Copyright © 2014 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Editor of this issue: Almantas Samalavičius

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2014 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume

60, No.2 - Summer 2014

Editor of this issue: Almantas Samalavičius |

Of Tradition and Imitation: Controversy in Contemporary Lithuanian Wooden Architecture

ARNOLDAS GABRĖNAS

ARNOLDAS GABRĖNAS is an architect and associate professor at Vilniuss Gediminas Technical University. Among many other aspects of architecture that interest him, he is currently concentrating on wood architectures practice and theory.

Abstract

This article examines how imitation appears in contemporary

wooden architecture and what its signs are, as well as discussing

positively evaluated methods of applying traditional forms

in new wooden construction. The artistic and functional qualities

of wood architecture built and designed in Lithuania are

analyzed in the context of Lithuanian and foreign architectural

trends and realities.

The tradition of using wood in architecture,

linked to ancient times by the historical heritage of wooden

architecture (whether that heritage survives physically or is lost but

preserved in the written record), has formed certain stereotypes and

associations in society as well as among professional architects. Wood

architecture and its expressions are frequently invoked when seeking to

convey traits characteristic of Lithuanian architecture. When striving

for architectural integration in a sensitive context, such as in older

town centers or villages built of wood, the use of wood is often the

primary factor in harmonizing new construction with its surroundings;

but form is extremely important as well. In such designs, the architect

must find a relationship between traditional form and contemporary

architecture's functional and aesthetic trends. On the one hand, the

historicity of wood architecture and an effective application and

interpretation of Lithuanian architecture's ethnic characteristics may

assist in creating a distinctive contemporary wood architecture. On the

other hand, the object may be evaluated as an unsuccessful imitation.

In this article, we examine when imitation appears in contemporary

architecture and what its signs are, and discuss the methods used in

those applications where traditional forms in new wood construction

have been positively evaluated. In the decades since an independent

Lithuanian government was established, questions about the artistic

expression of wood architecture have become particularly pressing as

wood gains in popularity and is increasingly used by planners and

builders.

A number of researchers have reacted negatively to the direct repetition of traditional architectural forms in new construction. Richard Dethlefsen wrote, as early as 1911:

Art that merely copies is dead, and only that which is still alive can be saved. [...] However, we want something else: that our craftsmen, particularly the young, learn the language of inherited forms, learn it in such a way that, in the future, creating independently, they could rely on historic examples and that it would become customary to them, as it had been earlier. Only then will it be possible to talk seriously about the survival of historic art traditions and their perpetuation.1

The author notes it is impossible to re-create the past in the present, but the continuation of tradition in new architecture is imperative.

In a Lithuanian context, detailed considerations of what actual form this could take appeared after the organization of the 1969 Lithuanian Summerhouse Architectural Competition in Toronto. This competition, which aimed to encourage the study of Lithuanian architecture and its application in today's world, requested that as many attributes of Lithuanian architecture as possible be imparted to the summerhouse's exterior architecture and interior plan. The six-plus designs submitted generated quite a bit of interest. Algimantas Banelis and Jurgis Gimbutas, commenting on the submitted work, agreed that in architecture, as in the other arts, national peculiarities are possible, but a simple application of the primitive decorative elements of barns and cottages in a contemporary building, particularly one functioning as a summerhouse, was neither meaningful nor logical.2 Apparently, at that moment, the participants in the competition, the organizers, and the critics were clearly convinced that harmony between the forms of traditional wood construction and contemporary modern architecture was a meaningful practical and theoretical architectural problem. Observing that traditional Lithuanian architectural characteristics in the submitted projects appeared somewhat like caricatures, the panel discussed whether it would be useful to look at the nature of ethnic construction in Finnish or Japanese examples, taking into account each country's climate, landscape, contemporary materials and techniques, and to some degree its historical heritage.3 At the time, other architectural scholars thought the same. Jonas Minkevičius highlighted Finnish architecture, asserting that the mechanical, banal imitation of traditional architectural folk motifs was not characteristic of its work, and that their schools of architecture, like the people themselves, in their innate qualities show reserve, a sense of moderation, an organic connection to nature, and the use of local materials.4 Gimbutas declared that, if designed by Lithuanian architects, entirely new architecture would already be Lithuanian of its own accord, campaigning in this way for "new individual creations" without "historical-traditional" markers.5

In the half-century since these discussions, the history of world architecture has been supplemented with new examples that offer a new approach to the problem of harmonizing traditional and contemporary forms in Lithuanian wood architecture.

Among the outstanding examples in which a communion between traditional form and contemporary architectural trends has been expertly expressed, pavilions for world fairs are memorable. These objects represent a nation in the eyes of the world, so a great deal of attention is given to the architectural expression of ideas and semantics in their design. Countries with wood-architecture traditions have built interesting pavilions at various fairs. At the 1992 World's Fair, Tadao Ando designed a wooden building as an interpretation of a traditional Japanese shrine. There are a number of allusions to historic Japanese architecture in the structure. The curved form of the wooden walls evokes images of the roofs of shrines, while the decision to support the emphasized cover of the arch approaches the spatial harmony of the wooden beams and columns of Japanese wood buildings. In 2000, at a similar exhibition, Peter Zumthor's wooden Swiss pavilion was widely discussed. In this object, the author, using the motif of Swiss-style log walls as the composition's basis, interpreted it in his own way to create a contemporary pavilion space that conveys harmony with the nation's past. These objects, however, do not feature any obvious characteristics of their country's historic architecture; they have adopted specific images and allusions, the substance, as signs that, presented in contemporary architectural forms and applied to a contemporary function, are compromises or midpoints between obvious markers of the application of "historical-traditional" and completely new "individual creation" discussed in these cases.

Among other international examples of the creative combination of traditional wood morphology and contemporary architecture, Imre Makovecz's works are worth mentioning. Built on Mogyoro Hill in Visegrad, Hungary in 1978, this architect's camping complex and rest center expertly combined the interpreted images of traditional wooden architecture with a personal architectural style, acquiring an unusual contemporary architectural shape that evokes the oldest wooden structures of Hungary. The architect acknowledged that his design for this group of buildings was based on his analysis of folk art.6 Makovecz demonstrated that contemporary wooden architecture can indeed be based on the textures of archaic, traditional, and even animal forms without direct imitation, through allusions that grant poetry and a distinctive mysticism to new works. His ski lodge at Dobogoko, where a circular space covered in wooden boards brings animal hides and fish scales to mind, can be considered a work of this nature.

When speaking of mystical shapes in contemporary architecture, one must also mention the architect Renzo Piano, who accomplished a unique synthesis of high-tech and traditional architecture in the Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Center building in New Caledonia. In particular, it was the traditional wooden house roof, characteristic of the local Kanak culture, that he "translated" into his technological architecture's language in a new, original building that represents the Kanak culture's longevity and symbiosis with nature.7 The building is designed so the tall convex openwork wooden volumes are not merely a compositional accent, but an original climate regulation system, providing protection from the winds off the Pacific Ocean. In the architecture of this building, Piano speaks in signs, using the indigenous buildings' rounded forms, their lightweight construction, and their openness. The building's design has become a textbook example of contemporary architecture in which innovative forms convey keenly observed features of the local culture.8

Successful, well-regarded examples of the synthesis of traditional morphology and contemporary architectural trends in ecclesiastical wooden architecture can be found in the Scandinavian countries. A reconstructed church on Finland's Pyha-joki River is an exceptional example. Insufficient documentation on the location's earlier shrine was the incentive to design a new building of contemporary minimalist form and ordinary construction, but with the outward aspect of old local church-es.9 A church in Jyvaskyla, built according to the design of Las-sila Hirvilammi, falls within a similar creative conception of works based on an interpretation of historic wooden architecture. A shingle church designed by Marta and Lech Rowinsk, on the bank of the Wisla in Tarnow, Poland, is also worth mentioning. Traditional folk architectural motifs are not copied directly; instead, the architects aim for the geometric relationships of building forms, restraint of expression, and sense of moderation typical of traditional wooden architecture. The use of historically linked local materials allows us to consider the buildings under discussion as more than just mere examples of contemporary architecture, but see them as contemporary architecture containing meanings expressed through metaphors, signs, and allusions, a connection with what once was, and as a more solid base for the past and the future.

The problem of applying the morphology of traditional wooden architecture is relevant to many architects' practices in the design of smaller or larger residential or public buildings, their interiors, auxiliary structures, and even minor architectural elements, such as fences or benches. Questions of professional solutions are particularly clear when there is a context of historic wooden architecture nearby, or when the artistic expression of wood manufacture is important to the construction material of the other buildings' architectural character and form.

In

2002, through the prism of contemporary functional requirements and

modern architectural and construction possibilities, Pritzker Prize

winner Zumthor subtly interpreted the particularities of historic

wooden houses with his Luzi House, set in the Swiss Alps. The

traditional Swiss mountain house is distinguished by its monumental

form, massive walls of thick logs, small openings, and roofs with low

slopes. As the basis for the composition of the newly designed house,

Zumthor took the proportions of historic residences - building height,

width, length, and roof slope - but used contemporary elements for the

form's constituent parts. This led to visually narrow projections from

the main volume that recall notched log corners, large oriel windows

and balconies, and the structure of the lightweight roof, seemingly

separate from the structure. In 2009, Zumthor built a structure with a

similar aesthetic in Leis, Switzerland. This building has a form,

height, and roof line similar to those of neighboring buildings.10 The

harmony in these new buildings creates a smooth length of walls with

frameless window openings, a unique contrast to the traditional rough

log buildings, in which the window openings are framed and also divided

into lights.

Creating

harmonious relationships between

traditional wood morphology and neighboring new buildings is not an

easy task, but a frequent one for an architect working in countries

with a deep tradition of wood architecture. In the city of Porvoo,

Finland, the new wooden buildings in the quarter on the right bank of

the river adopt what is best from the Old Town on the opposite side of

the river to the north. The adopted elements include the size of the

buildings, the scale of their facade details, the range of color, and

the relationship between building height and the width of the street.

In this example, the search for a relationship between old and new

wooden architecture is facilitated by distance - since the Old Town and

the new quarter are separated by a river, the harmony of their

composition or the professionalism of their design does not arouse

passionate discussion. It is a different matter in the Old Town of

Hango, where modern wood architecture adjoins historic wooden buildings

making up a mini-quarter. Here, the juxtaposition of old and new

architectural details, their harmony, and the impact of aesthetic

choices are clearly displayed. In this resort on the Baltic Sea, in the

quarter between Torggatan and Korkeavuorenkatu Streets, the standing

structures with apparently identical proportions differ in the

particulars of their age and details. In the aesthetic of the exteriors

of older traditional buildings, large-scale windows and tall doors

dominate the flat walls, and a sense of scale is created by the window

lights and the color and relief accentuation of the wall corners and

lower window lines. In the new building next door, some of the

functional parts of the doors and windows are considerably smaller, and

in an attempt to recreate the typical historical spatial harmony,

larger openings are simply marked by wall color. Despite the

architect's artistic intention, the composition's variation, its

"contemporariness," with various-sized windows and dormers on the roof,

looks like a superficial imitation of the neighboring existing historic

wooden buildings, which are consistent in architectural style.

These examples show the boundary between a professional interpretation and its mutation into a not-particularly successful imitation is a narrow one. Proportions echoing the superficial context are not of their own accord a guarantee of success, if the totality of architectural detail is not mastered. The interpretation of contemporary forms of common elements requires a more careful study of traditional forms, an understanding of basic connections, and the most important principles of composition.

In Lithuania, which has a long tradition of wood architecture, some contemporary wooden structures, in striving to find a connection with ethnicity and tradition, acquire an emphatically commonplace, primitive presentation of poor aesthetic quality. It is impossible to perceive any sign in these structures that the architect took an interest in the forms of traditional wooden architecture and, having found them, used them creatively in a new structure. It is interesting that buildings with this kind of mediocre expression even appear in city centers or on urban main streets, discrediting the legacy of wood architecture and wood as an architectural material. As Vilnius examples, one can mention the farmers market on Ukmergės Street or the Winter Fair stands in Odminių Square. This creates the impression in the cities that traditional village architecture, wood architecture, is equivalent to plank barracks or temporary sheds.

Society's image of a wooden building as a lowly auxiliary structure with questionable ethnographic characteristics is confirmed by the products some Lithuanian construction firms offer in their advertising brochures, retail outlets, and yearly building shows. The owners of Lithuanian tourist farms often buy these and similar products, thereby unintentionally adding to a distorted understanding of wood architecture in the society.

The above examples show that, in Lithuania, the use of traditional wood architectural forms in new wooden buildings is sometimes treated more as a question of the employment of unimportant superficial visual resemblances rather than as a serious problem of architectural craftsmanship.

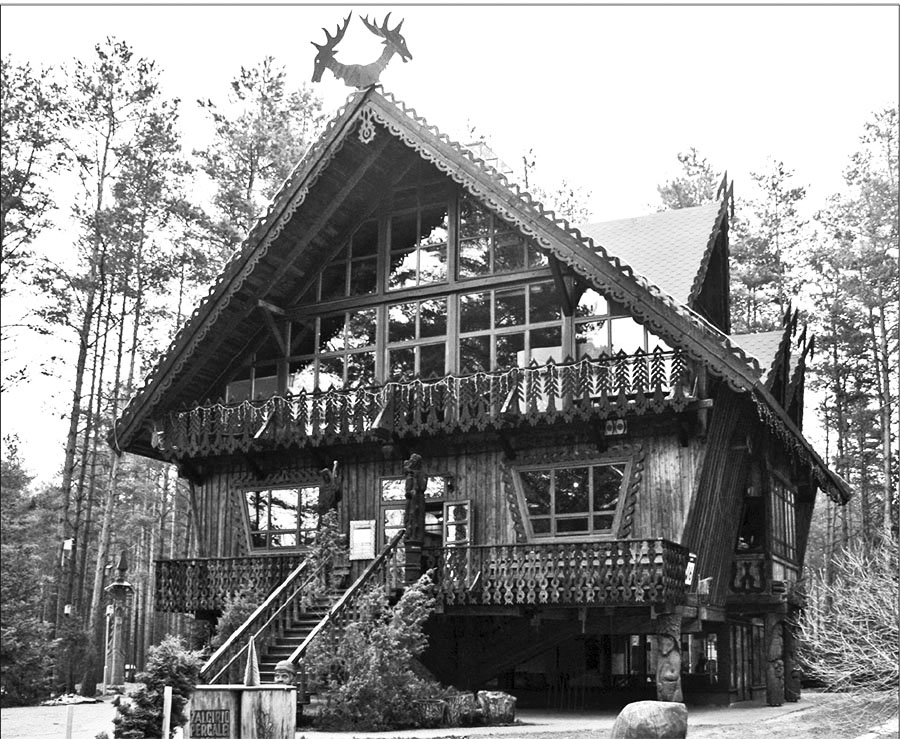

Among the Lithuanian buildings of this type is the museum "Girių aidas" (Woodland Echo), built in 1971. Laima Laučkaitė has called this building a wooden artifact, characterized by Soviet-era folk art, folklore motifs, traditional peasant construction, and elements of contemporary architecture and organic nature.11 The architecture of this wooden building is notable for its great variety of forms and details. The raised part of the building is supported by a modern wood-peg structure, "assisted" by carved columns, the "legs." Parts of the exterior walls are inclined, coordinated on the main facade by windows that narrow towards the bottom. The windows are uniformly framed by gingerbread that crudely resembles traditional window decoration, and a large pseudo-modern glass wall is used in place of the gable panels. The peak of the main gable is decorated with moose heads, while the dormers are topped with forms resembling axes. The exterior reminds one of a witch's house or the like in a fairytale book. The ethnographic architecture presented here is excessively distorted, overdone, with exaggerated proportions. Unfortunately, this building, designed and built by foresters, became famous and attracted visitors from all over the Soviet Union, and continues to be of interest today.

|

| The museum Girių aidas in Druskininkai, designed by Algirdas Valavičius in 1971. |

The demand for "attractively" presented traditional wooden architecture is alive in today's independent Lithuania. The log restaurant Bajorkiemis, built in 2002 along the Kaunas-Vilnius highway, without a building permit and according to the owner's vision, was particularly popular.12 The building, which burned down in November 2012, was considered a fairly accurate copy of the Blinstrubiškis manor, built around 1740 in Žemaitija. To attract visitors, a similar building was attempted not far from Vilnius, on the road to Trakai; but in this case, the Blinstrubiškis principles were not scrupulously followed. The building's volume was much expanded: there were only six windows on each side of the main entrance porch of the original manor, but in the new building, there are eighteen. The porch pediment is also pretentiously finished, incorporates an oval window, and has a more plastic shape. The motif of the design of the entrance pediment is used to decorate the dormers. In this case, it is debatable whether the idea of applying a historic building form to contemporary needs applies to deforming it and incorporating details not characteristic of the original. Even nonprofessionals notice this structure is excessive in scale, inflated, and uncomfortable. It is judged an unsuccessful imitation of a farm manor, misinforming the visitor about the particulars of this type of Lithuanian wood architecture.

|

| The restaurant Trakų Dvarkiemis on the Vilnius-Trakai road, designed by Algirdas Mažeika and Gintautas Remeika, 2006. |

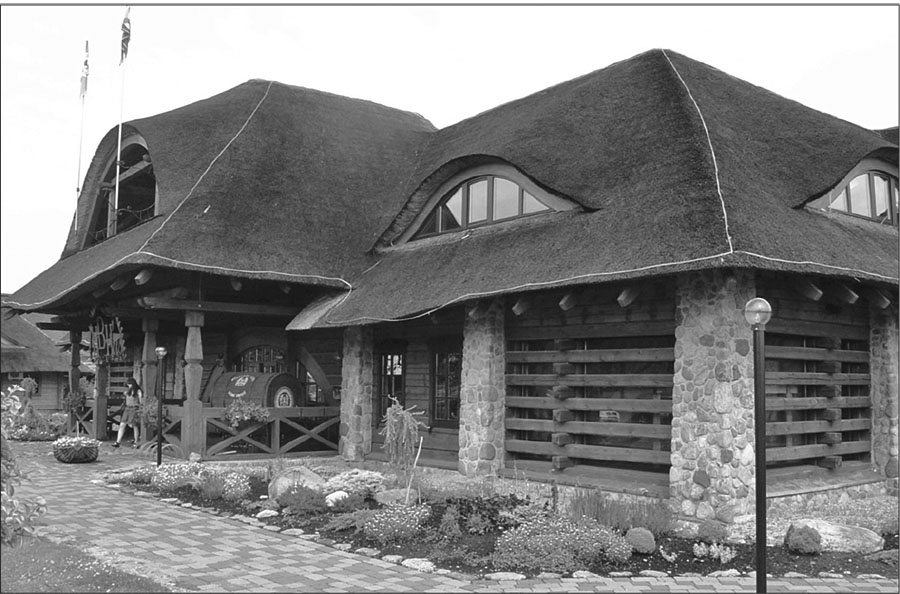

The restaurant Žaldokynė, now called HBH, was built in 2005 along the road to Molėtai near Vilnius. In its wood construction, the first floor is "reinforced" by brick and stone buttresses, and covered with a massive straw roof typical of Žemaitian ethnographic farm structures. The building is entered through a porch covered with a raised three-part roof of the same type, supported by wood columns, and pierced by an arched dormer. The building is a pastiche of various farm, factory, and residential building traditions. In terms of composition, it contributes nothing of value to the art of contemporary architecture and uniquely discredits Lithuania's ethnographic wooden architecture, noted for its aesthetic harmony, concord, and functionality.

|

| The restaurant HBH on the Vilnius-Molėtai road, 2005. |

As

Algimantas Mačiulis asserts, "imitation was always architecture's

scourge." In his opinion, folk architecture's essence manifests itself

in folk art's deep layers and complex semantics, not in the mere

collection of its outward decorative motifs. Among the imitative,

cliched interiors Mačiulis studied, he includes spaces formed by wood

construction and detail. Early interiors of this nature in Vilnius, in

his estimation, include the restaurant Medininkai, where one of the

interior accents is a massive wooden gallery with banisters that

resemble a castle parapet. As examples from recent years, he mentions

the Marceliukės Klėtis inn on Tuskulėnų Street and the Čili Kaimas

restaurant on Vokiečių Street, in which the wood construction and

detail are essentially decorative elements that caricature traditional

architecture's integrity. One must agree with Mačiulis that rustic

interiors shoved into modern architecture, into new commercial centers,

clash with their style.13 Interior

projects that imitate Lithuania's rural style are a unique genre of

architecture in which designers apparently allow themselves to behave

freely, thoughtlessly manipulating traditional wooden architectural

forms without paying sufficient attention to traditional proportions or

the unity and meaning of the details.

Nevertheless, examples of

the coordination of traditional morphology and contemporary

architecture can be found in Lithuania. One may consider the

reconstruction of a residential house in Vilnius's Žvėrynas

neighborhood, designed by Gintautas Natkevičius and associates, as an

example of an appropriate architectural solution. The valuable, visible

historical wooden house's architectural shape was carefully recreated

in accord with the historical material, without changing the exterior

detailing. New architectural forms were adopted in the basement and the

interior, where the unique accumulated historical value of the upper

part of the building was not changed or spoiled.14

The designers' respect for and retention of traditional form and

refusal to push contemporary architectural solutions to the fore does

not lessen the aesthetic impact of the project and impresses us with

its expression of inventive thought.

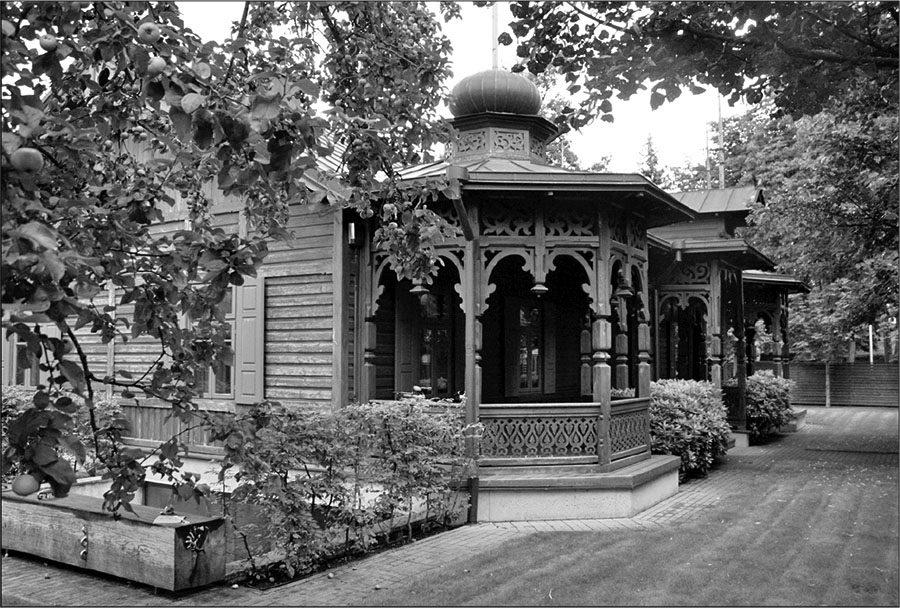

|

| Residential building reconstruction and addition, D. Poškos Street, Vilnius, 2006. Architects Gintautas Natkevičius, Rimas Adomaitis, and Raimundas Babrauskas; sculptor Algimantas Šlapikas. |

In some cases, interesting results are achieved with a more radical reconstruction and recreation of traditional forms on more modest wooden buildings. Alvydas Šeibokas's reconstruction of an early twentieth-century wooden house on Tiškevičiaus Street in Panevėžys can be mentioned as an instance. The architect was not afraid to change the form of the roof, to mount sliding wooden shutters on the facades, or to combine the details of openwork wooden blinds with blank surfaces created from flat wooden planks. The reconstructed building acquired a contemporary architectural character. On the other hand, with its general shape, proportions, and the scale of the details, it remained related to the surrounding urban wooden buildings. In this case, it is clear the designer chose to solve the structure's functional and aesthetic problems by essentially and suitably forming the building's shape anew.

|

| Reconstructed wooden building on Tiškevičius Street, Panevėžys; architect Alvidas Šeibokas, 2006. |

In all probability, the most pressing problems in combining traditional form and contemporary architecture's requirements arise when building new or renovating old wooden structures in protected areas. In 2008-2009, in a series prepared by the Ethnic Culture Preservation Commission, an attempt was made to define the basic characteristics of historical wooden structures and to clearly indicate some possible means of balancing the old and the new. An attempt was made to establish theoretical prerequisites for successful architectural solutions. The scholar Aistė Andrušytė and her coauthors observed that it was not just the embellishments and details that must suit a traditional shape, but also the configuration of spaces and the combinations and proportions of volumes.15 Writing about the building of new structures in Aukštaitija, Rasa Bertašiūtė and her coauthors state that harmony is possible in the combination of the modern and the ethnographic, when new construction materials, along with contemporary ecological and economic considerations, are linked to those properties of the building and the structure of the building itself that reveal the area's ethnographic particularities. They recommend observing the commonalities in the centuries-old tradition of wood construction. Interestingly, in this study the authors do not reject the possibility of preparing entirely new projects that are not typical of the local architecture, but can be integrated with the existing surroundings via the principles of contrast or nuance. They do, however, emphasize that new structures should not become overbearing, and their solutions should complement the existing landscapes and buildings.16 The essentials for putting theory into practice can be seen in the 2010 publication Kaimo statyba: Rytų Aukštaitija (Village Construction: Eastern Aukšaitija), in which the farmstead building projects presented, as the authors of the text and the projects assert, strive to integrate a contemporary village lifestyle with the forms of long-established farmsteads, with characteristics representative of the area that reflect the worldview, lifestyle, and circumstances of its people.17 In the projects this publication offers, it is obvious that efforts to, in essence, change the layout or form of at least several details in an entirely traditional building's structure frequently lends the composition a suggestion of the imitative quality discussed earlier. Examples of this are the joining of two customary windows into one in the "Kovas" project, or the doubling of the fancy front-hall window in the "Spalis" project. In 2012-2013, this collection of designs was enlarged by publications devoted to other ethnographic regions of Lithuania.18 The tremendous amount of work the authors put into this (163 projects are presented, the majority of them wood architecture) did not dispel a dispassionate observer's doubt that the inhabitants of a protected area should build the exact same house and farm buildings their forefathers did, ignoring today's functional necessities and the natural urge for technological or aesthetic progress lurking in human nature. Although, in the majority of the projects, the authors attempt to apply present-day planning to living space, incorporating new functions and structural improvements to older building types, in many cases, they try to keep the building's exterior "as it was earlier." This is a dangerous move towards the creation of an imitative, decorative architecture. These project catalogs drew criticism from some Lithuanian architects, who observed that the project solutions do not suit the times nor consider the realities of present-day rural life, and the buildings resembled cliched, faux architecture.19

All the same, the ability to successfully rely on traditional form in one's work and produce an artistic result that is valuable from an architectural standpoint depends on talent, not just theoretical knowledge. A lucid position and confidence on the part of the designer is obviously extremely important to avoid the conflicts between traditional form and imitation in wood architecture. A good understanding of the composition and meaning of the particulars of the desired traditional form, like mastering the rules of an established game, allows a successful contemporary result, one in which the forms of the past are neither distorted nor caricatured. Another successful design principle, which has earned the greatest appreciation among professionals, is when older traditional wooden architectural morphology is interpreted by means of adopting the substance and basic proportions of the forms, and marking and coding traditional characteristics by means of contemporary architecture and technology.

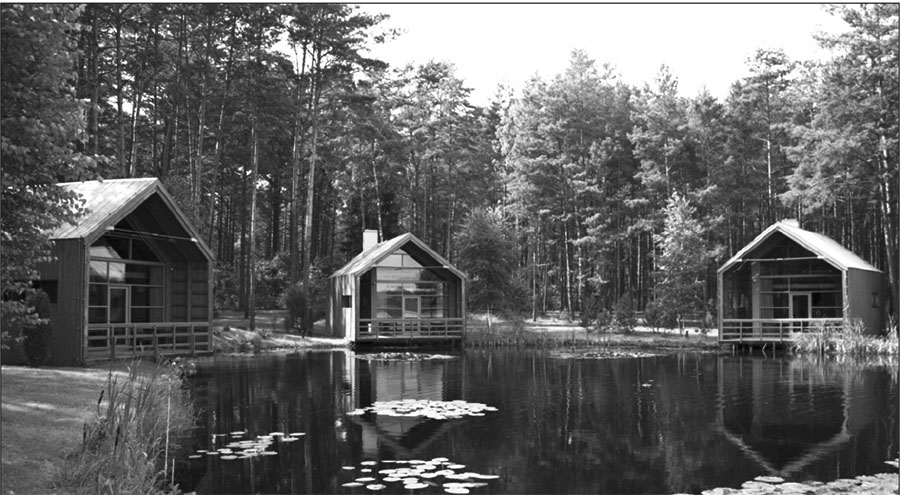

In this respect, the architectural group Arches, whose resort project, built at Lavyso Lake in 2008, was designated one of the best works at the show "Žvilgsnis į save 2008-2009" (A Glance at Ourselves 2008-2009), could be mentioned here. This interesting project is a reconstruction of the resort homes Nakcižibis (Night Glow), nestled in a pine forest. As the authors assert, the very name of the buildings, the protected ethnographic village nearby, the surrounding pines, and the lake sprawling alongside inspired the solution. A composition of compact volumes distributed among the pines was required, hence the openwork volumes that gleam at night and are reflected in the water. These were meant to be scattered among the natural surroundings and melt into them, to convey the lines, ease, and grace of the tree trunks, and to appear as translucent as the mass of the pines. Natural and traditional materials - wood, wood chips, and lattice - are used in the buildings' construction. By separating the volumes of the resort homes and dispersing them, they sought to create the necessary uninterrupted connection with the natural surroundings, as well as privacy for the occupants.20

|

| The new resort buildings next to Lavyso Lake, designed by the Arches firm, 2008. |

Leonardas Vaitys, discussing this project in the press, first notes the absence of detailed ethnographic manifestations. According to him, the buildings' scale, form, and decorative materials seem to allude to traditional farmstead building principles, although the fine details of their facade finishes do not venture further towards ethnography. He then concedes that the composition's joining of all the buildings into a whole is excellent.21 By not copying traditional decorative details verbatim in the reconstructed buildings, the architects avoided the dangers of imitation. In the common architecture of the reconstructed and new buildings, wood architecture's traditional markers - in particular, its forms, proportions, and the characteristics of its materials - are masterfully united with contemporary aesthetics and functional solutions into a single whole. The accented windows, doors, and roof details beloved of other reconstructed traditional buildings are here designed without any special decoration, by means of minimal contemporary aesthetics oriented towards function.

Conclusion

Imitation in contemporary architecture results when crude, banal, stylistically distorted design solutions appear in a directly repetitive universe of traditional forms and elements. Another variant is when parts and elements typical of ethnographic architecture are incorporated into a structure that is modern in its expression. In imitative architecture, ethnographic architecture is frequently offered as superficial window-dressing rather than a functional necessity. Imitation in Lithuanian wooden architecture is essentially considered a negative phenomenon.

There are two methods of using traditional forms in contemporary wooden architecture that can be positively evaluated. The first is an exact, detailed recreation of a traditional wooden structure, using accurate research materials. Essentially, the motivation for this method can only apply when reconstructing deteriorated old wooden buildings. The second method is to mark or code forms characteristic of traditional architecture, the aesthetic particulars of its elements, its principles of construction, and its substance, by using new design language. In this manner, a functional, aesthetic object of technologically oriented architecture is created that enriches the connection with tradition and cultural uniqueness without appearing like window dressing.

Notes:

1 Dethlefsen, Rytų Prūsijos kaimo namai.

2 Banelis, Gimbutas, "Lietuviškos architektūros klausimu."

3 Banelis, Lietuviško vasarnamio projekto konkursas.

4 Minkevičius, Architektūros kryptys užsienyje.

5 Gimbutas, Lietuviškos architektūros klausimu.

6 Makovecz, "Epuletek."

7 Pryce, Architecture in wood, 320.

8 Lehtimäki, et al., Renzo Piano.

9 Kasvio, et al., From wood to architecture.

10 Zumthor, Zumthor: Spirit of Nature Wood Architecture Award 2006.

11 Surgailis, Mediniai Druskininkai, 176.

12 Dargis, "Gandai ir mistika," Tvirbutas, 'Bajorkiemio' savininkas viliasi išsaugoti nelegalius pastatus. "

13 Mačiulis, "Kičo apraiškos," 167-172.

14 Liutkevičienė, "Medinė Vilniaus karūna," 18-23. 54

15 Andriušytė, et al., Dzūkijos tradicinė kaimo architektūra, 104.

16 Bertašiūtė, et al., Vakarų aukštaitijos tradicinė kaimo architektūra, Bertašūtė et al., Rytų Aukštaitijos tradicinė kaimo architektūra.

17 Bertašiūtė, et al., Kaimo statyba: rytų Aukštaitija.

18 See Bertašiūtė, et al., Kaimo statyba: Dzūkija (2012); Kaimo statyba: Vakarų Aukštaitija (2013); Kaimo statyba: Suvalkija (2013); Kaimo statyba: Mažoji Lietuva (2013); Kaimo statyba: Žemaitija (2013).

19 Leitanaitė, "Naujai architektūrai kaime - tik šimtmečių senumo idėjos?"

20 Arches, "Projektai/Rekreaciniai."

21 Vaitys, "Poilsinė prie Lavyso ežero," 70-78.