Copyright © 2014 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Editor of this issue: Daiva Litvinskaitė

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2014 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume

60, No.3 - Fall 2014

Editor of this issue: Daiva Litvinskaitė |

Communist Propaganda, Artistic

Opposition, and Laughter

in the Lithuanian Satire and Humor Journal Šluota, 19641985

NERINGA KLUMBYTĖ

NERINGA KLUMBYTĖ is an Associate Professor of Anthropology at Miami University, Ohio. Her articles have appeared in American Anthropologist, American Ethnologist, Slavic Review, East European Politics and Societies, and other journals. She is a coeditor of Soviet Society in the Era of Late Socialism, 1964-85 (with Gulnaz Sharafutdinova), 2012.

Abstract

Šluota (The

Broom), a popular Lithuanian journal of humor

and satire in late Soviet Lithuania, was a journal of Communist

propaganda intended to follow Soviet agendas and contribute

to the building of Soviet society. The journal, however, also

housed forms of artistic opposition and renegotiation of official

values and ideologies. Through the exploration of ethnographic

and archival data, my article discusses the contributions artists

made to the journal, as well as the meaning and social significance

of their work. I argue that Šluota artists humor contributed

to the Soviet state agenda to create a Soviet society and educate

its citizens. At the same time, however, many artists opposed

Soviet state authority and renegotiated Soviet ideologies

through the use of Aesopian language; silence about politically

relevant topics like religion; artistic style, which challenged the

Soviet art canon; nationalist recontextualization, which placed

responsibility for various problems on the Soviet state; and

participation

in officially disapproved actions, such as drinking at

work. Like Šluotas artists, readers participated in shaping and

renegotiating Soviet values and ideologies. Their engagements

were neither an example of clear collaboration, nor of open resistance,

but rather a close interaction with power through dialogue,

negotiation, acceptance, and rejection.

Šluota, a Lithuanian journal of humor and satire, is still positively remembered by many who lived in Soviet times. Why did readers like it? Wasn't it one of the journals that contained Communist propaganda? Were people able to read between the lines, ignoring the propaganda and searching for something they could laugh at? What was Soviet humor like in Lithuania? Goda Ferensienė, who worked in the literary division of Šluota in the 1960s, commented that my extensive use of "socialist" in a 2011 article about Šluota was out of place: "We were free," Ferensienė argued. But the Communist Party members, who constituted half of Šluota's employees and had the leading positions, claimed at their Primary Party Organization (PPO) meetings that "Every word of a satire has to be devoted to the cause of the Communist Party and its ideals"1 or that "Laughter is also politics. If people laugh [when they read Šluota], it means they are happy with our life and the system"2 or "Our journal is political. We all do political work."3 Ferensienė's comment about Šluota indicates the apparent paradox this article addresses - to be a Soviet citizen did not necessarily mean identifying with Soviet state agendas and perceiving oneself as "Soviet" or "socialist." In this article, I address the above questions and argue that Šluota's humor contributed to the Soviet state agenda to create a Soviet society and educate its citizens; but at the same time, its artists opposed the Soviet state's authority and renegotiated Soviet ideologies.

This article is based on my research on political culture in late Soviet Lithuania carried out in the summers of 2008-2013. It relies on interviews with several Šluota artists, journalists, and writers, Šluota's readers and contributors, as well as the reports and minutes of Šluota's PPO meetings in 1960-1979.4 This article focuses on artists' roles and contributions to the journal, as well as the meaning and social significance of their work, which includes cartoons, illustrations for literary pieces, and cover art.5

The History of Šluota

Šluota was first published illegally in 1934 by artists and revolutionaries from the Lithuanian Communist Party in the Kaunas region. At that time, Lithuania was an independent presidential republic, with Kaunas as its provisional capital. The title of the journal and the images on its covers defined its Communist agenda: to sweep unwanted bourgeois elements and values out and to purify society from the ills of militarism, capitalism, and clericalism.6 The first illegal issue had sixteen pages, as would issues published legally in Soviet Lithuania. Seven issues of Šluota were published between 1934 and 1936, when publication was discontinued, most likely due to the persecution or relocation of the journal's major contributors.7

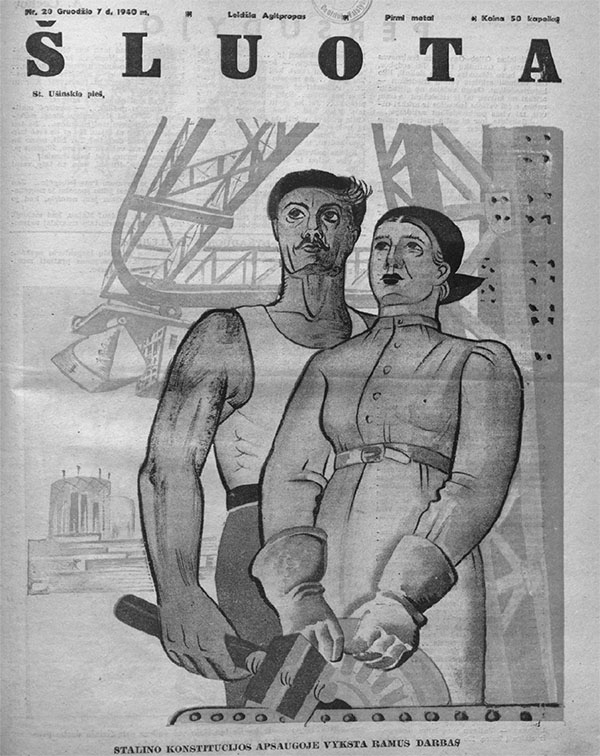

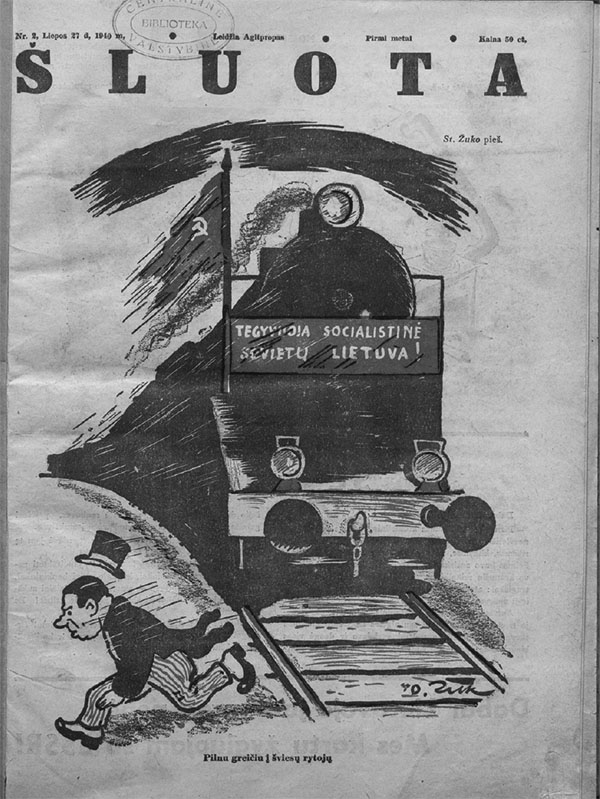

The first legal edition was published on July 12, 1940, nine days before Lithuania officially became a new member of the USSR. Šluota published twenty-three issues in 1940 and twenty-five in 1941. These issues celebrated the freedom of the working people and peasants. They lampooned former and current enemies of the people, including speculators, imperialists, capitalists, clerics, landlords, the rich, intellectuals, and bureaucrats. Šluota critiqued various problems of everyday life, such as laziness, procrastination at work, wastefulness, irresponsibility, selfishness, and alcoholism. Work, specifically socialist work in a collective, and commitment to the public good and a socialist future, were celebrated and contrasted with prior labor relations based on class differences. The issues published in 1940 and 1941 critiqued Smetona's bourgeois regime, used Communist rhetoric, and actively promoted political agendas geared toward building a new socialist society (Figs. 1 and 2). The journal shut down in 1941, when editor-in-chief Stepas Žukas fled Nazi-occupied Lithuania.

|

|

| Figure

1. "Under the guardianship of Stalin's constitution, peaceful work

continues," by Stasys Ušinskis,

issue No. 20, 1940, 309.

|

Figure 2. "Let socialist Soviet Lithuania

live! Full speed towards a brighter tomorrow," by Stepas Žukas,

issue

No. 2, 1940, 17.

|

In 1956, the Central Committee of the Lithuanian Communist Party resurrected Šluota and moved its headquarters to Vilnius. Juozas Bulota became the first editor-in-chief and remained in this position for almost thirty years, until 1985. The post-Stalin era Šluota was very different from its predecessors. The fight against imperialism was restricted to some assigned pages or special issues celebrating important events, such as the thirtieth anniversary of World War II. The main characters in earlier editions, such as landlords, the rich, the clergy, and kulaks, disappeared from the issues of 1956 and later. While in 1940 and 1941, blame for social ills had been directed predominantly outside one's imagined socialist community (i.e., towards the capitalists, imperialists, enemies of the new socialist state, and the bourgeois class), now the journal turned its focus inward (i.e., we, the workers, are the ones who procrastinate, pilfer from the workplace, drink, and are selfish). Moreover, a new socialist class of bureaucrats, managers, factory, state, and collective farm directors, and other new elites (but not Party or government authorities) was also lampooned in the pages of Šluota. The journal also continued to criticize social disorders addressed in the 1940 and 1941 issues, such as lying to officials, abusing the public sphere for private interest, or procrastinating at work. By now, however, the laughter was much lighter and lacked its former revolutionary seriousness.

|

|

Figure

3. The building on the corner is the former editorial headquarters of

Šluota. Bernardinų Street 8, Vilnius.

Photo

by the author.

|

Although the topics covered in 1956 and later issues share many similarities with earlier editions of the journal, there is a noticeable shift, not only in the target of criticism, but also in their tone - Šluota's motif of purifying and cleansing society disappeared from its pages, but not from Šluota's PPO discussions. It is likely that in the 1970s and 1980s few readers even knew the origin of the journal's name. By that time, many readers, journalists, and writers would likely smirk at descriptions of Šluota's former revolutionary spirit, since few of them could identify with its former revolutionary agenda. For Šluota's artists in the late 1960s and 1970s, a new elite group of professionals, the journal was an outlet for art, not revolution. Gone was the revolutionary critique of social vices and the firm belief in a bright future and the perfection of society.

The popularity of Šluota was reflected in its circulation, which rose from twenty thousand copies in 1956 to over one hundred thousand in the 1980s.8 Thus, at its peak, there was approximately one copy per thirty inhabitants. Although the actual number of copies sold is unknown, this journal was widely known and read in the 1970s and 1980s. It was the only journal of humor and satire in Lithuanian and, in Lithuania, much more popular than the pan-Soviet and Russian Krokodil. Moreover, Šluota was profitable, unlike many other newspapers and journals, such as Tiesa (Truth) and Komjaunimo Tiesa (Komsomol Truth). It did achieve recognition in the USSR and eastern Socialist Bloc countries (see below).

Readers' memories indicate the overwhelmingly positive reception of Šluota. During my interviews, just mentioning Šluota elicited a warm smile followed by pleasant memories of reading, collecting, purchasing, and sharing it with others. Some of Šluota's folklore was still alive in the late 2000s, and I heard several people quoting Šluota's jokes during my summer research in 2009.9 Indeed, not everything in Šluota was equally liked, but the content was diverse enough to satisfy most readers.10

In 2008, the writer and satirist Jurgis Gimberis expressed regret that Šluotas laughter did not survive post-Soviet times.11 After independence, Big hopes. Sacred things. Sacred slogans. There was no place for laughter, critique, satire. How can you cut the limb youre sitting on? According to Gimberis, Šluota in Soviet times was very balanced:

There was serious and simple, vulgar and intellectual humor. Anything you wanted. Now, it is hardly possible to revive it. Maybe thats why I am not interested in humor anymore. I almost dont write. I earn money translating foreign literature.12

Kęstutis Šiaulytis, a Šluota artist and editor, argued that Šluota was "a publication of a sophisticated humor culture. Now if people laugh, they most often laugh at all kinds of nonsense."13 Pleasant smiles and memories of the readers', as well as artists' and writers' commentaries, indicate that certain forms of Soviet-era laughter, even if they were a means of Communist propaganda, were also their own.

Šluota - A Weapon of Class Struggle

Humor can be very powerful. Lenny Bruce's performances in the 1950s and 1960s liberated nightclubs by turning them into "America's freest free-speech zones."14 Twelve cartoons on the prophet Mohammed, published in 2005 by Jyllands-Posten, a Copenhagen newspaper, provoked a harsh response from the governments of Muslim countries, a boycott of Danish goods, and death threats against the cartoonists.15 In early Soviet Russia, laughter was "a weapon of class struggle, a mechanism of social control, an instrument of social cohesion, a means of distinction, or a tool of self-improvement."16 Lenin and Stalin, like Mao and Hitler, allowed no laughter at the expense of themselves or their regimes.17

Post-Stalin

Soviet leaders were well aware of the political and ethical functions

of humor and satire. Nikita Khrushchev claimed, "Satire is like a sharp

scalpel; it reveals human tumors and quickly, like a good surgeon,

takes them out."18

Lithuanian journalist, educator, and satirist Jonas Bulota, a brother

of Šluota's

chief editor Juozas Bulota, stressed when he wrote in 1964, "Šluota

has to speak about serious things in a cheerful way. It has to laugh at

various ills that hinder our march to the bright Communist future.

Healthy laughter is the best medicine against all kinds of ills and

imperfections."19

Šluota's

Communist editors reinforced this agenda at their meetings, pointing

out that Šluota

is a journal of Communist propaganda and its role is to fight for the

working class, the moral standards of Soviet society, and the

shortcomings "still emerging" in agriculture, industry, and everyday

life.20 Šluota

aimed to cover the majority of aspects of socialist life, from the

construction of cattle barns to the negative treatment of retired

collective farm workers, from corruption and theft to work hygiene and

order. In designing action plans and in their engagements, Šluota's

editors had to respond to pan-Soviet Party Congresses, local Lithuanian

Communist Party directives, or Communist leaders' speeches.

Šluota

also provided a platform for grassroots involvement in building

society, that is, for criticizing, complaining, reporting on

authorities or neighbors, and condemning collectively and individually

disapproved actions.21

Numerous letters came from people from all over Lithuania, some of them

from the so-called aktyvai who collaborated with Šluota

periodically. Although yearly data do not exist, available information

provides a sense of readers' very active involvement. In 1963, the

office of correspondence received 2,234 letters, 230 of which were

published.22

In 1964, this office received 1,950 letters,23

and in 1977, 2,217. (1977 data for Jan. 1 through Dec. 1).24 In 1977,

every issue of Šluota

used about ten letters from readers, either publishing them or using

them indirectly in satires or jokes.25

The journal employed several full-time editors and journalists to work exclusively on reader's letters. For many years, the office of correspondence was successfully headed by Albertas Lukša, who also served several terms as Šluota's PPO Secretary. Every letter had to be answered or transferred to another institution. Moreover, before covering it in the journal, Lukša and others were responsible for checking the accuracy of the complaint, including visiting the site. Not all letters were published in the journal or checked by Šluota's employees. Some were redirected to other institutions, others were unsuited for Šluota, and there were letters that were never answered, despite Šluota's guidelines, which required that all letters be answered.26 Lukša complained about the heavy workload, the problems of accuracy, and the ineffectiveness of the office of correspondence in solving the problem, and argued for the need to check every letter rather than forward it to other institutions.27

By defining its role as a Communist propaganda journal, responding to the Congresses of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and other Communist agendas, and by directly engaging people in building and educating Soviet society, Šluota contributed to the Soviet leaders' aims to build and govern society through nonviolent means. On the other hand, as Ferensienės's comment cited above illustrates, readers and contributors, as well as some of Šluota's employees, did not think they were building a socialist society when they wrote for Šluota or when they read it. Dissociations from "socialist" and "Soviet" indicate the presence of opposition, which coexisted with the journal's Communist agendas. In Šluota, as one of its artists argued in 2013, it was popular to "be against." This opposition, discussed below, reproduced the official Communist values as well as renegotiated and undermined them.28

Laughter and Art

Šluota's artists made a significant contribution to the journal: various cartoons and illustrations constituted around one-third to a half of the content of each issue, and the work of skillful artists contributed a lot to Šluota's success in Lithuania and outside the republic. Šluota employed several full-time artists, but many contributions to Šluota were made by other artists who did not work for the journal full time, like Vladimiras Beresniovas, Andrius Deltuva, Jonas Varnas, Algirdas Radvilavičius, Fridrikas Samukas, Vitalijus Suchockis, Leonidas Vorobjovas, and Vytautas Veblauskas, among many others. According to Šiaulytis, in the 1970s and 1980s there were around sixty artists who more or less regularly contributed to Šluota.29

Although Šluota's archives present very sketchy data on the role of the artists and their contribution to the journal, it is evident that something changed in the late 1960s, a trend that continued into the 1970s and 1980s. Since the late 1960s, Šluota's PPO meeting reports increasingly engage with issues related to Šluota's art and criticize the artists' work. During the late 1960s and 1970s, Algirdas Šiekštelė, Andrius Cvirka, Arvydas Pakalnis, and Kęstutis Šiaulytis worked for Šluota. They constituted a new generation who brought in new artistic ideas, which raised Šluota's PPO's concerns. Many of these new, young artists who contributed to Šluota in the 1970s were graduates of the Vilnius Art Academy, which encouraged experimentation and independence.30 They searched for new aesthetic languages and "felt under the influence of new trends they admired."31 Many of these artists followed Western authors, such as Her-luf Bidstrup, a Danish socialist caricaturist, and Western styles, such as the styles of French authors publishing in the Communist newspaper L'Humanite, which was available in kiosks in Vilnius.32

In the late 1960s and 1970s, Communists at Šluota's PPO meetings complained about "aestheticism," "mannerism," the "modernism" of the artists, and their lack of attention to facts and important everyday issues.33 They noted the absence of strong political cartoons or anti-imperialist and antireligious themes in Šluota's art.34 They addressed these issues in a variety of ways: artists were expected to go to rural areas together with writers to get a better sense of the real life covered in their work;35 artists were also obliged to attend various seminars for political education (low participation was common among both Communists and non-Communists);36 and artists were to receive higher honorariums for anti-imperialist or antireli-gious themes.37 In the late 1960s and 1970s, a recurrent comment in Šluota's PPO annual reports was how unfortunate it was that none of the artists belonged to the Communist Party.38 Šluota's Communists most likely expected Party membership to encourage artists to take more responsibility for representing Soviet agendas in their artwork. In 1979, Bulota impatiently claimed at one of Šluota's PPO meetings:

We must revive contra propaganda. We have to revive political cartoons in Šluota. We have to increase the honorarium for political cartoons and decrease the honorarium for simplistic jokes. Let the authors feel it in their pockets. Internal affairs [of the Soviet state] are also politics. Ultramodernity and attempts to outcompete the West will take us in the wrong direction. We have to denounce the bourgeois lifestyle 39

In the 1970s, I would argue, the artists' successes strongly influenced the future of Šluota's art and departures from PPO's agendas. At that time, Šluota's artists achieved pan-Soviet and Eastern European recognition: their cartoons were republished in different journals of humor and satire;40 they participated in Soviet Union and socialist Eastern European art exhibitions and won prizes;41 in 1974, Šluota won second-place recognition in the USSR for the illustration and graphic design of the journal;42 and Šluota's artists initiated some new aesthetic experiments, such as comic strips.43

Cartoonish Society

In their cartoons, artists addressed a variety of Communist Party agendas and contributed to Soviet state aims to educate citizens, whether through work or family life. As Daphne Berdahl noted, in socialism, productive labor was a key aspect of state ideology and the workplace was a central site for social life.44 Productive labor was also a key aspect of Communist morality. "The Moral Code of the Builder of Communism," the single most authoritative and enduring statement on the nature and content of Soviet morality,45 emphasized hard work and collectivism, among many other moral dispositions.46 Šluota's PPO meetings also emphasized the importance of work: following Communist Party agendas, Šluota was to fight against procrastination, absenteeism, abuse of work discipline, immoral leaders, favoritism, and other work-related issues.47 Poor work ethics, such as dawdling, drinking, and pilfering at work, received considerable attention in the pages of Šluota. Artists criticized and ridiculed workers who called in sick just to stay home, go fishing or take a vacation, or those who used the work place for personal gain. In Rimantas Baldišius's cartoon, a man with a suitcase is walking through a corridor. He says: "I smell coffee; that means everyone is at work."48 Readers got the inside joke, since coffee signified taking a break and socializing instead of working.

|

| Figure 4. "Hey, look, that fella left our

"signature" steak (šnicelis)

in the book of complaints," by

Andrius

Cvirka (Aloyzas Krizas),

issue No. 3, 1975, 10. |

Shortages and favoritism, as well as salesclerks with their hand in the till, poor service, and low-quality goods, defined the Soviet-era culture of consumption and service covered by Šluota. Jokes circulated about the ineffectiveness of complaining about public services. A cartoon by Andrius Cvirka (Fig. 4) shows a way of getting a complaint noticed. Some wary consumers brought calculators to stores and counted everything along with the salesclerks.49 In Valdimaras Kalninis's cartoon there are two sales counters with scales; the bigger counter has a big scale that obscures the smaller counter, so the customer cannot see the small scale. This cartoon invokes the widespread practice of salesclerks giving short change or overcharging. Readers recognized the culture of double standards, where salesclerks adjusted their scales to show more weight than there actually was, while other consumers, usually acquaintances and friends of store staff, were surreptitiously provided with better cuts of meat, cheese, or vegetables at lower rates and weights.

As with work and service, by criticizing marital relations and family and gender issues, Šluota's artists recirculated official social and moral values. Both the Khrushchev-era 1961 moral code and Brezhnev-era moral theories called for the conscientious fulfillment of familial obligations. Writing about the Khrushchev era, Field argued that everyday life seemed dangerously resistant to Communist reconstruction. Various "bourgeois habits" remained, including domestic violence and alcoholism, but also religious practices and the problem of meshchanstvo (snobbishness), which included materialism, small-mindedness, an exclusive concern with family and personal life, and a corresponding lack of social involvement. Soviet moralists condemned individuals who refused to sacrifice personal comfort for the greater good as Communist morality demanded.50

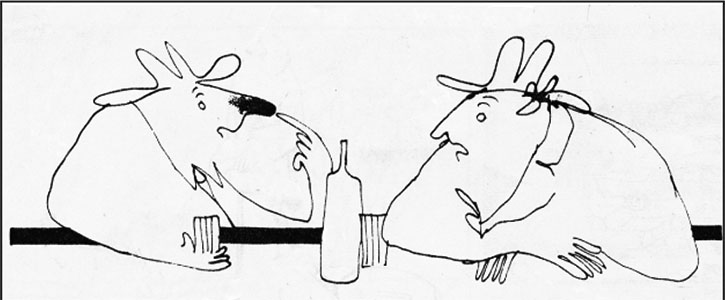

Šluota

portrays men as incurable drunks, while women are devoted fighters on

behalf of the family.51

Some women gossip and crave material goods, but these vices seem minor

when compared to the moral degradation of men. According to one joke,

the best way to get a drunken husband home from a party is to tell him

there is another bottle at home.52

A

cartoon by Andrius Deltuva shows two drivers whose trucks have crashed

into each other. They have a bottle in front of them and appear drunk.

Both men tell the policeman writing up the report that they just had a

few shots to celebrate the fact that they survived the accident.53 Another

example:

|

| Figure 5. "It's red because all of life's

blows land right on my nose," by

Andrius Cvirka, issue No. 8, 1975, 6.

|

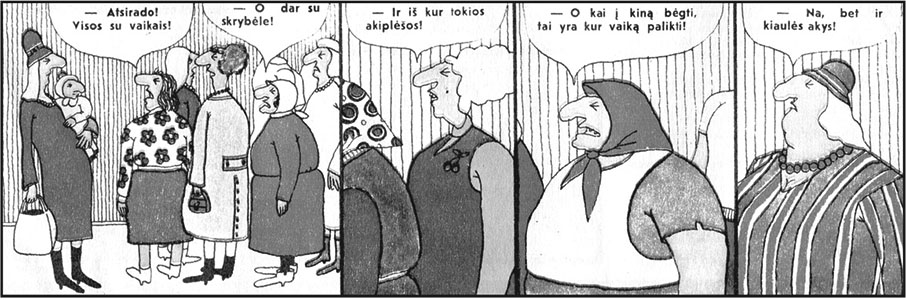

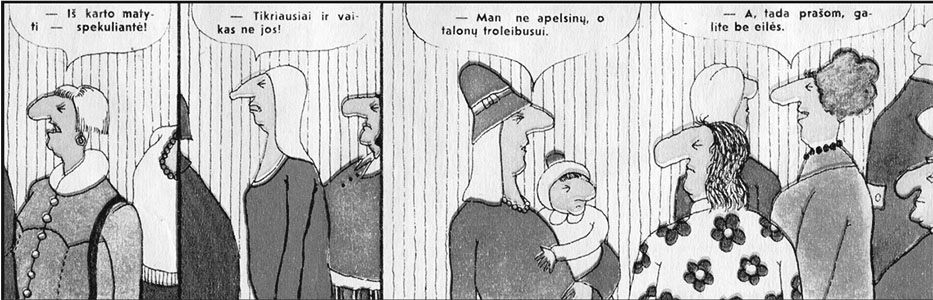

Cartoons advocated warm and caring public relationships, mutual understanding and respect, and openness and sensitivity to others' concerns. Most people did not understand them as "Soviet" or "socialist," even if these themes were propagated from the tribunes of the Communist Party in Moscow. One cartoon, for example, shows a woman carrying a small child in one arm and a bag in another approaching a long line of other female shoppers (Fig. 6). The other women all size her up. This cartoon mocks the women shoppers' inat-tentiveness and insensitivity to a woman with a child. While the cartoon may be read as a critique of the Soviet economy of shortages, it also instructs people to preserve moral values despite stressful shopping experiences.

|

| Figure 6. Woman 1: "Just look! They always have children!" Woman 2: "And what a hat she's got!" Woman 3: "Where do these rude women come from?!" Woman 4: "When they go to the movies, they know where to leave the children!" Woman 5: "She's shameless!" |

|

| Woman 6: "You can see right off she's a speculator!" Woman

7: "That's probably

not her child!" A woman with a child: "I don't need

oranges, I just want a trolleybus ticket." Woman 7: "Oh, then, please, go ahead," by

Vitalijus Suchockis, issue No. 5, 1975, 8-9.

|

Artistic Opposition

As the following discussion will show, Šluota generally, and Šluota's artists specifically, did not follow Soviet ideological prescriptions at all times. Šluota, an active agent of the Soviet state and a platform for socialist education and moral upbringing, was infused with various transgressions that shaped official social and moral orders. The socialist universe in the pages of Šluota was neither an outcome of artists' engaged collaboration with the Soviet state nor their open resistance. It was the outcome of ongoing negotiations, experimentation, and dialogue.

Among

artists, there were multiple creative means of contributing to the

renegotiation of the official social and moral universe. These included

several forms of artistic opposition: secret intentional opposition

targeting the Communist system and its leaders; unintentional

violations of Communist communication codes, such as publishing the

ambiguous cover for Lenin's 100th anniversary that caused the edition

to be destroyed;55

and routinized renegotiation of official norms in the pages of Šluota, like use of

Aesopian language56

to communicate hidden texts.

Writers

and journalists were relatively more constrained than artists, since

visual art was more difficult for the censors and the Central Committee

to understand. Goda Ferensienė and Laima Zurbienė, who were on the

editorial board of Šluota,

related it was much more difficult to hide some plots and meanings in

written works.57

Epigrams and aphorisms were written in Aesopian language, unlike

feuilletons. Writers sometimes came up with generalizations such as

"those in power can do anything." You had to be careful, remembered

Zurbienė, not to make explicit commentaries about the state. A clear

allusion to the local government was necessary if you spoke about

government. For Ferensienė and Zurbienė, Šluota

was a space of creativity, freedom, and self-fulfillment. The state and

the Party were somehow outside their lively everyday work culture,

which was mediated by warm interpersonal relations in the publishing

house. Officialdom was embodied by outsiders like the Central Committee

members who inspected issues of Šluota. The "state" also existed in the

form of rules, regulations, and an irrational bureaucracy, which had to

be publicly acknowledged, and behind which Šluota's writers

carved out a space of normalcy and relative freedom.

There were a number of different techniques of reinter-pretation that contributed significantly to the rearticulations of the Soviet ethical and social universe and constituted a culture of opposition, including: 1) Aesopian language; 2) national re-contextualization; 3) aesthetic rearticulation; 4) silence; and 5) participation in officially disapproved actions, such as drinking at work.

First, Aesopian language consisted of text hidden behind the evident text. The critique of bureaucrats and factory, collective, and state farm directors was consistent with official rhetoric about the prevalence of some shortcomings in socialist society. Šluota was allowed to speak about these topics, as it followed the state agenda to monitor citizens' behavior through popular and moral means. However, there were other hidden texts - texts that extended the critique to Soviet socialism and the Soviet state. Cartoons and stories depicting bad khoziaieva (masters, owners) in many cases built a narrative about the Soviet economic regime being ridden by inefficiency, shortages, and corruption. Various Aesopian presentations violated Šluota's PPO meetings' exhortations to avoid ambiguity, to make sure that the text and subtext were clear to the reader.

Second, national rearticulation, which was also often narrated in Aesopian language, displaced responsibility from "us" to "them," to the Soviet Union or the Soviet regime. Censors, editors, artists, writers, and readers were united in nationalist laughter at the "Soviet" other.58 For example, cartoons and stories about pollution in the 1970s, and especially in the 1980s, coded a negative commentary about Soviet industrialism and pollution. Men dressed in Western-style clothing could indicate the author's critique of the West. However, a reader could see other hidden texts behind the obvious: the Soviet "bourgeoisie," rather than the Western, behaves this way; the pollution is Soviet as well, polluting our country.

The

third form of opposition was aesthetic rearticulation, which challenged

official artistic styles and the Soviet art canon. In 1969, Executive

Secretary Jonas Sadaunykas encouraged artists to follow a direction

that is "realistic, simple, and understandable to every reader," which

was Šluota's

traditional

direction. According to Sadaunykas, artists in 1940-1941 created

realistic and simple cartoons that were understandable to every reader.

He condemned other styles as technically inept:

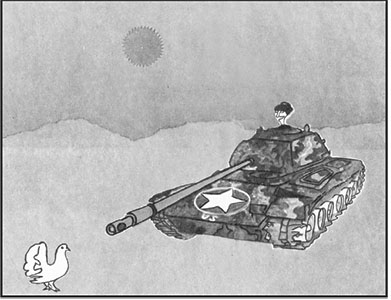

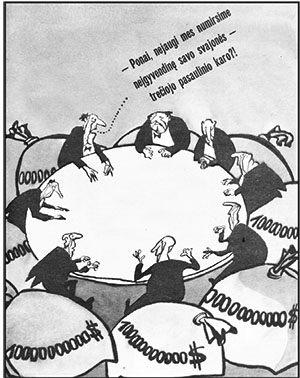

Nevertheless, artistic experiments with form and style persisted: Kęstutis Šiaulytis's long noses, Jonas Varnas's knots on cartoon frames, or an abstract drawing style subverted Soviet Realism. Writing "US" on a cartoon could mean "Union Soviet" rather than "United States" (Fig. 7). Despite the dollar signs on the money bags, the corpulent, sluggish bodies of the bureaucrats may have pointed to Brezhnev and his cronies rather than Western capitalists (Fig. 8).60

|

|

| Figure

7. By Kęstutis Šiaulytis, issue No. 7, 1982, 16. Courtesy Kęstutis Šiaulytis. |

Figure

8. "Gentlemen, don't

tell me we're going to die without fulfilling our

dream: World War III?" By

Kęstutis Šiaulytis,

issue No. 2, 1982, 16. |

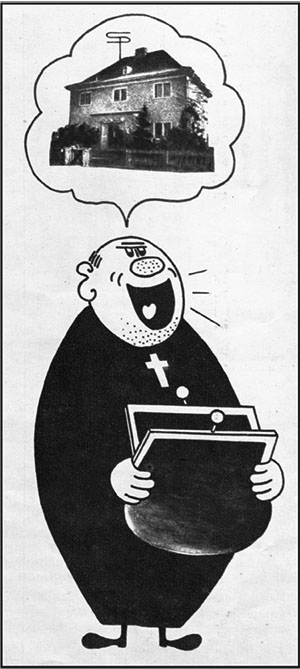

Fourth, silence was also a means to renegotiate Soviet official platforms. The recurrent complaining by Šluota's Communists about the lack of political cartoons illustrates a deliberate disengagement from Communist Party agendas. For example, there were very little antinationalist or antireligious critiques, despite Šluota's PPO requests and material incentives to promote such criticism.61 Šluota's Communist editors took a moderate position themselves and asked artists not to offend the religious beliefs of people, but to critique priests.62 A cartoon by A. Radvilavičius (Fig. 9), published in 1965, negatively portrays the priest, whose sluggish body and open purse show his greediness and undermine his religiosity.63

|

| Figure 9. "No comment," by A. Radvilavičius, issue No. 7, 1965, 8. |

And finally, coffee breaks and shots of vodka. Absenteeism, poor work ethics, and alcoholism were ridiculed in the pages of Šluota, but all were as much part of the work culture of Šluota's artists, journalists, and writers as they were for many other people. Their recollections were punctuated by phrases such as "We didn't show up in the mornings," "We went out for coffee," "We gathered in bars and restaurants to discuss everything," "We had a good time," "It was a wonderful time, full of celebrations," "We worked a little and then went out for drinks," and "Artists from other Soviet republics took a taxi to Vilnius to drink with us."64 Šluota's editorial PPO meetings routinely complain about the absenteeism, drinking, and lack of discipline of Šluota's artists, writers, and journal-ists.65 Alcohol and, much less so, coffee were a means to bridge the gap between "official" and "private," as well as to reshape the official moral universe of work ethics, moral purity, and discipline. Kęstutis Šiaulytis echoed others in his recollections about the editorial board: it consisted of wonderful people, and even Jonas Sadaunykas, the Executive Secretary, who pretended to be serious and used to tell others that he was a Stalinist to some extent, was actually a warm person who liked to drink. Laima Zurbienė recalled that her colleagues, when they got drunk, used to point at each other good-naturedly: "You're an informant." "No, you are, how else could you get a position at Šluota with your background?" Informants were present in every work collective, but, according to Zurbienė, nobody knew who informed for Šluota. It was a very good and beautiful collective, Zurbienė asserted, and the unknown informant contributed to its spirit by not reporting on the collective. Indeed, it is this personalized work culture that ultimately describes socialism in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, rather than the official codes of conduct anticipated in "The Moral Code of the Builder of Communism" or the goals of the Congresses of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It is this culture of togetherness, along with the journal's own social values and moral universe, that Šluota's artists, journalists, and writers long for today. This culture neither was, nor is perceived as "socialist" or "Soviet," relegating its most Soviet aspects, like Šluota's PPO meetings, to a footnote of history.

Another important question arises regarding how com-plicit Šluota's Communists were in artistic opposition and renegotiation of the official culture. Weren't they unable, for the almost twenty years for which archival data exist, to ensure that anti-imperialist and antireligious cartoons were part of every issue? Why would they tolerate drinking at work, and even drink together, at the same time they made Šluota a venue for the Soviet state's anti-alcoholism propaganda and argued for the importance of work discipline at most meetings? Or argue that the specificity of the journal didn't allow them to celebrate Lenin's anniversary or other great Soviet events as other journals did?66 Lenin, though, liked to laugh himself, as Albertas Lukša, the secretary of the PPO, stated at a meeting on November 24, 1969.67 Why did Šluota not run a story about Lenin's laughter?

In Lithuania in 1964-1985, Šluota's artists reproduced Soviet social and moral values, such as hard work and respect for the collective, but at the same time renegotiated official platforms through various means of opposition, such as hidden texts or silence about certain issues. Readers liked Šluota because humor engaged everyday issues that were relevant and made them laugh. Moreover, some were able to read between the lines and uncover hidden texts. They appreciated silence about some issues and were skillful in navigating Šluota and finding the most funny and admirable parts, such as Kindziulis's jokes, the cartoons, or foreign humor.68 Like Šluota's artists, readers participated in shaping and renegotiating Soviet values and ideologies. Their engagements were neither an example of clear collaboration, nor of open resistance, but rather a close interaction with power through dialogue, negotiation, acceptance, and rejection.

* * *

I

express deep gratitude to Kęstutis Šiaulytis for sharing his thoughts,

time, and work with me during my several years of research on Šluota.

Without his assistance and knowledge, I would not have been able to

complete this work. I am also very thankful to Vladimiras Beresniovas,

Andrius Cvirka, Andrius Deltuva, Goda Ferensienė, Šarūnas Jakštas,

Algirdas Radvilavičius, Jonas Varnas, and Laima Zurbienė for their

invaluable help. I am in debt to Kęstas Remeika, a vice director of the

Lithuanian Special Archives, as well as other LSA employees for their

supportive assistance. I am grateful to Daiva Litvinskaitė and one

anonymous reviewer for comments and suggestions.

Notes:

1 Open editorial party meeting, October

23, 1970, Lithuanian Special Archives (LSA), 1969-1971, fondas

(archive) 15020 (1), byla

(case) 9, p. 67.

2 Open editorial party meeting, April 19,

1973, LSA, f. 15020 (1), b. 10, p. 77.

3 LSA, 1972-1974, f. 15020 (1), b. 10,

pp. 29, 50.

4 At these meetings, Communist Party

members who worked at Šluota

assembled to discuss USSR and LSSR Communist Party Congress materials,

other important Communist Party documents, and Brezhnev's speeches, as

well as important Soviet anniversaries, such as the 100th anniversary

of Lenin's birth or the anniversary of Lithuania's incorporation into

the USSR. They also discussed how Šluota

meets USSR and Lithuanian Communist Party agendas, various issues

concerning the PPO, such as political education, work discipline, or

annual plans. Šluota's

PPO included the editor-in-chief (during the period of discussion it

was Juozas Bulota), the executive secretary (Jonas Sadaunykas was in

this position for many years), a PPO secretary and a deputy secretary,

as well as a few other editors, journalists, writers, or artists.

5 Parts of this article were published in

2011 and 2012 (see Klumbytė 2011, 2012).

6 On the artists' agendas, see Bulota,

"Šluotos kelias."

7 Bulota, "Šluotos kelias," 6.

8 According to the official publication records,

in 1971 there were 120,082 copies published. High numbers persisted

throughout the 1980s; in 1986, publication rates were still as high as

112,053. The numbers decreased in the early 1990s.

9 Specifically, I heard people quoting

jokes about Kindziulis, a popular joke cycle in Soviet times, but less

so in post-Soviet times. Kindziulis, a fictional cartoon character, is

a wise and funny man, an outside observer and a commentator.

Kindziulis's jokes usually end with a humorous short statement:

"Kindziulis joined us and said..." (Kindziulis priėjo ir tarė...). For

example:

"Why did you leave your job?" asks a neighbor.

"Because. because."

Kindziulis joined them and finished:

"Because he had to work." (Šluota,

July 31, 1986, 3)

10 Interviewees liked cartoons, short

satirical commentaries, foreign humor, jokes, and anecdotes. Some

readers preferred certain cartoonists over others. Satires and reports

on various social ills were not so popular.

11 Kauzonas interview with Jurgis

Gimberis. Šluota, albeit with short breaks, has been published in

post-Soviet times. The format was much smaller and the quality of

publication inferior to Soviet times. Šluota has been published online

since 2014; its editor-in-chief is Jonas Lenkutis.

12 Kauzonas interview with Jurgis Gimberis.

13

Šileika interview with Kazys Kęstutis Šiaulytis. Similar attitudes

about the decline of humor are expressed by other writers and artists

who contributed to Šluota in Soviet times. See Petronytė's interview

with Valdimaras Kalninis.

14 Collins, "Comedy and Liberty," 77.

15 See Freedman, "Wit as a Political

Weapon."

16 Oushakine, "Red Laughter," 204.

17 Freedman, "Wit as a Political Weapon."

18

From a speech during a meeting between the party and government and

literature and art specialists, March 8, 1963. Cited in "Šluota" karikatūros.

19 Bulota, "Juoko ginklu," 2.

20 See, for example LSA, f. 15020 (1), b.

9 and 10.

21 See also Klumbytė, "Soviet Ethical

Citizenship."

22 LSA, 1965, f. 15020 (1), b. 6, p. 1.

23 Ibid.

24 LSA, 1977, f. 15020 (1), b. 13, p. 46.

25

Ibid. These numbers do not include letters used by the literature

office, which received letters separately.

26 See, for example, LSA, 1975, f. 15020

(1), b. 11, p. 7.

27

There are also reports of letters with no value, focused on minor

issues, containing libelous remarks, etc. See, for example, LSA, 1977,

f. 15020 (1), b. 13, pp. 32-37.

28 C.f. Avižienis, "Learning to Curse in

Russian"; Oushakine, "The Terrifying Mimicry of Samizdat," 2001.

29 Personal communication, January 21,

2014.

30 LSA, 1969-1971, f. 15020 (1), b. 9, p.

5.

31 Ibid., pp. 5-7.

32 Personal communication with Kęstutis

Šiaulytis, Vilnius, summer, 2013.

33

See, e.g., LSA, 1972-1974, f. 15020 (1), b. 10, pp. 32, 52, 94, 96,

119; LSA, 1979, f. 15020 (1), b. 15, p. 12; LSA, 1969-1971, f. 15020

(1), b. 9, pp. 5, 34-35.

34 See, e.g., LSA, 1969-1971, f. 15020

(1), b. 9, pp. 8-9.

35

See ibid., pp. 35, 102, 115, 125; LSA, 1964, f. 15020 (1), b. 5, p. 2;

LSA, 1972-1974, f. 15020 (1), b. 10, pp. 85-86, 96-97.

36 LSA, 1972-1974, f. 15020 (1), b. 10,

pp. 48, 59; LSA, 1978, f. 15020 (1), b. 14, pp. 13-14.

37 LSA, 1979, f. 15020 (1), b. 15, p. 12.

38

LSA, 1975, f. 15020 (l), b. 11, pp. 29; LSA, 1972-1974, f. 15020 (1),

b. 10, pp. 30, 52, 117-119, 130; LSA, 1978, f. 15020 (1), b. 14, pp.

36-37. Pakalnis joined the CP in the 1980s.

39 LSA, 1979, f. 15020 (1), b. 15, p. 12.

40 LSA, 1969-1971, f. 15020 (1), b. 9, p.

35.

41 For example, in 1977, the fourteen

most active artists who contributed to Šluota

participated in the international exhibit "Satire in the Fight for

Peace" in Moscow. Two artists received prizes, while Šluota received a

certificate of honor from the Soviet Peace Defense Committee. LSA,

1977, f. 15020 (1), b. 13, p. 25. According to Kęstutis Šiaulytis, Šluota's successes

continued in the 1980s. (Personal communication in Vilnius, summer,

2013.)

42 LSA, 1972-1974, f. 15020 (1), b. 10,

pp. 117-118.

43

The publication of comic strips, which were considered a capitalist

genre, was discontinued and later revived. Comic strips were a modern

artistic form liked by the readers, and Šluota's Communists

themselves encouraged the revival of comic strips. J. Sadaunykas argued

in 1974 that Šluota

lost many readers when Palčiauskas's comic strips were discontinued.

LSA, 1972-1974, f. 15020 (1), b. 10, p. 118.

44 Berdahl, Where the World Ended,

198-199.

45 Feldman, "New Thinking about the 'New

Man,'" 153.

46

See XXII S''ezd KPSS, 3:317-318. In 1961, the Twenty-second Congress of

the Communist Party of the Soviet Union issued the landmark "Moral Code

of the Builder of Communism." The 1961 code consisted of twelve tenets,

eleven of which addressed human relations: devotion to the Communist

cause, love toward the Socialist Motherland and to Socialist countries,

friendship and respect for other socialist societies and among the

peoples of the USSR, hard work, collectivism, humane relations and

mutual respect between people, honesty, truthfulness, moral purity,

simplicity, and modesty in social and personal life, mutual respect

within the family and concern for the upbringing of children.

47 See the work related themes listed in

the May 26, 1978 report. LSA, 1978, f. 15020 (1), b. 14, pp. 15-17.

48 Rimantas Baldišius cartoon, Šluota, No. 5,

1985, 2.

49 "... Pačių skęstančiųjų reikalas"

[.responsibility of the drowning]. Šluota,

No. 5, 1980, 11.

50 Field, Private Life and Communist Morality, 13, 16; see

also Irreconcilable Differences.

51

In general, men were lampooned in Šluota far more than female

characters. Directors, bureaucrats, fishermen, alcoholics, and assorted

clerks, lovers, and cheaters are uniformly men.

52 Šluotos

kalendorius, 1971, 19.

53 A cartoon by Andrius Deltuva. Šluota, No. 18,

1967, 10.

54 Šluota,

No. 1, 1966, 5.

55 LSA, 1969-1971, f. 15020 (1), b. 9, pp. 69-70.

56

In Soviet Lithuania, Aesopian language was a special type of cryptic or

allegorical writing used in literature, criticism, and journalism to

circumvent censorship, since direct writing was denied freedom of

expression. I use this term to speak about the artistic language of

cartoons since they had texts hidden behind what was evident.

57

Goda Ferensienė worked in the literary division of Šluota and left the

journal in the 1960s. Laima Zurbienė was hired in the 1970s and, like

others cited in this article, worked at Šluota until the 1990s.

58 Klumbytė, "Soviet Ethical Citizenship.

59 LSA, 1969-1971, f. 15020 (1), b. 9,

pp. 6-7.

60 I thank Kęstutis Šiaulytis for these

points.

61 LSA, 19721974, f. 15020 (1), b. 10, pp. 85, 107.

62 LSA, 1978, f. 15020 (1), b. 14, p. 6. See also LSA,

19721974, f. 15020 (1), b. 10, pp. 105107.

63 Šluota,

No. 7, 1965, 8.

64

The note about taking a taxi to Vilnius most likely refers

to

the 1960s, since, according to Kęstutis Šiaulytis, because of later

editorial board changes in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, these

gatherings were discontinued, even though close relationships continued

between some people.

65 Lithuanian Communist Party archives, f. 15020 (1), b. 1,

3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10.

66 For example, see LSA, 1969-1971, f.

15020 (1), b. 9, p. 26.

67 LSA, 1969-1971, f. 15020 (1), b. 9, p.

33.

68 On Kindziulis, see footnote 9.

WORKS CITED

Avižienis, Jūra. "Learning to Curse in Russian: Mimicry in Siberian Exile," in: Baltic Postcolonialism. Edited by Violeta Kelertas. Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi, 2006.

Berdahl, Daphne. Where the World Ended: Re-Unification and Identity in the German Borderland. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

Bulota, Jonas. "Šluotos kelias," in: Šluota. Edited by Jonas Bulota and Arvydas Pakalnis. Vilnius: Mintis, 1984.

______. "Juoko ginklu," in: "Šluota" karikatūros. Vilnius: LKP CK Laikraščių ir žurnalų leidykla, 1964.

Collins, Ronald K. L. "Comedy and Liberty: the Life and Legacy of Lenny Bruce," Social Research, 79 (1): 61-86, 2012.

Feldman,

Jan. "New Thinking about the 'New Man': Developments in Soviet Moral

Theory," Studies in Soviet Thought, 38 (2): 147-63, 1989.

Freedman, Leonard. "Wit as a Political Weapon: Satirists and Censors," Social Research 79 (1): 87-112, 2012.

Field, Deborah A. Private Life and Communist Morality in Khrushchev's Russia. New York: Peter Lang, 2007.

Field, Deborah A. "Irreconcilable Differences: Divorce and Conceptions of Private Life in the Khrushchev Era," Russian Review 57 (4): 599-613, 1998.

Kauzonas,

Ferdinandas. Interview with Jurgis Gimberis. "How I and J. Gimberis

Failed," Respublika, April 3, 2008. Accessed March 20, 2009 at http://www.kamane.lt/lt/atgarsiai/literatura/litatgar-sis231.

Klumbytė, Neringa. "Soviet Ethical Citizenship: Morality, the State, and Laughter in Lithuania." In: Soviet Society in the Era of Late Socialism, 1964-85. Edited by Neringa Klumbytė and Gulnaz Sharafutdinova. New York: Lexington Books, 2012.

______. "Political Intimacy: Power, Laughter, and Coexistence in Late Soviet Lithuania," East European Politics and Societies 25 (4): 65877, 2011.

LSA (Lithuanian Special Archives). The editorial Šluota's office Communist Primary Party Organization documents. Party meeting notes and reports. Cases 1, 3-8, 10-15, 1960-1979.

Oushakine, Serguei A. "'Red Laughter': On Refined Weapons of Soviet Jesters," Social Research 79 (1): 189-216, 2012.

______. "The Terrifying Mimicry of Samizdat," Public Culture 13 (2): 191-214, 2001.

Petronytė,

Jurga. Interview with Valdimaras Kalninis, "Linksmajai dailei-podukros

dalia" [Humorous art is the stepdaughter of art]. Accessed December 22,

2009 at

http://www.ve.lt/?rub=1065924826&data=2006-03-31&id=1143728862.

Šileika,

Ričardas. Interview with Kazys Kęstutis Šiaulytis, "Negalime būti tik

praeiviai nereaguojantys į tai, ką mato" [We can't just be passersby

who do not respond to what they see]. Literatūra ir menas, August 22, 2003.

"Šluota" karikatūros, 1934-1964 m. Vilnius: LKP CK Laikraščių ir žurnalų leidykla, 1964.

Šluotos kalendorius. Vilnius: Mintis, 1976.

Šluotos kalendorius. Vilnius: Mintis, 1971.