Copyright © 2013 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Editor of this issue: Mikas Vaicekauskas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2013 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume

59, No.4 - Winter 2013

Editor of this issue: Mikas Vaicekauskas |

The Lithuanian Acta Sanctorum:Unknown Hagiography by Motiejus Valančius

MIKAS VAICEKAUSKAS

MIKAS VAICEKAUSKAS is a senior researcher at The Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore in Vilnius, Lithuania, edits two journals, and is the author of a monograph and numerous articles on Valančius. He is currently working on a documentary and critical edition of Kristijonas Donelaitiss Metai.

Abstract

The Samogitian bishop Motiejus Valančius (18011875) was a

pioneer in the field of hagiographic literature in the Lithuanian

language. His two published acta

sanctorum stand out for the

originality and individuality of their style. In the historiography

of Lithuanian literature, these works link early didactic

literature and later fiction. His corpus has recently been expanded

by newly-discovered manuscripts of hagiographic stories:

Žyvatai šventųjų II

(The Lives of the Saints II, 1864), Darbai

šventųjų (The Works of the Saints, 18741875), and a copy

of

the latter. The texts are interrelated and were affected by the

sociopolitical circumstances of the period. They considerably

expand the earliest Lithuanian corpus of acta sanctorum,

enrich

the creative biography of their author, and add new information

to the history of Lithuanian fiction.

Valančius,

his literary work and hagiography

The Samogitian Bishop, historian, writer, prosaist, publicist, and translator, Motiejus Valančius (18011875), was an especially sociable and dominating figure in the Lithuanian Catholic Church (bishop 18501875) and the cultural life of Lithuania in the middle of the nineteenth century.1 By that time, Lithuania, after the third partition of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth in 1795, had lost its independence and was in the domain of the Russian Empire. Subjected to a different political system, Lithuania was reorganized as a province of the empire, where Russian laws were in effect, enforced by the Russian bureaucracy. Attempts to completely Russify everyday life, the expansion of Orthodoxy, and an intense persecution of the Catholic Church were carried out; the education system was reorganized, the Vilnius Censorship Committee established, and strict censorship imposed.

In the nineteenth century, there were two national liberation uprisings against Russian authority, in 18301831 and 18631864, which had as their main objective the restoration of the Polish-Lithuanian Republic or the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Both uprisings failed. After the first, repressions ensued: Russification expanded, censorship intensified, monasteries closed, the rights of local citizenry were curtailed, nationalism subdued, and the Uniates (Eastern-rite Catholics) annexed to the Russian Orthodox Church. The most consequential repressive action was the closing of Vilnius University. Lithuania lost its sole academic institution, which had negative implications for Lithuanian culture and society.

After the 18631864 uprising, repressions increased: martial law, in effect till 1872, was enacted, Russification intensified, the lands of those involved in the insurgency were confiscated and redistributed to Russians, and roughly eighty Catholic churches were closed; those that remained open were, along with the seminaries, subjected to intense scrutiny. The center of the Samogitian Diocese the bishop and his administration was relocated to Kaunas for stronger surveillance. The Russification of Lithuanian education started with shutting down Lithuanian-language parochial schools and replacing them with Russian ones with Orthodox Russians appointed as teachers. Temperance societies were outlawed, printing in traditional Lithuanian (Latin) script was banned, and student textbooks were printed in Lithuanian, but in the Cyrillic alphabet, the so-called grazhdanka. Total Russification and the expansion of the Orthodox Church were underway.2

|

| Lithograph portrait of Motiejus Valančius

by Leonas Noelis, 1854. (LDM, G 2668) |

Bishop Valančiuss activities can be treated as an attack on the repressive measures taken by Russia. Before the uprising of 18631864, these included the temperance movement, organizing the education of the general population, and book publication. After the uprising, he encouraged priests to turn their attention to the people, sought to strengthen the publics trust in the Roman Catholic Church, supported the process of organizing secret schools, and supported the contrafactual publication of Lithuanian books3 and Lithuanian book smuggling. Valančiuss multifaceted activism generally defined the direction of the late nineteenth-century Lithuanian national awareness movement.

Valančiuss oeuvre comprised scholarly and educational works: scholarly and educational literature, practical religious literature, fiction, religious-political publications, homilies, and epistles. He wrote in a variety of genres: historiography, hagiography, didactic narratives, religious-political essays, personal notes and reminiscences, sermons, pastoral and personal letters, etc. Valančius devoted his literary labors to a wide audience, including peasants who had only recently learned to read and those still learning to read. A didactic element prevailed, including examples of positive lives (perfect, ideal, honest, pure, and God-fearing) and negative (sinful), as well as moral and practical teachings. These works were designed to act on their readers and change them.

The didactic and practical goals of Valančiuss creative work and his audience shaped the nature of his prose. He used a model of didactic literature closely connected with medieval and Catholic prose in the baroque style. Signs of baroque poetry and the influence of religious writings are especially obvious. Another obvious element is the educational nature of the texts, underscored by utilitarian directives. Another source of Valančiuss creativity was the oral tradition of Lithuanian folklore. In the history of Lithuanian literature, Valančiuss didactic prose, such as Vaikų knygelė (The Childrens Book, 1868), Paaugusių žmonių knygelė (The Adolescents Book, 1868), Palangos Juzė (Juzė of Palanga, 1869), and Pasakojimas Antano tretininko (The Tale of Antanas the Tertiary, written in 1872, first published in 1891), is rightly considered the predecessor or forerunner of Lithuanian fiction.4

When literary historians note that Valančius is considered one of the first authors of other genres in Lithuanian literature as well, they have in mind historiography, such as Žemaičių vyskupystė (The Samogitian Diocese, 1848); Pradžia ir išsiplėtimas katalikų tikėjimo (The Birth and Expansion of the Catholic Faith, 1862); translations of psalms, Pasalmės arba Giesmės Dovydo karaliaus ir pranašo (Psalms or Chants of David, King and Prophet, 1873); and political and social essays, for example, Apie sielvartus Bažnyčios šventos (The Sorrows of the Holy Church, 1868); Šnekesys kataliko su nekataliku (Conversation between a Catholic and a Non-Catholic, 1868); Vargai bažnyčios Katalikų Lietuvoje ir Žemaičiuose (The Troubles of the Catholic Church in Lithuania and Samogitia, 1869).

Valančiuss hagiographic works deserve a special place in his heritage. Along with his pioneering status in other genres, he is rightly considered the founder of hagiographic literature in the Lithuanian language, which began to be written and translated in the middle of the nineteenth century.

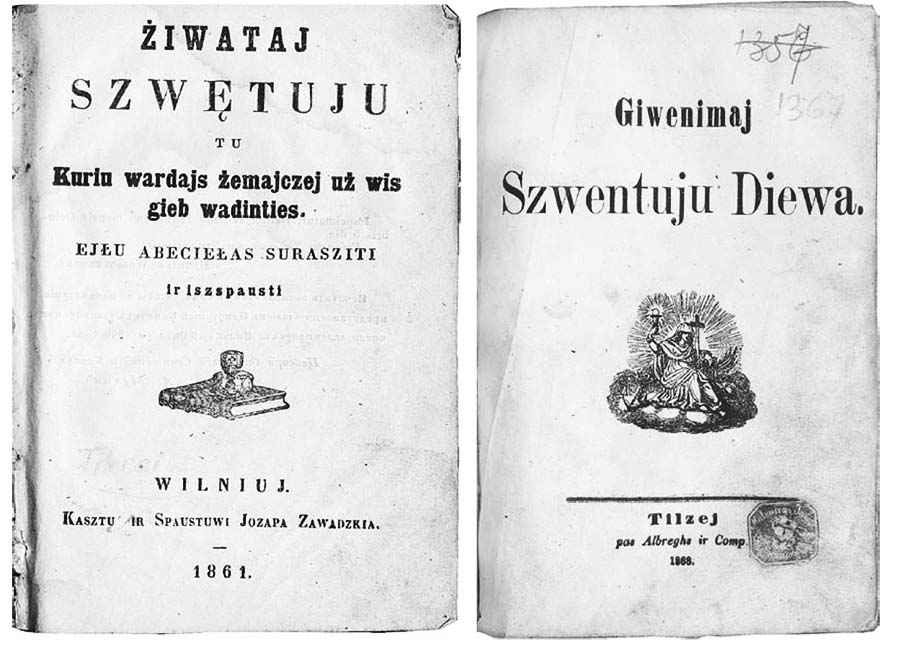

So far, it is known that Motiejus Valančius wrote and published two hagiographic works, Žyvatai šventųjų (The Lives of the Saints, 1858) and Gyvenimai šventųjų Dievo (The Lives of the Gods Saints, 1868), the first books of this kind in the Lithuanian language. Žyvatai šventųjų has been the archetype of Lithuanian hagiography for a long time. A total of 128 descriptions of the lives of the saints were presented in these books.5 The works titled Žyvatas Jėzaus Kristaus Viešpaties mūsų (The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ, 1853) and Gyvenimas Švenčiausios Marijos Panos (The Life of the Holy Virgin Mary, 1874) are also deemed hagiographies. These constitute the corpus of Valančiuss acta sanctorum, which is noted for its originality and unique style.6 Discussions of the birth of Lithuanian prose fiction, which occurred in the nineteenth century, single out Valančiuss hagiographical works as a link between early didactic writings and Lithuanian literary fiction.

|

|

Title

pages of Valančiuss Žyvatai šventųjų (1861; first edition 1858) and

Gyvenimai šventųjų Dievo (1868) (LLTIB, 2241; LLTIB, 1367) |

Valančiuss statement in the preface of Žyvatai šventųjų that he had presented the life of those saints whose names the Samogitians [Lithuanian Lowlanders] like to call themselves has drawn attention from practically all the researchers of Valančiuss works.

The author wrote the following in the preface to the book:

Only God, the Lord himself, knows how many Catholics became saints. The Church counts the martyrs themselves and many other devoted servants of the Lord in thousands of thousands. Therefore, if anyone wanted to list just the names of all the saints, he would write big books. Knowing this, I left a description of all the servants of the Lord to those who are mightier than me, and I recorded the lives of only those saints whose names the people of our land use to name themselves. Actually, it will be nice for everyone to know who his guardian or patron was, what good he has done, and for what actions he became a saint. Therefore, I wish my beloved Catholics to read this book and, having become acquainted with the good deeds that the saints have done, to start following their example and become saints themselves. May God, the Lord, grant this to everyone.7

This selection of the saints in Valančiuss first book is related to the purposes of his entire cultural, enlightenment, and social activity. In the interest of forwarding reading and literacy, he provided his Lithuanian audience with a wide repertoire of reading material, ranging from practical religious books to historical works and fiction. Books on the lives of the saints, related to the local environment as much as possible, were a part of this repertoire. Intended for his familiar community, these books, containing information about concrete heavenly guardians, also appealed to the intellectual interests of the community.

The newly discovered hagiography by Valančius

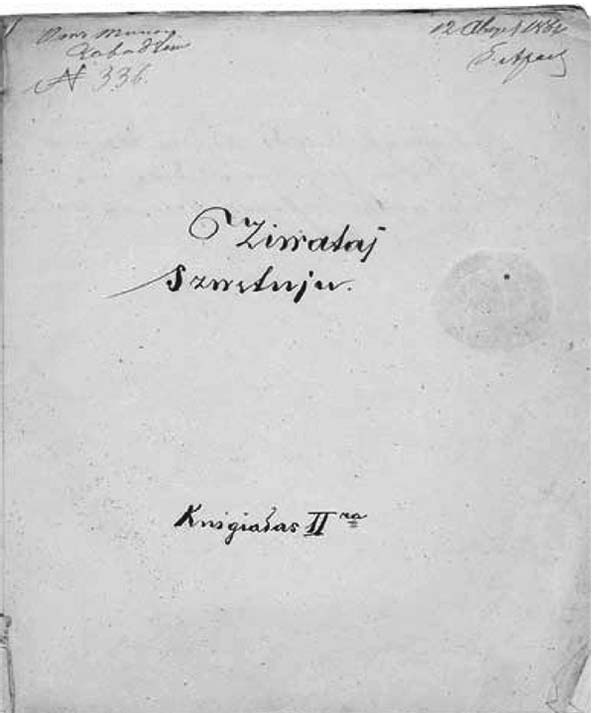

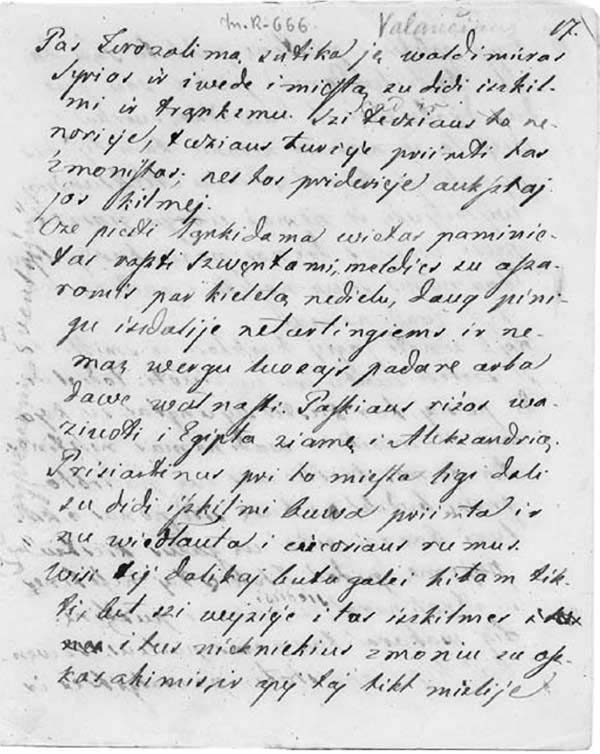

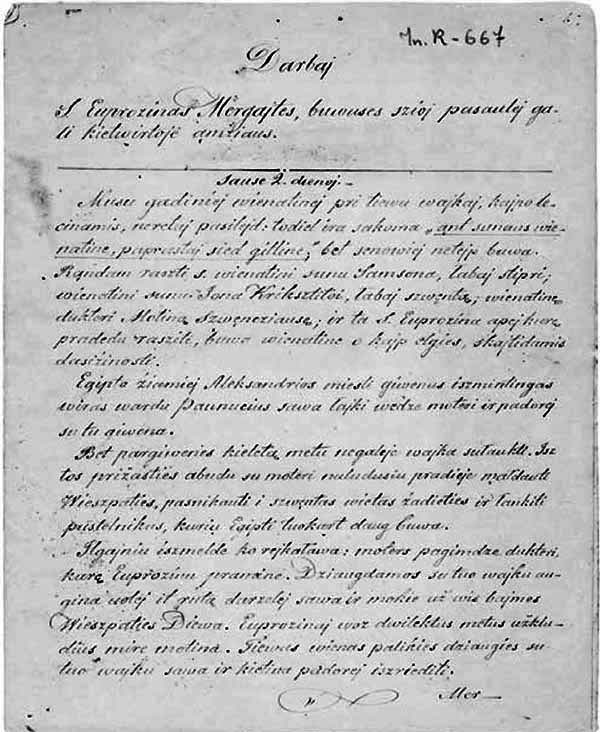

Valančiuss acta sanctorum corpus has recently been supplemented with some previously unknown manuscripts. They are Žyvatai šventųjų II (The Lives of the Saints II), written in 1864, and Darbai šventųjų (The Works of the Saints), written approximately between 1874 and 1875, and a clean copy of the latter. The title of this work Darbai šventųjų was given by me, based on the first eleven lives of the saints.8 The manuscript of Žyvatai šventųjų II, containing the lives of 28 saints, is a copy that was not made by Valančius himself, but prepared for publication by someone else. The manuscript of Darbai šventųjų is written in Valančiuss hand; the copy of Darbai šventųjų is a clean copy made by an unidentified scribe, containing 53 descriptions. These works have been neither recorded nor studied thus far.

|

|

The

title page of the copy of Valančiuss Žyvatai šventųjų II (1864) (LLTIB

RS, f. 1, b. 674, p. [I])

|

|

|

| The

beginning of Valančiuss manuscript Darbai šventųjų (18741875) (LLTIB RS, f. 1, b. 666, p. 17) |

The

beginning of the copy of Valančiuss Darbai šventųjų LLTIB RS, f. 1, b. 667, p. 1) |

The manuscript of Darbai šventųjų is defective: it is unbound, has no title page, its beginning and some of its pages are missing,9 and it contains no indications of its history. The work is incomplete; the description of Gregory Nazianzens life abruptly ends on page 567. Judging by the paper, handwriting, the history of book printing,10 and a comparison to his later manuscripts Broma atidaryta į viečnastį (The Gate Open to Eternity), Pasakojimas Antano tretininko, and his other written works, it can be dated to 1874 or 1875. The copy of Darbai šventųjų is also defective: some of its pages and the title page are missing,11 and it likewise contains nothing that a researcher could use to definitively establish its history. The missing pages of the autograph most often do not coincide with those of the copy, so we practically have the whole text of the work.

The copy attests that the book was being prepared for printing, as is the opinion in the case of Broma atidaryta į viečnastį.12 However, the scribes identity is only speculative (the handwriting points to Laurynas Ivinskis), and the date of the copy might suggest a different interpretation altogether. Upon deeper analysis of the manuscripts history, one might come to a different reason for the copy: the copies of Darbai šventųjų as well as Broma atidaryta į viečnastį were written by the same hand and neither was intended for publication. The copies were made posthumously, most likely after an examination of Valančiuss last will and testament. Possibly, they were copies of unpublished works the scribes thought might be published at some point.

More can be said about the manuscript of Žyvatai šventųjų II. It is dated by the author himself, I wrote this in Varniai, May 31, 1864.13 This is probably the date of his imprimatur and not the date of the completion of the copy or of the original. However, in light of Valančiuss extraordinary ability and pace of work, one can postulate that the book was both finished and then copied by a still-unidentified scribe in 1864. As evidenced by the text of Žyvatai šventųjų II and other remarks in the manuscript, Valančius had someone prepare it for printing, i.e., an unknown scribe had made a clean copy to be submitted to the publisher. The manuscript was also proofread and minimally edited by Valančius himself, which is evident from the editorial remarks and corrections made in the manuscript text by Valančius, who used a lighter ink than the scribes. He edited the punctuation, diacritical marks, and quotation marks throughout the text. Valančius himself gave this work his spiritual approval and put a seal on it.

The manuscript ended up in the hands of the publisher Adomas Zavadzkis. This is evinced by the inscription made by the censor on the title page: От типогр[афа] Завадского ([Received] from the publisher Zavadzkis).14 The manuscript was at that point in the hands of a member of the Vilnius Censorship Committee, Viktoras Julijonas Aramavičius (18161892), who was the unofficial censor from November 23, 1857 to February 23, 1865.15 The title page bears the date 12 August 1864 Viktoras Aramavičius,16 written by him when he received the manuscript from Zavadzkis. The date on the fore-title page, 21 November 1864,17 is most likely the date when the manuscript was reviewed or returned to Valančius. Apparently, the manuscript did not receive publication permission, because it contains neither the censors approval nor any other marks characteristic of censored manuscripts, such as the censors signature, the special method of sewing the pages together, a seal, marks on the pages, or an indication of the publisher and the place of printing.18 It is doubtful that this was connected to the Lithuanian press ban, which had not yet taken hold everywhere by that date.19

Censorship, however, was especially strict in 1864 and 1865. When Mikhail Muravyov became Governor-General of Vilnius, Pavel Kukolnik, head of the Vilnius Censorship Committee, had to deliver all of the Lithuanian books obtained by his committee to him. A verbal decision by the Governor-General was final and would act as a basis for a censors decision.20 According to Darius Staliūnas, in 1864 the Censorship Committee received thirty-seven applications for the publication of Lithuanian books, but from January 1865 until the fall of that year, no such books reached the Committee. Therefore, it is credible that M. Muravyov simply would not allow such books to go through.21 It is difficult to say whether Valančius was aware of this situation. Perhaps that was the reason he never edited Žyvatai šventųjų II and never delivered it again to the Vilnius Censorship Committee.

However, following the regulations of the censorship of the Russian Empire and its policy of promoting Orthodoxy, the censor Viktoras Julijonas Aramavičius made other notable changes to the manuscript of Žyvatai šventųjų II.

One of the most important considerations in censoring publications was respect for religion and the Church, the necessity for holiness, and the inviolability of essential truths and dogmas of the Christian faith, particularly those of the Orthodox Church. The Russian government had announced equality and tolerance toward all Christian religions, but the Orthodox Church was untouchable, and polemics against it or indeed any criticism was forbidden.22 Russian authority had little tolerance for critiques of the Church:

The censors were very stringent and would strike any antiorthodox expressions from text that pertained to the Orthodox faith, the Church, the Orthodox community in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, or individual members of the clergy. All this was equated with anti-Russian sentiment toward the Russian nation and the state.23

All Lithuanian or Polish books published in Lithuania were also censored for items related to the Uniates (Eastern Rite Catholics). When, on June 23, 1839, the Uniate Church was annexed to the Orthodox Church by imperial order, censorship policies regarding Uniates were formulated. The order first forbade the announcement of the order itself. A negative view was cast upon historical and literary texts that focused on the Union of Brest, the Grand Duchys compulsory conversion of those of Orthodox faith into Uniates, the conflicts between Orthodox Christians and Roman Catholics, and religious unrest in Ukraine. Mention of the Uniate Bishop St. Josaphat of Polotsk (Juozapatas Kuncevičius, 15801623, beatified in 1643, canonized in 1867), who fought against the Orthodox believers in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and converted them into Uniates, was undesirable and prohibited.24

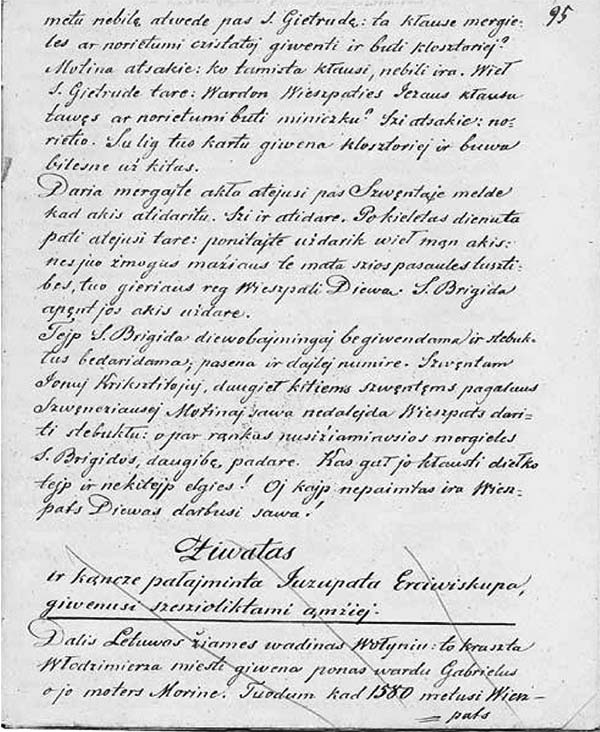

|

|

The

life of St. Josaphat crossed out by censor Viktoras

Julijonas Aramavičius in the manuscript of

Žyvatai šventųjų II (LLTIB RS, f. 1, b. 674, p. 95) |

Therefore, following the censorship instructions regarding anti-Orthodox positions or language offensive to the Orthodox faith, and in keeping with Russias negative attitudes towards the Uniates, the censor Aramavičius, in pencil, crossed out the life of St. Josaphat written on pages 95106; he also crossed out the record S. Iuzapata Erciwiskupa in the index section of the manuscript, on page 159. It is possible that crossing out this part of the text was the reason the manuscript was returned to the author. Valančius did not correct the text, and did not describe the life of St. Josaphat in his later collections on the lives of the saints. Soon the ban on using the Lithuanian script began, and official publication of Lithuanian books in this script stopped. The question of why Valančius did not publish Žyvatai šventųjų II in the contrafactual way he did with his other books, or why he wrote other hagiographic works such as Gyvenimai šventųjų Dievo, published contrafactually in 1868, and Darbai šventųjų, remains open.

Around 1873, Valančius, in his notebooks and memoirs in Polish, Wiadomość o czynnościach pasterskich biskupa Macieja Wołonczewskiego (News Concerning the Pastoral Works of Bishop Motiejus Valančius),25 made a list of his written and published works under the title Wiadomość literacka (Literary News).26 Here, he made a note about his written saints lives: 8. Žyvatai šventųjų. Wrote this in 1858. Printed at Mr. Zawadzki. Not sure about the number of copies and 15. In 1866 wrote second part of the lives of the saints titled Gyvenimai šventųjų. Printed in 1868.27 Valančius did not mention Žyvatai šventųjų II. From the second note, we could assume this to be Žyvatai šventųjų II, but Valančius noted the Lithuanian title of the book, Gyvenimai šventųjų Dievo, and 1868 as the year of publication, which is also recorded in bibliographies of Lithuanian books.28 So the question of why Valančius did not mention Žyvatai šventųjų II and Darbai šventųjų in this list, even though other manuscripts are mentioned Pasakojimas Antano tretininko, Garbinimas švenčiausios širdies Dievo mūsų Jėzaus Kristaus (The Worship of The Sacred Heart of Our God Jesus Christ), Gyvenimas Švenčiausios Marijos Panos, and the contrafactual copies of Vaikų knygelė, Paaugusių žmonių knygelė, Palangos Juzė, etc. remains open, at least until new evidence or archival records related to this issue are discovered.

After Valančiuss death in 1875, Alfonsa Beresnevičiūtė, the daughter of Valančiuss sister Petronėlė Beresnevičienė (1805 1867), and Stanislovas Gruzdys (18691939), the grandson of Beresnevičienė and son of Petronėlė Beresnevičiūtė-Gruzdienė, took on the safekeeping of his remaining manuscripts.

The Lithuanian Scholarly Society, founded in 1907,29 had numerous social and cultural activists who worked tirelessly to compile its library and archives. Private letters and classified advertisements in the periodical press urged people to come forth with manuscripts.

Priest Juozas Tumas (18691933) was one of the most ardent activists involved in preserving Lithuanias cultural heritage. While publishing Tėvynės sargas (The Guardian of the Homeland, 18971902) and Žinyčia (The Repository of Knowledge, 19001902), he collected manuscripts and had access to others, as well as ample information about manuscripts pertaining to famous past social and cultural personalities, especially those connected to Lithuanian literature. This may have been how Valančiuss remaining manuscripts came to light.

When the Lithuanian Scholarly Society began compiling archives, Tumas joined in wholeheartedly, providing information about various manuscripts or ensuring their transfer or donation to the Society. Apparently, this was how Tumas came to be involved in the transfer of Valančiuss manuscripts to the Societys safekeeping. On October 5, 1908, Tumas donated to the Lithuanian Scholarly Society Valančiuss manuscripts Mokslas Rymo katalikų (Roman Catholic Teaching), Pasakojimas Antano tretininko, Garbinimas švenčiausios širdies Dievo mūsų Jėzaus Kristaus, Patarlės žemaičių (Samogitian Proverbs), Žyvatai šventųjų II, Darbai šventųjų and its copy, Mykolas Olševskis Broma atidaryta į viečnastį and its copy, several smaller texts, and correspondence with Vladislovas Beresnevičius, the son of Valančiuss sister Petronėlė Beresnevičienė.30 While transferring the manuscripts, he compiled a list of them.31 Later, the manuscripts were described and incorporated into the Lithuanian Scholarly Society manuscript catalog.32

At the Lithuanian Scholarly Society, Žyvatai šventųjų II and Darbai šventųjų, as historiography and archival documents attest, attracted little attention. On September 29, 1940, the inventory of the Lithuanian Scholarly Society was transferred to the Lituanistic Institute,33 which ceased operations on January 16, 19 1941, upon the establishment of the LSSR Academy of Sciences, and the holdings of the institute were subsequently placed in the academys custody. The library and the archive were relocated to the library of the Lithuanian Literary Institute,34 now the Lithuanian Literature and Folklore Institute.35 The manuscripts were catalogued in 1946 by Ona Miciūtė, incorporated into Pirmoji rankraščių įrašymo knyga (The First Manuscript Records Book), and assigned inventory numbers.36 The manuscripts are stored there to this day.

The manuscripts of Žyvatai šventųjų II and Darbai šventųjų have not been codified or explored anywhere in Lithuanian literary historiography related to Valančiuss descriptions of saints lives,37 with the exception of the recent first mention.38 Tumas donated the manuscripts to the Lithuanian Scholarly Society, but since he made a roster of the donated works without examining them, he mislabeled Žyvatai šventųjų II as the manuscript of the already printed Gyvenimai šventųjų Dievo.39 Žyvatai šventųjų and its copy were also mislabeled, as Šventųjų gyvenimai, i.e., the manuscript and copy of the printed Gyvenimai šventųjų Dievo. The donation was mentioned in the press at the time, but the manuscripts were not scrutinized and their titles not made public.40

Some literary and writing characteristics of Valančiuss hagiographies

Literary historians have established, based on collections of hagiographic narratives of the time written in other languages, that Valančius wrote rather than translated his published hagiographic collections.41 Valančius did not indicate the exact sources, with one exception in Žyvatai šventųjų, near the story of St. Georges life, he noted (Joanes Bolandus. Vttae Sanctor. Tom. XV).42 Possible sources that can be mentioned include Petras Skargas Żywoty świętych (first published in 1579, with numerous reprints in the nineteenth century), the Latin publication of Société des Bollandistes, and some separate Polish publications of the time. But the sources that Valančius drew on in writing his acta sanctorum corpus have yet to be definitively identified.

Valančiuss narratives have a noticeable connection with Skargas lives of the saints: the course of events and the timeline, the structure of the text, identical situations, and the factography (names, places, and dates). There are even similar statements in his work. However, there are also obvious differences: Valančiuss narratives are much more concise, eliminating some details of the events. Skargas lengthy disquisitions on the meaning of sanctity and martyrdom are also omitted, replaced by brief moral exhortations. Valančiuss narratives particularly distinguish themselves in their literary expression, tonality, and the language and style of the narration.43

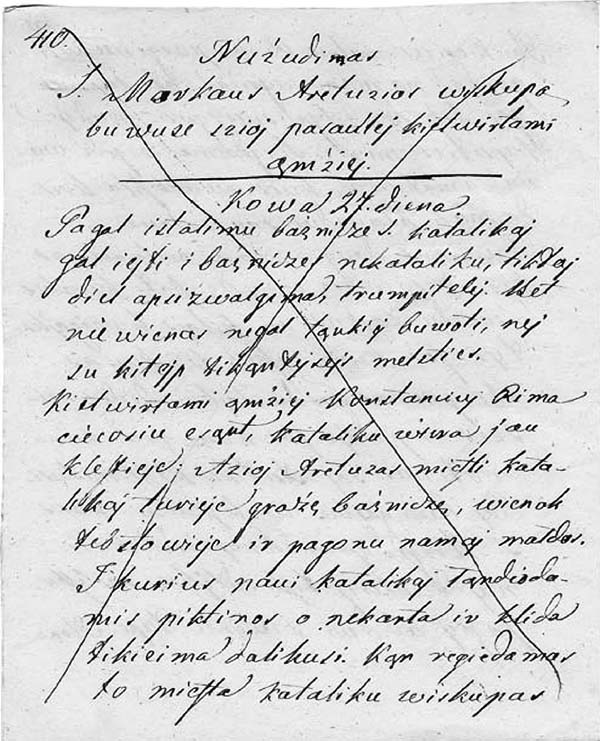

In light of the character of Valančiuss entire body of work, its scope, the number of books written and published, and also having the available autographs in mind, some comments can be made on his manner and method of writing. It should be noted that the manuscript of Darbai šventųjų is practically a clean copy, with very few corrections or amendments. It is likely that Valančius wrote the lives of the saints with a source or two in front of him after reading the life story of some saint, for example one by Skarga or another non-Lithuanian text, he immediately wrote down his own narrative. The story about the life of St. Mark from Arethusa contained in the autograph of Darbai šventųjų could confirm this supposition. Having written this story once, on pages 255259, Valančius described the life of this saint a second time, one hundred and fifty pages later (on pp. 410413). However, the second version is a completely different story. Only the structure of the texts and the main events from the life of the saint are the same; the vocabulary, expression, and dynamics of the narration differ.

|

| The beginning of the life of St.

Mark from Arethusa in Darbai šventųjų (LLTIB RS, f. 1, b. 667, p. 410) |

The following two narratives are taken from his separate treatments of the life of St. Mark from Arethusa.

The first reads:

Afterwards,

taking off all his clothes, they tied him up and rolled

him into a ball. They smeared him with lard and honey, and

placed him in a winnowing basket up high in the sun, so that

wasps and flies and other bugs would suck out all his blood.

From high up, the Bishop mocked them, saying, Why did you

do this? Im sitting higher than you are. He was glad to suffer

the torture in the name of Christs faith. [...]

The pagans marveled, seeing such fortitude in the old man, but

did not cease the torture until his soul was cast out and went

straight to the Lord, where it reigns forever.

Amen.44

The second reads:

Moreover,

they tore all his clothes off, smeared him with honey,

sat him in a winnowing basket, and raised him up high with a

rope in the sun, so that flies and gadflies would suck out his

blood. He survived in the winnowing basket for three days,

when finally, without food or drink, he stopped bleeding and

gave up his soul to God; praise is to him forever and ever.

Amen.45

When Valančius noticed that he had related the life of St. Mark from Arethusa twice, he crossed out the second version. From this evidence, one can conclude that it was not a mistake made in copying a text, but rather an example of a completely spontaneous manner of writing. The spontaneity of Valančiuss writing, executed with minimal reliance on his own earlier texts or other authors works, is also shown by the fact that the lives of the saints in his hagiographical works had already been described in earlier books and manuscripts. Žyvatai šventųjų II includes a description of the life of St. Apollonia; Gyvenimai šventųjų Dievo includes St. Agnes; Darbai šventųjų St. James the Lesser and Leo the Great; all of these saints were described in Žyvatai šventųjų. In addition, Darbai šventųjų includes the lives of St. Bridget, St. Euphrosyne, St. James the Lesser, St. Mary of Egypt, and St. Peter Balsam, who had already appeared in Žyvatai šventųjų II. However, all these stories, just as in the example of the story of St. Mark of Arethusa, are markedly different from their earlier versions.

In continuing the medieval and baroque tradition of hagiographic narrative, Valančius made it relevant46 and gave it distinct local (even everyday) features that related it to the life and environment of his period, depicting the people of antiquity and the Middle Ages as if they were Samogitian peasants of his time. In this manner, he sought to achieve authenticity and believability, so that the reader could understand the story better and feel that it was closer to him. Vanda Zaborskaitė attests that Valančiuss world and environment of saints has no separation from the readers environment. The feeling of closeness comes not only from the belief that all Christians, the living ones and the ones from the past, are members of the same Church: with his unique skill, as mentioned, Valančius is able to connect the Saints time and place with the readers home, his way of thinking, and his experience of life.47

Valančiuss hagiographic stories characteristically feature vivid imagery, chronologically delineated events, and twodimensional characters. The authors positions are presented openly; the heroes are idealized and the villains denounced. Usually, the story begins in one of two ways: with the place, the time of the action, and the name of the character, or else with a didactic thesis intended to establish contact with the audience,48 followed by its illustration the life of a saint and the most significant episodes of martyrdom and sanctity. The story ends with a moral conclusion, repeating the thesis given at the beginning of the story or reformulating it. For example, the beginning of the life of St. Bridget is as follows:

Oftentimes, folk take interest in others lineage. The ones born of the great are highly regarded, and the ones born of the common are regarded very little. But God, the Lord, doth this not. Often he extols the smallest through his grace, as he has done with St. Brigitte, whose life I have hereby described.49

Valančiuss writing employed a single style. He wrote everything in an informal register; he used the same words when describing both spiritual and mundane events. The rather scanty use of stylistic devices was in line with the didactic purpose of his works his epithets, similes, figurative verbs, comparisons, antitheses, direct speech, dialogues, exclamations, questions, and even onomatopoeic interjections are most often of an evaluative nature. Valančius is especially famous for his use of onomatopoeic interjections. For example, the story Palangos Juzė, which is consistently stylized with onomatopoeic interjections, is the only one of its kind in Lithuanian literature. He also used this stylistic device in his hagiographic stories, the late ones in particular.

Language is another feature that defines Valančiuss style. He wrote in the language of his audience. In his narratives, he used a living and expressive vernacular with a dialectal vocabulary, borrowings, idioms, synonymy, enumerations, comparisons, and proverbs and adages. All of this is executed with the help of literary devices, often adopted from religious works of the baroque period. It is worth noting that Valančiuss Patarlės žemaičių (1867) attests to his interest in folklore. Synonymy, enumerations, and comparisons are seen in the episode where devils frighten St. Anthony:

The devils, upon seeing that the saint had returned, turned into all kinds of different animals, surrounded the hut of the hermit, [and] started tearing it down and intimidating him in every way. Foxes barked, wolves howled, bears murmured, hogs grunted, pigs squealed, leopards mewed, lions roared, dogs howled. All of them with their eyes wide open, their ears cocked up, moved their mouths, wagged their tails, shook their crests, showed their nails, lifted their muzzles, opened their jaws like a flax-brake and clattered their teeth and tusks like tongs in a smithy.50

A detailed, thorough, baroque-like description of tortures (much more so than Skargas) is also characteristic of Valančiuss writing. The lives of the saints had to evoke a readers sense of holiness, miracle, pity, and fear. At the same time, he sought to surprise or frighten the reader. Here is a longer quote from the life of St. Mark illustrating both the detailed nature of the narrative and its expressiveness, as well as the use of similes, onomatopoeic interjections, etc:

However, some of Valančiuss contemporaries did not give the lives of the saints written in this original style a particularly good assessment. Following the traditions of the Enlightenment, seeking purely religious didactic enlightenment, the Lithuanian religious writer Laurynas Serafinas Kušeliauskas (18201889) some time later himself wrote and issued the multivolume Visų metų gyvenimai šventųjų (The Lives of the Saints for the Whole Year).52 He criticized Valančius for his style and language in the introduction to his book, writing:

This assessment may have been adequate at the end of the

nineteenth century, during the period of the Russian occupation,

14 Valančius, Ziwataj Szwęntuju II, [III].

15 Biržiška, Aleksandrynas III, 25455; Lietuvos TSR bibliografija 2:1,

136;

Navickienė, Aramavičius.

16 Valančius, Ziwataj Szwęntuju II, [III]; identified by Гринченко, et

al., История, 69.

17 Valančius, Ziwataj Szwęntuju II, [I].

18 Medišauskienė, Rusijos cenzūra, 37, 39; Navickienė, Besikeičianti

knyga, 51, 88.

Russification, the Lithuanian press ban, religious oppression,

and the persecution of the Catholic Church. However, it

was due to Valančiuss original style and his peculiar language

that his hagiographic work was reassessed from a creative perspective

in the twentieth century.

As a pragmatic man who was active in public life, Valančius

had a profound effect on the development of Lithuanian culture

and its society that has been inadequately appreciated. His

literary creations laid the groundwork for Lithuanian prose.

Valančiuss newly discovered hagiographic works Žyvatai

šventųjų II and Darbai

šventųjų substantially supplement the

early Lithuanian acta

sanctorum corpus and enrich the history

of Lithuanian literature, particularly the period of nascent Lithuanian

fiction.

*

* *

List of the saints in Motiejus Valančiuss

Žyvatai šventųjų

(The Lives of the Saints, 1858)

St. Agatha, St. Agnes, St. Anastasia,

St. Anastasia Widow,

St. Andrew the Apostle, St. Anthony of Padua, St. Apollonia,

St. Augustine, St. Barbara, St. Bartholomew, St. Benedict, St.

Bernard, St. Casimir of Poland, St. Catherine of Alexandria, St.

Cecilia, St. Christina, St. Cyprian of Carthage, St. Clement, St.

Dominic, St. Dorothy, St. Elisabeth of Hungary, St. Felix of Nola,

St. Florian, St. Francis of Assisi, St. George, St. Gertrude of

Nivelles,

St. Gregory the Great, St. Ignatius Loyola, St. James the

Lesser the Apostle, St. Jerome, St. John Nepomucene, St. John

the Apostle, St. Joseph, St. Juliana of Nicomedia, St. Lawrence

martyr, St. Leo the Great, St. Louis King of France, St. Luke the

Apostle, St. Marina, St. Mary Magdelene and Martha, St. Mark

28

the Apostle, St. Martin of Tours, St. Matthew the Apostle, St.

Matthias the Apostle, St. Paul the Apostle, St. Peter, St. Petronilla,

St. Philip the Apostle, St. Salomea, St. Scholastica, St. Simon

the Apostle and Jude Thaddaeus the Apostle, St. Sophia

and three daughters (Faith, Hope and Charity), St. Stanislaus,

St. Stephen, St. Teresa of Avila, St. Thecla, St. Thomas the Apostle,

St. Ursula and friends, St. Victoria, St. Vincent de Paul.

List

of the saints in Motiejus Valančiuss

Gyvenimai šventųjų Dievo

(The Lives of Gods Saints, 1868)

St. Abraham Kidunaja, St. Adalbert of Prague, St. Agnes, St. Anastasius, St. Andrew Bobola, St. Anselm of Canterbury, St. Antonina and Alexander of Constantinople, St. Aquilina, St. Basil the Great, St. Blaise and his friends, St. Catherine of Siena, St. Cyriacus, Smaragdus, Largus etc., St. Clement of Ancyra, St. Cuthbert, St. Edward the Confessor, St. Elphege, St. Ephrem, St. Erasmus (St. Elmo), St. Fausta, Evilasius and Maximinus, St. Faustinus and Jovita, St. Felix, St. Fursey, St. Gordius, St. Hilary of Poitiers, St. Ignatius of Antioch, St. Isaac, St. Isaac of Spoleto, St. James the Hermit, St. John Calabytes, St. John Chrysostom, St. John of Matha, St. Julian and Companions, St. Justin Martyr, St. Juventius and Maximus, St. Lucian of Antioch, St. Ludger, St. Lupicinus and Romanus, St. Lutgardis, St. Macarius, St. Margaret of Cortona, St. Margaret of Scotland, St. Maris, Martha, Audifax and Abachum, St. Mark and Marcellian, Martyrs of England, St. Medard and Gildard, St. Melania, Bl. Michael Giedroyc, St. Monica, St. Onesimus, St. Onuphrius, St. Paul the Hermit, St. Paula, St. Polycarp of Smyrna, St. Polyeuctus, St. Primus and Felician, St. Rupert, St. Sabbas the Goth, St. Sebastian, Marcus and Marcellian, St. Simeon Barsabae and Companions, St. Simeon the Stylite, Blessed Stanislaus, St. Theodora and Didymus, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Tiburtius, St. Timothy, St. Valentine, St. Vincent Saragossa, Sts. Vitalis and Valeria, St. Wulfram.

List of the saints in Motiejus Valančiuss

Žyvatai šventųjų II

(The Lives of the Saints II, 1864)

Adam the Patriarch and Eve, St. Alexander I, St. Aloysius Gonzaga, St. Alphonsus Maria de Liguori, St. Andronicus, St. Anne, St. Apollonia, St. Bridget, St. Constantia, St. Euphrosyne, St. Hedwig, St. Hyacinth, St. John the Merciful, St. Josaphat of Polotsk, St. Kinga, St. Leonard, St. Lucy of Syracuse, St. Mary of Egypt, St. Martina, St. Paul the Simple, St. Pelagia, St. Peter Balsam, St. Pius I, St. Roch, St. Romuald, Seven Holy Brothers, St. Veronica Giuliani, St. Vincent Kadlubek.

List

of the saints in Motiejus Valančiuss

Darbai šventųjų

(The Works of the Saints, 18741875)

Abraham the Patriarch, St. Alexander, Sts. Andronicus and Athanasia, St. Anthony, St. Antoninus of Florence, St. Apollinaris, St. Athanasius of Alexandria, St. Austrebertha, St. Basil and Glaphyra, St. Bridget, St. Catherine of Sweden, St. Cedd, St. Cyril, St. Cletus, St. Cunigunde, St. Equitius, St. Hermengild, St. Euphrasia, St. Euphrosyne, St. Francis of Paola, St. Gregory of Nazianzus, St. Guthlac, St. Hugh, Invention of the Holy Cross, Isaac the Patriarch and Rebecca, Jacob the Patriarch, St. James the Lesser, St. John the Merciful, St. Jonah and Barachisius, St. Ladislas of Gielniów, St. Leo, St. Macarius of Alexandria, St. Macarius of Egypt, St. Malchus, St. Margaret of Hungary, St. Mary of Egypt, St. Mark from Arethusa, St. Martinian, St. Nicetus, Noah the Patriarch, St. Peter Balsam, St. Peter of Verona, St. Peter, Sts. Philoromus, Phileas and others, St. Procopius, St. Richard, St. Sigismund of Burgundy, St. Tarbula and Pherbutha, St. Theodore, St. Theophilus, St. Vincent of Valencia, St. Vitalis, St. William of Maleval (St. William the Great).