlier taste), while the tapestry donated to Sigismund Augustus by Krzysztof Krupski, with the year 1560 interwoven, marks the date from which the ruler no longer commissioned any new tapestries.60 The fact that at least the verdures had to have been commissioned reasonably earlier and that they cannot be associated with the name of Dermoyen is confirmed by other facts as well: the small cartoon sketch (284 x 525 mm) kept in the British Museum in London,61 believed to be from the same period and the same workshop that created Sigismund Augustus’s verdures, is dated to 1549, which is soon after the first knowledge we have of the biblical set’s sketches.

Sigismund Augustus’s Last Commissions – The Black-andwhite Tapestries

The black-and-white tapestries are the last known tapestry commissions made by Sigismund Augustus. Based on various documents, Hennel-Bernasikowa tried to reconstruct the content of these tapestries. According to the author, they consisted of armorial drapery and were, as usual, not especially large. The initials SA (Sigismundus Augustus) were incorporated into the center. The textile’s border was white.62

The question arises as to whether these were, in fact, tapestries. Both Hennel-Bernasikova’s consultations with experts and my consultations with antique dealers in the search for tapestries for the interiors of the reconstructed Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania failed to produce any information about black-and-white tapestries. Hennel-Bernasikowa presents only one archival fact found among documents on tapestry weavers in the Netherlands. It indicates that in 1509 the regent of the Netherlands, Margaret of Austria (1507–1515, 1519–1530), ordered that a certain sum be paid to a Brugge weaver for a black tapestry bearing her coats of arms.

In this context, the tapestries illustrating the labors of Hercules, woven in 1565–1566 in the tapestry manufactory of Michiel de Bos in Antwerp, provide an interesting clue. According to Guy Delmarcel, the set, commissioned by the Duke of Bavaria, Albert V (1550–1579), consisted of thirteen large tapestries and ten oblong armorial tapestries and was woven using only two colors – dark blue and white.63 The date of their commissioning draws our attention, since it is close to when Sigismund Augustus commissioned black-and-white tapestries (1564 and 1566). Both commissions are known to have included armorial tapestries. The latest known colored armorial tapestries of Sigismund Augustus were created according to cartoons by artists from the circle of Cornelis Floris de Vriendt (1514–1575) and Cornelis Bos (1506/1510–1556) from Antwerp, while the dark blue-and-white tapestry sets for Albert V were created according to engravings by Cornelis Cort (1533–1578). The latter repeated the cycle of ten paintings that Cort’s brother, Frans Floris de Vriendt (1517–1570), created in 1550 for Antwerp merchant Nicolas Jongelinck.64 Also noteworthy is that Albert V was married to the daughter of Ferdinand I, Anna of Habsburg (1528–1590), who was the sister of Sigismund Augustus’s first and third wives. Knowing the precision of historical inventories, it would come as no surprise if the “black and white” colors of Sigismund Augustus’s tapestries would, in fact, have been dark blue and white.

The ruler’s attachment to black and white is also reflected in the palace tailor’s (believed to have been Sebaldus) report on all the jobs he had completed in the court over twenty-three years, i.e., from 1549 until the death of Sigismund Augustus. Alexander Przezdziecki published this report.65 The jobs were divided into four groups, each with a detailed description including the costs involved. Alongside the pieces created for the rulers Barbara Radziwiůů, Catherine of Austria, and Anna Jagiellon, pieces created for Sigismund Augustus were also described:

In 1560, I started work on items in Vilnius that I later finished in Warsaw, such as kobiercy [carpets] and room upholstery of black velvet and white velvet, embroidered in white and black silk. There were fifty-two such items for the walls [...].66

This is a significantly large number of embroidered pieces featuring only black and white.

This color preference of the ruler has been the subject of widespread speculation and the theme of romantic tales. Józef Ignacy Kraszewski wrote about them in his historic accounts, and this was how one aspect of the image of Sigismund Augustus, who dressed in mourning clothes from the death of his beloved Barbara until his own passing, was formed. Officially, the ruler no longer had to wear mourning clothes after 1552, an event that was marked in the Půock Cathedral during the oneyear anniversary of the death of Barbara Radziwiůů.

The papal nuncio Giulio Ruggeri, writing about his visit to the court of Sigismund Augustus in 1568, adds an interesting note:

The fact that the rooms in the residences of Sigismund Augustus were upholstered in black textiles is confirmed by records made in the inventory book cited above. On December 23, 1569, several days after arriving in Warsaw from Lublin, Zaleski notes: “For black baize. That day I paid for sixteen panels of baize, from Wrocůaw, black, for upholstering the benches and walls in the King’s rooms […]”68 Three months later, in a letter sent from Warsaw dated April 3, 1570, from Sigismund Augustus to Marcin Podgórski, one of the primary trustees of the so-called Tykocin treasures, there are instructions to urgently send black baize, because it is needed immediately. Draping rooms with black baize was commonplace during periods of mourning. Sigismund Augustus, arriving from Vilnius after the death of his father, met with his mother and sisters in a room upholstered in black textiles on May 26, 1548. However, during the period in question (after 1560), there were no compelling reasons for Sigismund Augustus to be in mourning.

Evidence for the Transportation of the Tapestries

The tapestries that hung at Wawel were covered and taken down most probably in 1559. This is based on the record entered by Zaleski in Kraków on June 6, 1559, indicating that on that day, two rolls of black baize for covering the tapestries and carpets were purchased, for which five auksinai and twenty- five pennies were paid (including the sewing work). The tapestries were soon taken down, but it is not clear whether they were transported to Vilnius or stored in the Vaulted Hall of Wawel Castle. A week after the record concerning their covering with black textile, on June 14, 1559, Zaleski made the following entry:

This sum was spent by Zaleski and five others, while following the ruler to Radom in two carriages packed with His Majesty’s sundry items and money. Afterwards, there are rather frequent mentions of various tapestry restorations, mending, and the hanging of related works in the Palace of the Lithuanian Grand Dukes.

It is believed that the transfer of tapestries and other treasures from the collection in Wawel and other residences to Vilnius – the most commonly frequented ruler’s residence – began immediately after the wedding of Sigismund Augustus and his third wife, Catherine of Austria, in 1553. For example:

The Krosno tapestry-textiles or wall upholstery (auleas telaes), eighty pieces, sent to Vilnius in 1553 were delivered in two carriages. They were brought by Tatar Baroszewicz. He was paid 343 auksinai and three pennies.70

Additional entries between 1559 and 1561 mention that tapestries were transported from Kraków to Vilnius and displayed in the palace halls. A note from February 27, 1560, mentions that on that day, one auksinas and fifteen pennies were paid for the mending of certain tapestries, some of which had become damaged from mold in the new vaulted hall in Krasnystaw, while others had torn while hanging for long periods. It was also written in regard to the same matter that one auksinas and twenty-eight pennies were paid to those who assisted Rapolas Vargravskis in hanging tapestries and handling the boxes.71

Another entry from the same year testifies that in 1560 unskilled hands and drivers carried textiles intended for the court of his Holiness the Royal Majesty from the carriages into a vaulted room. They were paid twenty-four pennies. On that same day, 110 kapas were returned to the worker Jostas for the nails which were used to affix the tapestries and upholstery, and he was paid six auksinai and twenty-eight pennies.72

An entry from August 8, 1561, mentions that, on that day, four of the ruler’s bedroom walls in the Palace of the Lithuanian Grand Dukes were decorated with tapestries interwoven with gold thread.73 Tapestries were also mentioned on October 8, 1562, as part of the dowry of Sigismund Augustus’s sister, Catherine the Jagiellon (1526–1583), who was marrying the Duke of Finland, John III. The list was compiled at the Vilnius palace. The seventh item in the list enumerates the textiles in the princess’s room: eight small and large decorative textiles illustrating the story of David’s son, Absalom, using the “printed” method, and other wall textiles described in less detail; one floor rug, without edging, of green ornamentation on a black background; thirty yellow Turkish rugs with various types of edging; one large, yellow Turkish table rug; a large Lithuanian floor rug for the room, and other textiles, baize, velvet, etc. These textiles must have been at the Palace of the Lithuanian Grand Dukes when the inventory of her dowry was made.74

Strykowski’s Description of the Tapestry Collection

Julia Radziszewska’s article75 relating to a sixteenth-century description of unknown tapestries found in the versed chronicle by Maciej Stryjkowski, O poczŕtkach, wywodach, dzielnoúciach, sprawach rycerskich i domowych sůawnego narodu litewskiego, ýemojdzkiego i ruskiego (On the Genesis, Accounts, Valor, Knightly and Domestic Affairs of the Famed Peoples of Lithuania, Samogitia, and Ruthenia) adds notable information to the analyses of the structure and locations of exposition of Sigismund Augustus’s tapestry collection. Stryjkowski wrote this work in 1575–1578 as a way of thanking the Duke of Slutsk, Yuri Olelkovich, for his protection. Later on, the author rewrote the chronicle as a work of prose, and it was released in 1582 in Königsberg. The rewritten version was the first printed history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania – The Chronicle of Poland, Lithuania, Samogitia and all of Ruthenia. The earlier versed chronicle was never published. Stanisůaw Ptaszycki (1853–1933) found its manuscript in the Radziwiůů family’s library in Nesvizh in 1903 and mentioned it in the publication Pamićtnik Literacki. The manuscript then disappeared and was not rediscovered until 1966.76 The content of the versed and prose versions is not identical. The historian and poet writes of the European rulers’ 1429 conference in Lutsk in both chronicles. However, in the versed version, the palace halls, decorated with textiles and afftami (Polish hafty – needlework) are also described; only political events are described in the prose text. The text about the tapestries is in the subsection “O zacnym zjeędzie i sůawnym weselu w Ůucku i jako Witoůd przemyúlaů z Ksićstwa Litewskiego królestwo uczyniă, za powodem cesarskim roku Pańskiego 1429 (On the Venerable Congress and Glorious Wedding in Lutsk, and How Vytautas decided to Transform the Grand Duchy of Lithuania into a Kingdom, at the Ruler’s Behest, in 1429). In the text, alongside its description of the tapestries depicting David and Goliath, are mentioned The Story of the First Parents, The Story of Noah, and The Story of Moses. We also find new storylines, including those portraying the legend of the Lithuanians’ Roman origins and the brave deeds of the Lithuanian d 77 Mickűnaitë, “Motiejus Stryjkowskis apie Lucko suvaţiavimŕ,” 10. ukes. In the opinion of Radziszewska, Stryjkowski could have written this text after visiting Wawel Castle in Kraków and being inspired by the shimmering opulence of the tapestries there. It is hard to comment on this claim. Indeed, no information on the existence of tapestries featuring these other storylines (including the mythological plots) in the collection of Sigismund Augustus has survived. However, we are confounded by the fact that the other tapestries described in the text are well known, and their descriptions are quite accurate. Art researcher Giedrë Mickűnaitë, who analyzed the context of the text and images in the versed chronicle, noticed that Stryjkowski had good knowledge of, and often cited, ancient Roman myths and literature, which is why, according to the author, it is unlikely that he could have made such obvious slips.77 The poet mentions David and Goliath. The Goliath Series tapestries are mentioned in Sigismund Augustus’s will; however, no further information about them has been found.

When reviewing the versed chronicle’s descriptions, it is of note to recall the account book entry of January 14, 1546, already cited, about the acquisition of Sigismund Augustus’s “paintings,” where another five paintings are mentioned: The Emperor’s March Against Aurelius Barbarossa, The Sinking of the Ship in the March, Duke of [illegible] March near the City of Hahndorf [?], Duke Julius Cloven’s [?] March near the City of Hansburg, and The Emperor Drives the King of Italy from Naples. Perhaps they were actually woven, and Stryjkowski related them to Lithuania’s historical context. Sources confirm that, between 1572 and 1578, the poet visited Wawel; however, he could not have seen these tapestries there, because they were removed from the walls in 1559; and in 1572, all the tapestries, treasures, and other riches were removed from all of the ruler’s palaces and residences and transported to Tykocin. However, Stryjkowski lived in Lithuania from 1564 to 1574, and could have most definitely visited the Palace of the Grand Dukes in Vilnius.

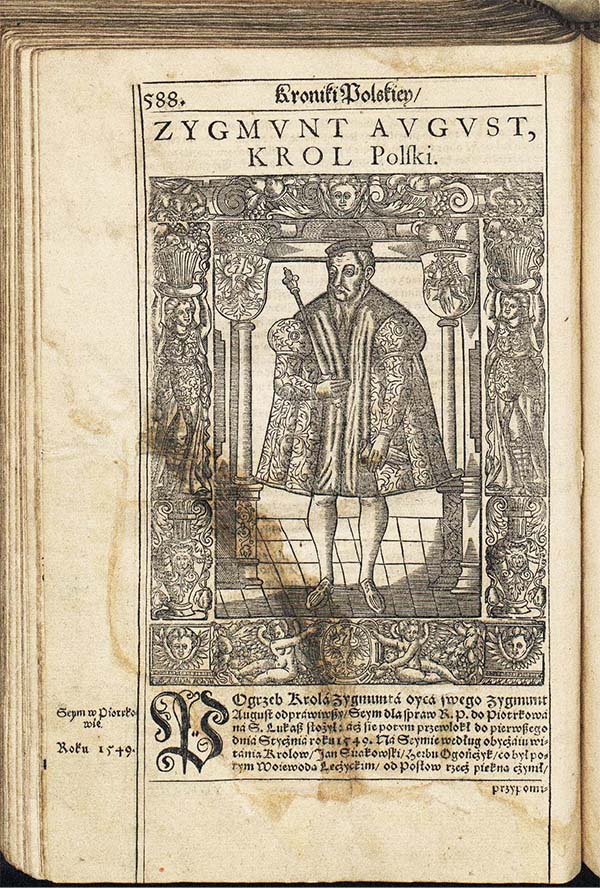

Other Literary Descriptions of the Tapestries

Nevertheless, Stryjkowski’s description did not receive much attention from researchers, and the series depicting the ancient history of Lithuania’s dukes and gods remained an expression of the poet’s imagination. It is strange, however, that a similar vision was seen by Joachim Bielski (1540–1599).78 Ewa Chojecka79 wrote about this in an article about the woodcut illustrations in Bielski’s Chronicle of Poland (1597), which portray Lithuania’s and Poland’s rulers and similar themed tapestries mentioned twenty years earlier in Bielski’s poetic panegyric Istulae convivium in nuptiis Stephani I regis (Kraków, 1576), written to commemorate the wedding and coronation of Anna Jagiellon and Stephan Báthory. After a colorful description of Stephen Báthory’s entry into Kraków, the text moves on to its central topic – the series of historically themed tapestries featuring images of Lithuania’s and Poland’s rulers. The work names forty-two rulers, beginning with the legendary figures and ending with Báthory. Also mentioned are two tapestries of a historical and legendary theme displayed in the dining hall at Wawel. The author mentions that the tapestries were woven with gold thread and had warm tones. The description begins with this sentence:

When such things were said about you by the gods, raising their full glasses and grappling over whom could drink more, the Queen ordered the British-made tapestries [opony] to be displayed, in which Sarmatian nymphs gaze with wonderment at Lech and his descendants...80

|

| Sigismund Augustus, in an illustration from Bielski’s 1597 Chronicle of Poland. Note the tapestry-like composition of the woodcut. See Sigismund Augustus’s Tapestries on page 37. |

In the course of discussing the series’ provenance, the author, basing her assumption on the fact that this set does not feature in the will of Sigismund Augustus, ascribes its commission to Anna Jagiellon. A possible date for the creation of the set, as noted by Chojecka, is the period between the death of Sigismund Augustus in 1572 and his widow’s wedding in 1576, or more precisely, at some point between 1575 and 1576, for an image of Stephan Báthory is also mentioned.81 Chojecka expressed many doubts about the supposed British origin of the textiles. As is known, at that time tapestry workshops in England were not producing high quality work, which is why the author concludes that this set might have been woven by Flemish weavers in the manufactories at Wawel. They may have fled Flanders to England during a period of political unrest and gone from there to the palace of the Commonwealth’s ruler.82 In the opinion of Chojecka, it is very likely that it was precisely these tapestries that were portrayed in the illustrations of Bielski’s Chronicle of Poland. The author bases this assumption on the fact that the figures depicted in the tapestries featured in the woodcuts and in the panegyric correspond with each other, apart from a few exceptions, and the composition of the woodcuts is reminiscent of tapestries, i.e., there is a central plane with figures and borders (see illustration on page 4). Chojecka believes that the set, lost without trace, could have been destroyed when fire broke out at Wawel in 1595.

Bernasikowa, who analyzed the information presented by Chojecka and her writings on the possibility of the set’s existence,83 draws our attention to the fact that the first knowledge we have of tapestry looms at Wawel dates only to 1602, when carpenters were said to have hewn timber to make “tailors’” looms.84 This is twenty-six years after the period Chojecka mentions as a possible date when the set could have been woven. The size of the Wawel workshops and the identities of its workers are unknown. It is thought that these looms were used to restore existing textiles, rather than for the manufacture of new ones. No information indicates that the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth served as a center for tapestry weaving during this period. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, rulers and magnates generally commissioned their textiles in Flanders, which is why it would be logical to assume that, if Anna Jagiellon had decided to commission this series, she would have followed in the footsteps of her brother and father and directed her commission to Flanders. On the other hand, it is unlikely that Anna, a princess constantly in conflict with the Polish council over her brother’s inheritance, could have allowed herself such an expensive consignment. A count of the images mentioned, even assuming one textile could have featured several figures, makes it evident that the set would have had to constitute several dozen textiles, which, according to Bielski, were woven with gold thread.85 Bernasikowa notes that, unlike Orzechowski, Bielski does not present any specific information about the textiles themselves: neither how many there were, nor where they hung.

It is therefore unlikely that the woodcut illustrations in Bielski’s Chronicle of Poland are accurate copies of the tapestries described in the panegyric. Even though the names of the figures portrayed do in essence correspond, Chojecka herself admits that, judging by the description (except for the name of the figure portrayed), it is completely unclear what a majority of the tapestries depict.

However, this does not mean we can discard the possibility that Bielski was a participant in the wedding and coronation celebrations, saw the historically and mythologically themed tapestries, and associated them with Lithuania’s and Poland’s history. Still, determining the themes of those tapestries is impossible, because Bielski’s description lacks detail, and its author has been maligned by later researchers for his unscientific understanding of material, his uncritical eye, and his indiscriminate presentation of history and legend.

Literary sources mention that analogical versed historical tapestry descriptions can be found in the panegyric of Georgius Sabinus, dedicated to the wedding of Sigismund Augustus and Elisabeth of Austria, as well as in U. Hette’s Panagyricus ad episcopum Albertum. We should also note that it was only the concept of the description that was similar, while specific figures and events in the tapestries differed.86

Nevertheless, despite their differing interpretations, the historical and legendary tapestries mentioned by four chroniclers and historians were most likely part of Sigismund Augustus’s collection.

Other Sources of the Collection and Sigismund Augustus’s Last Will

The collection under analysis was also supplemented by the dowries of Sigismund Augustus’s first wife, Elisabeth of Austria (1526-1545), and his third wife, Catherine of Austria (1533-1572). Elisabeth of Austria, who married and came to live in Kraków in 1543, brought with her two sets of figurative tapestries: The Story of Romulus and Remus (eleven pieces) and The Story of Nebuchadnezzar (twelve pieces). Following her death, both sets remained with Sigismund Augustus and were brought to Tykocin along with the other treasures.87 After Catherine of Austria married in 1553, she brought with her twenty-one tapestries, seven of which depicted the Allegories of the Virtues – Faith, Hope, Charity, Justice, Prudence, Temperance (or Restraint) and Fortitude (Fides, Spes, Caritas, Iustitia, Prudentia, Temperantia, Fortitudo); six depicted stories from the Old Testament; and eight depicted scenes with animals (viridia cum floribus et animalibus). Departing Kraków in 1566, the ruler took some of the textiles with her, including ten tapestries with the coats of arms of Lithuania and Poland, perhaps a gift from Sigismund Augustus.88 After the death of Catherine of Austria in Linz in 1572, the Allegories of the Virtues set ended up with the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II (1564–1576) and is now part of the Viennese state collections.

Sigismund Augustus’s collection also contained the tentapestry set The Story of Julius Caesar, which depicted Goliath, and other donated textiles. The surviving inventories from September 29, 1572 and September 9, 1573 help us understand more about the collection’s composition.

On May 6, 1571, Sigismund Augustus prepared his will, which was written up by his general secretary, the mayor of Vilnius, Augustyn Mieleski Rotundus (ca. 1520–1582).89 In the will it is written:

Thus, the textiles were bequeathed to Anna Jagiellon, Catherine Queen of Sweden, and Sophia the Duchess of Braunschweig- Lüneburg (1522–1575).91 If one sister passed away, her part had to be divided amongst the remaining sisters, and when the last had passed away, the items were to become the property of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, i.e., the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.92 An exception applied only to the liturgical dishes, which were to go to the Church of St. Anne-Barbara in Vilnius; a golden cross, which was to be donated to the family chapel in the Kraków cathedral; and Sigismund Augustus’s books, which were bequeathed to the Vilnius Jesuit Academy.93 This decision was without precedent, because at that time rulers usually considered their wealth private property that would remain in the family.

Sigismund Augustus spent his last days in Tykocin. In a document dated 1572, it was written that, after summoning the old captain Belinski, “he obliged me to keep my knightly word and made me promise, in the name of the Lord Almighty,” that he would not reveal the secret he was about to hear and that he would definitely carry out the order he was about to receive. The secret revealed to him was Sigismund Augustus’s plan:

...to bring from Vilnius, as from Knyszyn, all his treasures to Tykocin Castle, I was entrusted with serving as security, and he received my word that I would not give either that treasure or the key to it to anyone after the death of the King, only to Princess Anna. Having pledged to do so, I was instructed to bring everything that was kept in Vilnius to Tykocin.94

Why Tykocin? The answer to this question can most likely be found in a letter dated May 16, 1550, written by Sigismund Augustus while he was in Niepoůomice, to Mikoůaj “The Red” Radziwiůů, regarding removal of the title of Elder of Tykocin from Jan Radziwiůů (d. ca. 1550) and his rights to the castle, blaming poor upkeep. The ruler wrote:

Clearly, Sigismund Augustus considered Tykocin his safest residence, which, in the event of unrest, could have served as a refuge for Barbara Radziwiůů. It is thus completely unsurprising that when he sensed his own death was near, he decided to have all his amassed treasures brought to this location.

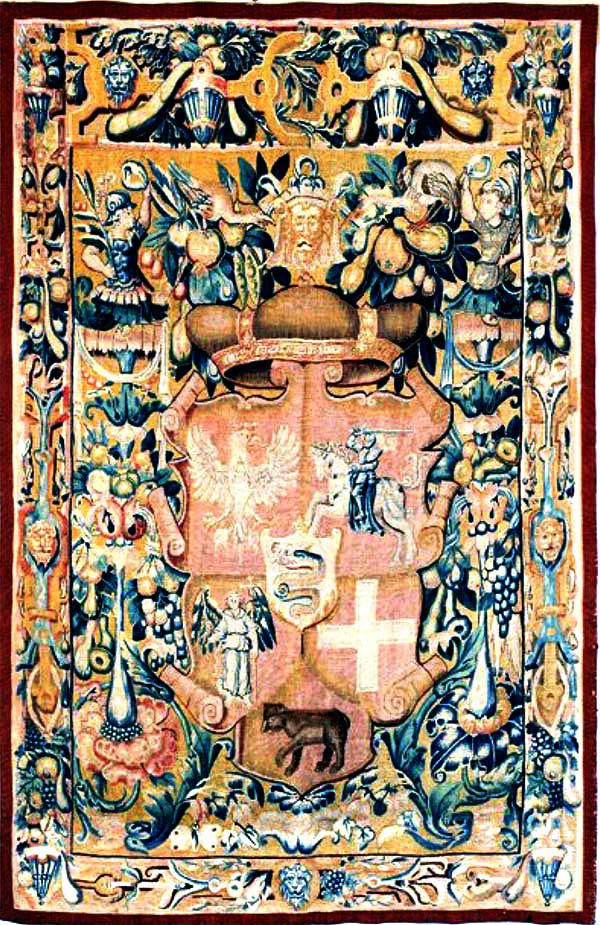

Only a meager portion of the collection has survived to this day, the largest part made up of the Great Flood tapestries. Most of the surviving tapestries are currently exhibited at Wawel Castle in Kraków; some decorate Warsaw’s royal castle; and one mid-sixteenth century armorial tapestry, with the combined Lithuanian and Polish coat of arms of the Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund Augustus, acquired at a Paris auction in 2009, is part of the collection of the Lithuanian rulers’ palace in Vilnius.

Summary

The available material allows the conclusion that tapestries played an important role during the era of the last Jagiellons in both the personal and public life of the rulers, decorating interiors during some of the most momentous occasions: coronations, weddings, funerals, state celebrations, and the reception of honored guests. The tapestries were a significant decorative and representative feature, not just of the Polish residences, as had been previously thought, but also of the residences of the Lithuanian rulers. Both in Kraków and in Vilnius, their use was similar, that is, they were hung in representational rooms during celebrations, receptions, and ceremonies, while at other times they adorned the rulers’ personal apartments and bedrooms.

The will of Sigismund Augustus, unprecedented in its historical context, even bestowed a political status upon the tapestry collection. Its protection and attempts at reclamation became a source of constant disagreement between later rulers and the Polish nobility. Some rulers, such as Stephen Báthory and John II Casimir Vasa, used the Great Flood collection as an instrument of blackmail to obtain certain personal privileges from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Analysis of the tapestry collection’s associations with the historical context of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the due comparison of material by various researchers, the facts and arguments that substantiate this material, and historical sources which reveal personal details from the life of Sigismund Augustus, as well as the latest archival sources, lends itself to the conclusion that the early biblical series tapestries – The Creation of the World, Noah’s Ark and The Great Flood – were commissioned in 1546, while the ruler lived in the residence of the Grand Duke of Lithuania in Vilnius. The years 1548–1550 are a probable date for their presentation.

No archival information has been found regarding the commissioning of the animal-themed tapestries or the armorial textiles. Nevertheless, the analysis of scientific research and the stylistics of the textiles would suggest that the tapestries with landscapes featuring animals were commissioned soon after the figurative sets. Which residence were they intended for? At the time Gćbarowicz and Mańkowski’s monograph on the subject was written, it was doubted they were meant for Wawel. In the authors’ opinion, unlike the representational figurative tapestries, the landscape textiles must have been used to decorate one of the rulers’ hunting residences, for example, Tykocin or Knyszyn. This is evidenced, they say, by the format of the textiles – they are suited to smaller spaces than the halls of Wawel.96 It is difficult to determine which of the residences these textiles were destined for. However, tapestries and other treasures from the ruler’s collection were transported from Wawel and other residences to Vilnius soon after the wedding of Sigismund Augustus and his third wife, Catherine of Austria, in 1553, as both newlyweds moved to Vilnius.

Even less is known about the commission date and purpose of the grotesque and armorial tapestries, yet the association of both the verdures and the armorial and grotesque textiles with Dermoyen is clearly only one of several not particularly well-founded hypotheses. As was already discussed, Dermoyen participated in the formation of Sigismund Augustus’s collection between 1559 and 1564 and, at the ruler’s request, intermediated in the acquisition of the black-and-white tapestries in Antwerp. The possibility that Dermoyen presented other sets earlier is less likely, because in the period between 1552 and 1559, his name often appears in the financial records of various Antwerp enterprises, where he performed a variety of services. Only in 1561 do we have the first information about his activities as a tapestry agent delivering an opulent gold, silver, and silk woven tapestry set to the King of Sweden, Erik XIV.

It is interesting to speculate on what purpose the textiles commissioned between 1559 and 1564 with the intermediation of Dermoyen were meant to serve. Based on the record by Zaleski, the tapestries that were at Wawel were covered and taken down in 1559. It is also known that this was when Sigismund Augustus ceased visiting Wawel.97 And archival sources mention the transportation of tapestries from Kraków to Vilnius and their hanging in the palace halls between 1559 and 1561. We also know that during this period the ruler spent 80 percent of his time in Vilnius, because it was his favorite residence. The possible association of these textiles with the Vilnius residence is also evidenced by the letters of Sigismund Augustus to Kostka, which indicate that the reimbursement of Dermoyen, already delayed for three years, should have been made from the treasury of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

These facts reveal a somewhat

different evolution of Sigismund

Augustus’s collection, suggesting significantly closer

ties with the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania in Vilnius

than has been hitherto believed. Unfortunately, they do not allow

for the identification of specific textiles or their location of

exposition.

* * *

Meanwhile, on the other side, there

hung a wall carpet

Depicting the Old and New Testaments.

How the Lord first created the world, the sea and the sky,

The birds, animals, and made man’s body from clay.

How Eve, made from a bone taken from his side, like

A devious snake, tempts him with an apple in Paradise.

After that, he sweats and toils to earn bread

And complains too late about his transgression.

Meanwhile, Noah was in his ark during the terrible flood,

And later, God with him reached an agreement, whose sign is the rainbow.

Here God speaks to Abraham, wanting his family

To multiply like the stars in the sky.

Here Joseph rules in Egypt with honor

And tests his brothers over the mortal sin they committed against him.

Here father Jacob is greeted, and his family too,

With great joy, while tears confound me.

Here God and Moses guide the Jews across the sea,

While the pillar in the sky shines, glowing bright.

The Pharaoh and his army drove across the Red Sea,

Where his pride and boastful heart perish.

Here in the desert, manna takes sustenance from the sky

And speaks proudly against God.

A steer was produced to free them,

And what happened to Moses and those tablets.

How Korah, Dathan, and Abiram perished

And how the fortified city of Jericho was taken by the Jews.

Thirty-one of its pagan kings fell at their hand,

While five were hung on an oak tree.

How the brave Yael stood with her hammer in hand

And struck a spike into Sisera’s temple.

After her, Gideon, Jephthah and the mighty Samson,

Who with bone in hand fought the Philistines

And also ripped apart a lion and carried

The city gates upon his shoulders.

How, betrayed by Delilah, he brought down

The temple on his enemies and bravely died with them.

How the body of the giant Goliath

David’s right hand sent to Hell.

How Judith killed Holofernes in the tent

And gloriously freed the Jews from besiegement.

I also saw there a beautiful painting

Of the Lord Christ’s works and miraculous transformation,

How God became Man, born of a Virgin,

Destroyed the Devil and Hell, and healed the injured world.

After that – how He judges the world, the dead rise from their graves

And account for their deeds, good and evil.

Pluto, waiting for the treasure, from the dungeon of Hell

Peers out – if you saw him, you would surely shake in fright.

And, when Judgement is made, the good are

Guided by angels to the eternal pleasures

Of the Elysian Fields, where they stay

And for their virtues and devotion receive rewards from God.

After that, I also saw how the others

Were led to Pluto by servants in a long line.

All bitter, covering their black foreheads with snakes,

Spitting burning flames from their jaws.

Here black Charon takes the evil across the River Styx,

While the damned suffer eternal torment.

Here are those who measure their beloved homeland in pounds,

And those greedy judges who took bribes.

How wonderful this wall carpet of Vytautas was

How exquisitely painted, that even its memory brings joy.

Many other things can also be seen,

So many, that it is impossible to count them all,

And those who wish to do so are better off counting the grains of sand

on the coast of Libya

Or the stars in the heavens. [...]

The rooms were prepared differently for each guest

And also decorated with excellent wall carpets,

That even Solomon did not have such luxurious rooms,

When Sheba came to him in all her splendor.

Especially there, where we sat, everything was of gold.

An embroidered carpet, beyond description.v

In it, famous deeds can be seen

Of the Romans, sailing to these rich lands.

How God took Palemon over the sea from Italy

How the Goths made with them a friendly treaty.

How Barkus, Speras, Kűnas build castles,

How Kernius and Ţivinbudas expand their domains.

How Mingaila, wearing shining armour, took Polotsk,

How Skirmantas and the Tatars bravely defeated the Duke of Lutsk.

And how Ringaudas took tribute from the defeated Russian princes,

After him, Mindaugas received the crown in Lithuania,

My, how bravely he pelted the Mozurians and Crusaders.

How Treniota was killed, and how Vaiđelga

Saw Germantas the brave with Đventaragis.

Giliginas, Trabus, Romanas, Nerimantas, Daumantas, after that

Alđis, Traidenis, and Giedrius – in the golden cuirass.

Vytenis – the valiant duke, and Gediminas – conversely,

Fighting the Crusaders, he often wears his armor.

He puts forth his sons, while Kćstutis and Algirdas

Battle with the Germans, the Poles, with Moscow’s skunks.

That was how this family of Lithuanian dukes was marshaled

And now can be seen by all so finely embroidered […]

Translated by Vaiva Naruđienë

* * *

The background and borders of this impressive tapestry are decorated with plant, architectural, and geometrical motifs, masks and lions’ heads, and in the center, the combined Polish and Lithuanian coat of arms of Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund Augustus (1544/1548–1572) topped with the great crown of the grand dukes of Lithuania.

The heart of the coat of arms depicts98 the arms of Sigismund Augustus’s mother, Bona Sforza, daughter of the Herzog of Milan – a serpent swallowing a child. Woven in the first field is the Eagle of the Kingdom of Poland, the coat of arms of Sigismund Augustus’s father, Sigismund the Old (1506–1548), with the initials of Sigismund Augustus on the eagle’s chest. The second field has the armorial symbol of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Mounted Knight (Vytis). The three coats of arms in the bottom fields are of the important lands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (The Angel represents Kiev; the Cross, Volhynia; and a Bear on all fours, Smolensk). Based on the interpretation of Dr. Edmundas Rimđa, this armorial composition could be read: The Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund Augustus is the son of the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund the Old and Bona Sforza, the ruler of Lithuania and its lands (Kiev, Smolensk and Volhynia).

This combined coat of arms of Sigismund Augustus was minted on the coins of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania during his reign and was also used on the state seal of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

|

| Tapestry with the combined coat of arms of Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund Augustus from the set Armorial Tapestries of Sigismund Augustus. Wool and silk; 240 x 158 cm. Acquired by the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania at an auction organized by Etienne de Baecque at the Drouot-Richelieu auction house in Paris on April 8, 2009. More details on page 80. |