Copyright © 2014 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Editor of this issue: Rimas Uzgiris

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL

OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2014 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume

60, No.1 - Spring 2014

Editor of this issue: Rimas Uzgiris |

Painting, Context, Self

MONIKA FURMANAVIČIūTĖ

MONIKA FURMANAVIČIūTĖ holds a B.A. and an M.A. in art from the Vilnius Academy of Art. She is in her fourth year of their new PhD program that combines theory and practice. Her work has been shown throughout Lithuania and Europe, and her paintings were selected for Art Vilnius 2012 and the 2013 Vilnius Painting Triennial.

In the continuous process of establishing and reflecting on one's situation in the social environment, an especially sensitive person can become a member of society who cannot and does not want to work mechanically. This is another way of describing the fate of the creative artist.

I have always been interested in the cultural environment in which I find myself, wondering why I am here, now, and what my purpose might be. In this way, I have probably always been looking for my true image. It always seemed like others have their "face," but that I was shattered and gathered up from thousands of contradictory parts. I began to suspect that many-sidedness is a characteristic or even an essential trait of a woman's nature. My study of the creative work of both genders helped strengthen this suspicion, and it was confirmed by my reading of the philosopher Luce Irigaray in her work on characteristics of women's self-conceptions. She argues that a woman's identity can't be merged into one single symbol - as opposed to men, whose gender can be expressed monolithi-cally by analogy to the phallus.1 Furthermore, in their study of women's autobiographies, researchers Anu Koivunen and Marianne Liljestrom have found polyphony, fragmentation, and a diaristic style to be features of the female gender. They speculate that women's unwillingness to write in the "ideal" mode of the genre of autobiography - the presentation of a coherent and continuous "I" - is a characteristic of women's subjectivity in patriarchal culture.2 I believe that such features can be found in the work of artists. One can see in the plastic structure of their images the motif of fragmentation or collage. For instance, Georgia O'Keefe paints flowers from such a close perspective that they become, on the one hand, abstract compositions and, on the other hand, allude to the female genitals. Furthermore, Frida Kahlo paints herself in an ever-changing environment that gives different meanings to each self-portrait, making herself at one time, for instance, a victim and at another an aggressor.3 According to Teresa de Lauretis, a woman's subjectivity is a web of momentary differences and revisions, or a never-ending, continuously refilled, renewing project, which is accurately exemplified by the image of fragmentation.4 The constant selection and coordination that gives new uses to old materials gives meaning to the heterogenous "I," in which not only is the heritage of patriarchy rethought as a woman constructs herself out of myriad elements, but the very genealogy of women is reconstructed and created anew.

While studying at the Vilnius Art Academy, I encountered pressure from the (largely male) academic environment to formulate a coherent "I" for myself - to not wander about in different forms of expression, but to rest in a single place. My colleagues seemed to have their own "I," but I found it much harder to reflect myself in that way. Their work, however, made it easier for me to see my difference. But why was I expressing myself heterogeneously? I began to reflect on the causes of, and influences on, our artistic development.

Even a few decades ago, knowledge of other cultures (especially Western) had been limited by the political situation during the occupation of Lithuania by the Soviet Union. The Iron Curtain resulted in strict censorship of artistic expression, limiting developmental pathways. Nevertheless, the influence of Western art movements such as Expressionism, Abstract Expressionism, and CoBrA began to trickle through. Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch, and Chaim Soutine were especially important in the first formations of new Lithuanian painting styles. In 1973, the group "4" was formed as the first collection of Expressionist painters in Lithuania. In the late 1980s, coincident with the birth of the Sąjūdis political movement, this artistic group grew into "24." Its members were made up of fellow students and later friends and artists with similar views: Kostas Dereškevičius, Arvydas Šaltenis, Algimantas Kuras, Algimantas Švėgžda, Ričardas Vaitiekūnas, Vytautas Šerys, Leopoldas Surgailis. They had a similar worldview and thinking about art. Whether working in greater abstraction or closer to realism, they all took their cues from Expressionism and a desire to oppose state structures, speaking the truth through art. They wanted to show the real nature of life at that time, without decoration. Those times saw the development, within the artistic context, of a movement towards the dramatic expression of everyday reality that put that harsh reality to shame while also discovering within it a quotidian beauty.

The emphasis on emotion that marked these Lithuanian Expressionists was counterbalanced by another group of painters formed in 1990, the neo-Expressionist Angis (Viper), who moved away from reality to a more self-reflective approach, analyzing the subconscious and the nature of art itself. Their nucleus was made up of people who are still active in the art world: Jonas Gasiūnas, Henrikas Čerapas, Ričardas Nemeikšis, and Antanas Obsarskas, among others. Their inspiration came largely from the European avant-garde group "CoBrA" (standing for Copenhagen, Brussels, Amsterdam -the cities in which its painters were based). They were united by a desire to experiment with painting materials and forms, also paying heed to the primitivism that was a trademark of the CoBrA movement.

These were important moments of change in the history of Lithuanian painting that influenced its future development, shaking up the cultural stagnation of the late Soviet period and stimulating new expression. Their influence was strong and manysided. Some of the painters from earlier generations who continued to teach at the academy, namely Jonas Gasiūnas, Kostas Dereškevičius, and Arvydas Šaltenis, had a significant influence on my development during my early studies. Under their tutelage, I tried out a wideranging palette and many styles, often working from nature. The essential feature that connects this generation of painters with my own is changing modes of figuration.

Artists are always conditioned by their technical means and their cultural environment. From a cultural perspective, painters in Western Europe had returned to the human figure, especially Willem de Kooning, Francis Bacon, and Georg Baselitz. The older groups of Lithuanian painters - 24 and Angis - created their figurative paintings from nature or from sketches and deformed them from that basis, or they created deformed imaginary figures, turning them into signs or symbols. Today, from a technical perspective, painting is being conditioned by photographs, producing a style called New Realism. The omnipotent power of the camera changed coloristic painting to one of tones. Attention has been given especially to changes of light (e.g., high-contrast flashbulb effects, low-contrast imitation of faded photographs) and to repainted images of people from deforming perspectives. Often, the fantastic elements in today's painting are nevertheless based on photographs, not drawn directly from nature nor simply pulled from the depths of dreams.

Thus, photography and painting are no longer held to be competing mediums. One could argue that, with the advent of photography, painting moved away from Realism to Expressionism and abstraction, while now there is a return to the photographic image as the base from which painterly imagination springs. The possibilities for connection and cooperation between the two mediums has come from the West, from such painters as Gerhard Richter, Marlene Dumas, Francis Bacon, and Lucian Tuymans. All of these artists use photography in the creation of their work, often in the form of images shaped by digital technology.

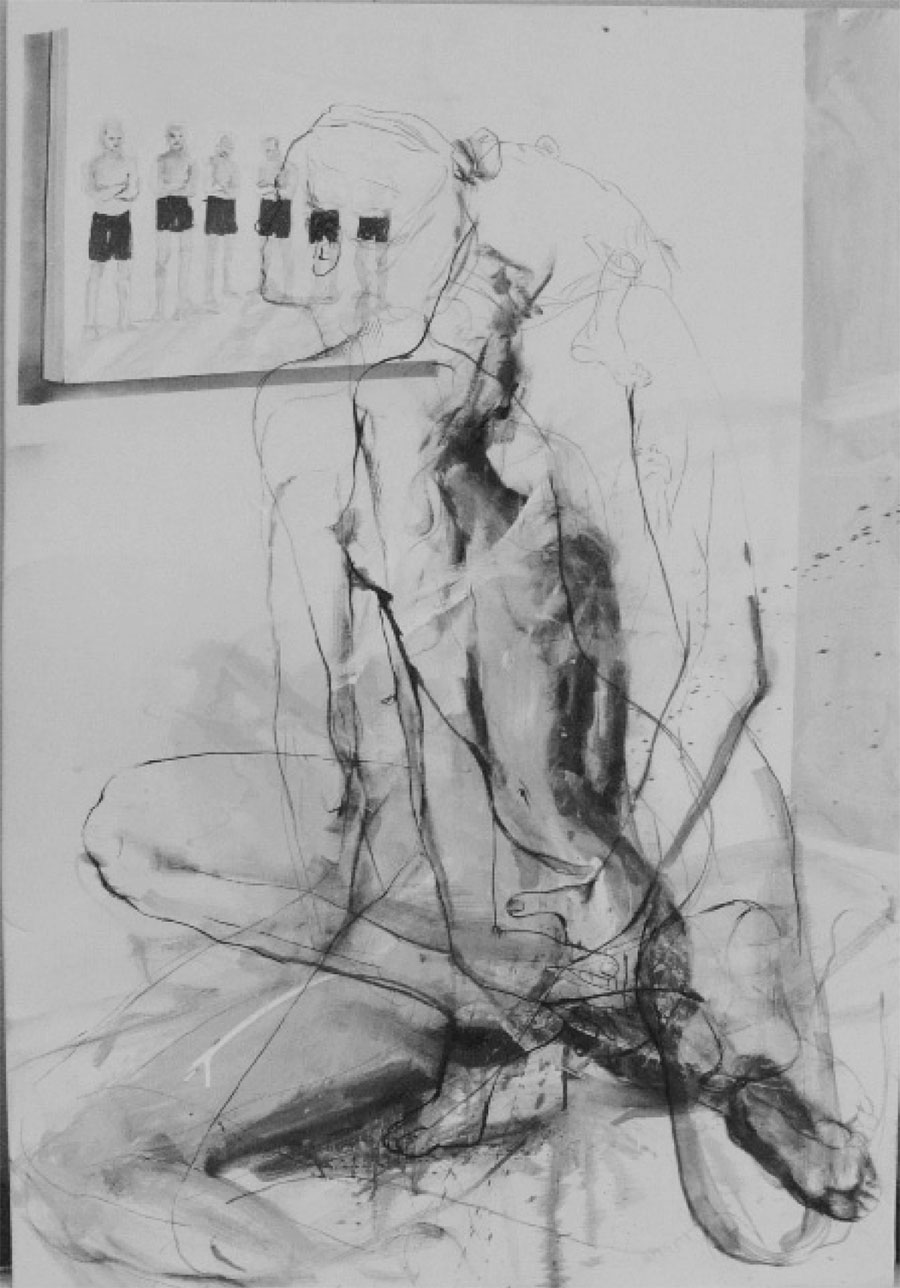

Later in my studies, I came to consider photography as a possible influence on my art when I chose the analysis of self as my primary theme. This signally changed my method of creating a painting. The woman's body began to find itself on the plane of my pictures in the form of a drawing done on the basis of a photograph. But not only was my painting changing under the influence of photographs, but that of my colleagues as well, such as Eglė Karpavičiūtė, Jolanta Kizikaitė, Konstantinas Gaitandži, and Jūratė Kluonė. In ways that I will explain later, an artist's expression becomes even more subjective when based on a photograph. Furthermore, the subject matter of the painting is often created according to the principle of collage, with changes in the dimensions of time and space (e.g., Gaitandži has painted Arnold Schwarzenegger in a Soviet uniform). Lately, painters using photographs have been exploring the themes of time and identity, projecting artifacts of the past into the present (e.g., Karpavičiūtė has painted Duchamp's urinal in a contemporary context). The work of the new generation is conditioned by globalization and emigration, the culture of state memory, individual self-understanding, and the waning of a clear sense of identity.

The fact that these young artists live in a new political environment, in a relatively young or reborn state, may influence their selection of the themes of time and identity in their work. The new generation does not think of itself as former citizens of the Soviet Union (something that naturally left its mark on the older generation), but they also lack a clear picture of themselves as citizens of the newly independent Lithuania. This quest for a new identity may be why they show a tendency to use their work to question old photographs (e.g., Jūratė Kluonė painting images of old family photos in minimalist surroundings). Differences between the original image (the photograph) and its reiteration (the painting) become the new face of painting - the new realism. Every reiteration of the photograph involves a change, so that the subject depicted is also changed, while also remaining more or less identifiable with the subject depicted in the original. Thus, the technique mirrors the nature of the changes in identity that the artist and the society as a whole are going through. And in this way, the new generation generates its own identity that is, nevertheless, connected meaningfully with the past.

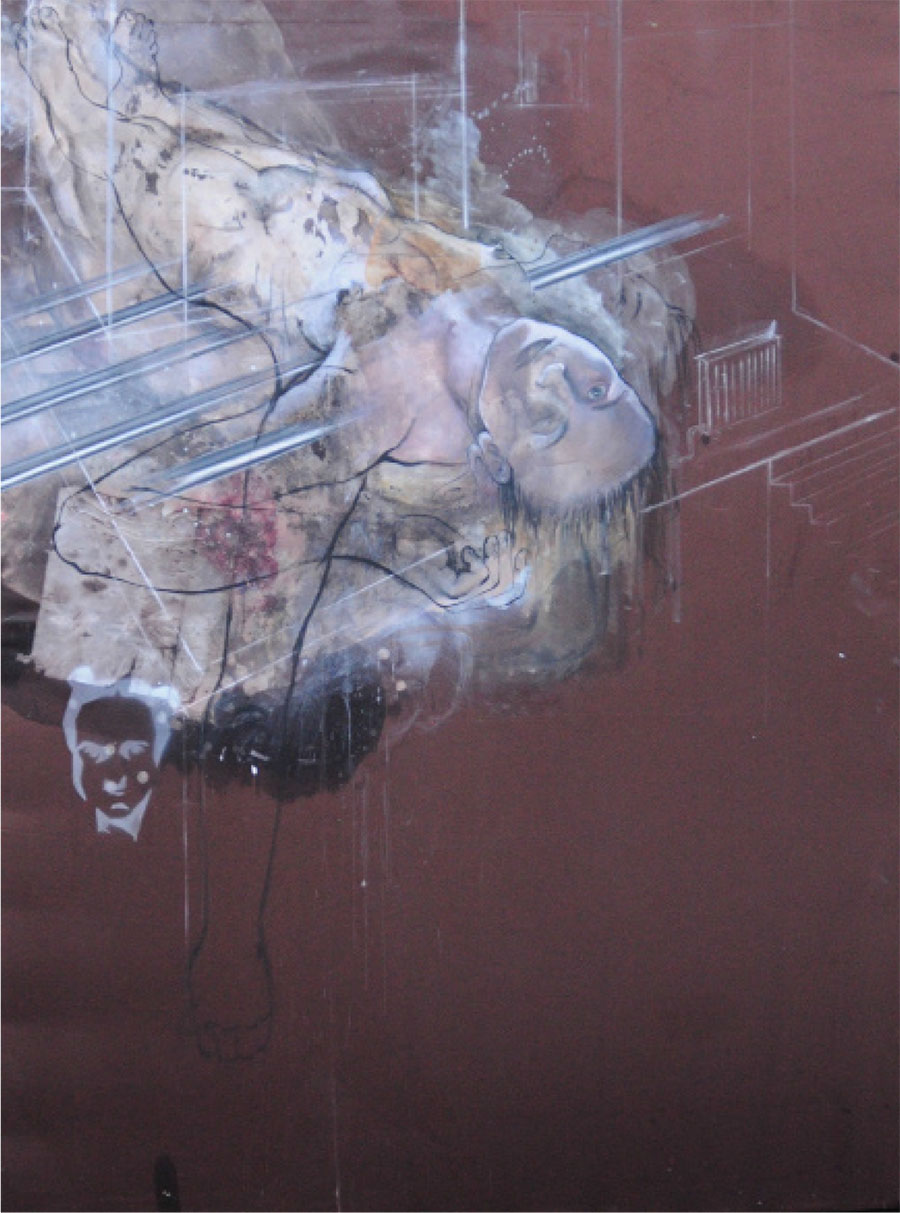

In my own work, I use photographs and computer programs to provide a flat image of reality over which my conscious and unconscious mind can play. With the help of these pre-existent images, the canvas becomes my screen onto which I project autobiographical details, facts drawn from life, together with the dreams and fictions of my imagination. My experience with video art has given me the necessary tools to transfer onto the canvas an understanding of the moving, cinematographic image. One can descry different "episodes," disparate elements which the spectator gathers together and ties into a subjectively constructed story.

Today's painter could be compared to Alice in Alice in Wonderland. She falls down the rabbit hole and is cut off from the "real" world, entering a world of fantasy or dream that draws upon images of her previous reality. Rational logic is abandoned, and a space is opened up for the play of unconscious impulses. Likewise, the contemporary painter has closed herself up in the studio, where images of reality, e.g., photographs, enter into associative play with the painter's subconscious. This unique interplay of subjectivity and objectivity gives rise to new discoveries and understandings of the self and one's identity.

The search for self-understanding has become the main theme that ties together my creative work. I analyze, in particular, women's identity through various aspects: woman/sacrifice, woman/mother, woman/pop culture, woman/religion, woman/sexuality. In doing so, I rely on my own experience - my emotions and thoughts transferred onto the plane of images in conversation with each other. Through self-analysis, I look for new possibilities of expressing who I am in my various roles as woman, artist, mother, daughter, lover, friend. Although there is a general interrogation of what it means to be a modern woman, because it is based on my own personal search, I use pictures of myself. This allows me to look at myself from the side, or from outside. In the interactions of photographs and paintings, I see myself from a third-person perspective, my personality and body transferred to the picture like an Other. It is as if I can then say, "that is not me, but only my image." In such a way, looking at myself from the outside, I gain the freedom to change, "rehabilitate," or even "heal" myself.

Another way of expressing the effect of photography on my art is to see the photograph as a first step away from me, followed by another step away in the process of putting the image on canvas. Thus, I am two steps removed from myself. The image literally becomes a third person - at a third remove from me. (In this way of conceptualizing it, we might recall Plato's discussion in the Republic of the artistic image being three steps away from the true reality of the Forms.) My image is thereby freed from the body, from personality, and from thoughts about myself. I gain the ability to change the image and how I think about my identity. (This freedom is not a possibility that Plato seems to have considered when he criticized the arts on the basis of their distance from reality.)

I think the situation is similar in the work of other young painters working from photographs in which historical figures, personalities, and objects are fixated. By manipulating these images as they transfer them to the canvas, they gain power over them. The initial pictures become "disarmed," so to speak, losing their status as a given and finished object, becoming open to manipulation and change as suited to the artist's ideas. In this way, the artist is able to re-think what has been given - an important strategy of postmodern art.

Thus, in my work, images from everyday life (teapots, light fixtures, and various shiny, metallic objects) are turned into signs that complement and comment on the image of the woman's body, which itself becomes a sign with its personality, individuality, and previous identity removed. My image becomes every woman's image, and so no specific woman, open to new meanings and understandings. In this way, the spectator is drawn into the process of identity creation. The picture of the depersonalized body becomes like a blank slate onto which the spectator can project thoughts and feelings, even imagining herself the owner of that body. Thus, men and women can have very different reactions to my work. On the one hand, men can often be carried away into a world of erotic fantasy - albeit limited and even opposed by elements of the grotesque. On the other hand, women will often consider the way in which their identity is shaped by the desires and expectations of those around them. My painting becomes interactive, engaging in a dialogue about what it means to be a woman in today's world.

Silk, a symbol of womanhood, has been the primary material on which I paint since 2008. The colors of various silks raise certain emotional impulses and relieve me from the burden of painting on the empty space of white canvas. This colored fabric becomes the first note of my work, the dominant key according to which I begin to improvise and project images one on top of the other. It can act as an unseen layer or a space for different times or events to overlap and enter into dialogue. It is on this surface that, using photographs as a base for my image creation, I most intensely began to explore the nature of my identity and the nature of modern woman in general. In these pictures of the last five years, I become victim and conqueror, food and feaster, desire and desired, adult and child, living and dead, and whatever else can be seen on the screen of the image captured, collected, and dreamed.

WORKS CITED

de Lauretis, Teresa. Technologies of Gender. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

Irigaray, Luce. This Sex Which Is Not One. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987.

Koivunen, Anu and Marianne Liljestrom. Sprendžiamieji žodžiai: 10 žingsnių feminizmo link. Aida Krilavičienė (trans.), Vilnius: Tyto alba, 1998.

Miscommunication, 120 cm x 90 cm, 2012.

Mixed media on silk.

Point B, 140 cm x 120 cm, 2013. Mixed media on silk.

Dessert, 150 cm x 175 cm, 2012. Mixed media on silk.

Menu, 180 cm x 160 cm, 2010. Mixed media on silk.

From to, 150 cm x 180 cm, 2012. Mixed media on silk.

Red Shoes, 165 cm x 130 cm, 2009. Mixed media on silk.

Miracle on the Beach, 130 cm x 130 cm, 2012.

Mixed media on

silk.

Positive, 150 cm x 170 cm, 2010. Mixed media on silk.

Teapot, 120 cm x 120 cm, 2010. Mixed media on silk.