Copyright © 2014 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Editor of this issue: Vida Savoniakaitė

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2014 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume

60, No.4 - Winter 2014

Editor of this issue: Vida Savoniakaitė |

Contemporary Social Art Festivals as Intertextual Manifestations of Postmodern Cultural Identity

VYTAUTAS TUMĖNAS

VYTAUTAS TUMĖNAS is a research fellow in the Department of Ethnology at the Lithuanian Institute of History. He is the author of Lietuvių tradicinių rinktinių juostų ornamentas: tipologija ir semantika. Lietuvos etnologija 9 and numerous studies and articles on ethnology and the study of art in folk ornament symbolism.

Abstract

The search for cultural identity based on specific mythopoetical

images and symbols can be treated as a manifestation of the

aesthetic ideas of antimodernization, archaization, and folklorism.

The author seeks to define the mythopoetical, textual, and

codic aspects of the Lithuanian ornamental tradition and to reveal

its intertextual vitality in modern culture, unfold the contextual

links of these images within a broader Lithuanian and

cross-cultural context, and demonstrate creative interpretations

of traditional ornamental forms and symbolism in contemporary

social art performances in Vilnius. The author concludes

that modern symbols links with the mythic tradition suggest

a new significance, not only of national identity, but even more

so as the expression of cultural identity based on mythological,

interdisciplinary, and intertextual language associated with the

paradigms of collectiveness, archaism, and traditionalism.

Traditional folk culture symbols are in the process of revival

in todays Lithuanian culture. Folklore and folk art inspire

forms of contemporary art practices that seek a cultural identity

based on a meaningful heritage. The artists are actively exploiting,

quoting, transforming, interpreting, and adapting the

texts, forms, and meanings of archaic tradition in new contexts

and circumstances. Folk culture from the countryside is invited

to participate in the festive life of modern cities.

Though the aesthetic ideology of folklorism, as a broader notion of historicism, as secondary folk culture, which is in contrast to natural, genuine, old folk culture,1 or the conscious recognition and use of folklore as a symbol of ethnic, regional, or national identity,2 determines this modern way of folk life;3 a similar strategy can be recognized in contemporary transformations of visual folk art. The intertextual nature of the creativity of creators, artists, or interpreters becomes a significant feature of this phenomenon. Explaining intertextuality, Julija Kristeva commented that every text and every reading depends on prior codes. A literary work, then, is not simply the product of a single author; any text is constructed of a mosaic of quotations and every text is the absorption and transformation of another.4 Similarly, Roland Barthes, in The Death of the Author, explained that every text is a new tissue of past citations: Bits of code, formulae, rhythmic models, fragments of social languages, etc. pass into the text, for there is always language before and around the text. Gerard Genette proposed the term "transtextuality," which distinguished several subtypes of in-tertextuality (quotation, plagiarism, allusion) and paratextual-ity" (the relationship between a text and the paratext that surrounds the body of the text, such as titles, headings, prefaces, dedications, acknowledgements, footnotes, illustrations, etc.).5

Several scholars have carefully investigated the vitality of mythopoetical symbols of the archaic world outlook in contemporary Lithuanian literature and music,6 although creative interpretations of the Baltic mythological tradition, linked with sacred geometry or traditional ornament, are not widespread in modern professional Lithuanian culture. A unique phenomenon of this artistic thinking, connected to or influenced by the science of mythology and cultural anthropology, is the well-known oratorio composed by Bronius Kutavičius, Paskutinės pagonių apeigos (The Last Pagan Rituals) with its ornamentally written score.7 Scholarly and creative interpretations of ornamental tradition in neighboring Latvia's modern culture are described by Valdis Celms,8 However, modern interpretations of traditional symbols in contemporary Lithuanian culture remain in short supply.

There are archaic symbols in many cultures, traces from an entirely different cognitive pattern based on a mythopoetical model, like the case of the Latin American Quechua culture, which uses poetic images integrated into mythical thinking instead of rational logic.9 The increasingly specific scholarly investigations into archaic pattern symbolism are simultaneously changing many contemporary artists' attitudes toward folk ornament. Traditional patterns obtain a revitalized intellectual cognition and meaning linked with a mythological and mystical approach to the universe. Artists actualize traditional textile symbols in various exterior design projects and narrative comments, in the patterns of pyrotechnics, in stadium dance performances, etc. Although the symbolism of ancient ornaments is interpreted in terms of modern culture, at the same time, it can be qualified as a living tradition due to its associations with a mythological world view.

The Intertextuality of Archaic Symbols:

The Complex Referential Links of the Forms and Folk Names of Ornaments

According to the Estonian semiotician Juri Lotman, every culture needs key symbols of an archaic nature derived from the era when the elementary signs had the function of accommodating broad and significant texts stored in the collective oral memory. The symbol does not belong to one particular synchronic layer of culture; it comes and goes from the past to the future. It emerges as a messenger of other eras, as a reminder of ancient and eternal cultural foundations. Implementing the cultural memory of oneself, these symbols unite culture, preventing it from falling into chronologically isolated layers. The integrity of the major symbols and the longevity of their cultural life largely determine the boundaries of national and area cultures.10

In my view, the patterns' archaic symbolism may be revealed and revived based on their folk names connected with mythopoetical images of narrative tradition and on a semiotic comparison of the patterns' compositional schemes, as well as on a wider contextual, intercultural analysis. Some of these names refer to mythopoetical images of folklore and are widespread in the Lithuanian tradition, as well as in those of Latvia, Belorussia, Russia, etc. The names of these patterns promote wide implications for an understanding of ornament as a part of the mythological tradition that inspires modern artistic ideas. Research reveals significant features of a traditional mentality and of the existence of the associative and contextual interconnections of visual signs, their mythopoetical images, elements of the biosphere and atmosphere, and attributes of mythic beings.

Traditional Baltic woven sashes were usually patterned with two, three, or four different ornamental motives. Another distinctive characteristic of the sash is its geometric composition of ornaments, using huge numbers of different patterns linearly composed in changeable sequence. These sashes were only popular in some regions of Latvia (Lielvarde, Krustpils, Rucava, and others in Kurland), Lithuania Minor (Klaipėda, Šilutė, Tilžė), and Lithuania (Palanga, Ukmergė, Pakruojis, Pasvalys). This type of ornamentation presupposes the presence of linear reading in the Baltic cultural tradition.11 It is similar to the linear reading of runic script known in medieval Lithuania.

The oldest formal examples of East European geometrical ornamentation can be traced from the protoscript, symbols, and ornamentation of the Neolithic Old Europe Civilization.12 An elaborated tradition of the same geometrical patterns arranged in a multipatterned irregular order is well known in Latvia13 and Finland14 at the beginning of the second millennium.

I have distinguished twenty-five traditionally-named pattern types of Lithuanian sash ornament, based on their traditional complex unity in form and name.

The referential links of visual symbols and patterns of folk art as signifiers, with their folk names or mythopoethic images as signifieds related to the discourses of folklore and mythology of the Slavic, Finno-Ugric, and Baltic oral tradition, have been analyzed from an interdisciplinary point of view.15

Earlier, the Latvian scholars Edvards Brastinš 16 and Jekabs Bine 17 contextually compared and linked the folk names of national patterns with symbols in archaeological decorations. They associated these names, as mythopoetical images, with deities and their attributes in Latvian folklore and mythology.

That the same folk names sometimes refer to different patterns suggests the similarity of their symbolism. In addition, the same pattern may have several different names. These peculiarities represent the variability in associations of the different pattern forms and names, which reflects the sophisticated links of the various mythopoetical images and suggests another method for systematic analysis of the mythological worldview, based on attempts to understand the meaning and logic of archaic associative thinking. For example, the net of associations between the mythopoetical images of an apple, star, wolf, swan, duck, bride, or heart may be revealed by analyzing the logic and meaning of the intercodic associations of the Toothed Diamond sign in Lithuanian folk culture.

The Toothed Diamond sign has the names žvaigždė (star)18 and obuoliukas (apple).19 An apple in Lithuanian folklore is often associated with fertility, matchmaking, and marriage.20 In Indo-European mythologies, golden apples are linked with eternal youth and immortality.21

The same sign in Lithuanian folk

textile has a significant name vilko

gerklė (wolf's mouth).22 This name corresponds with

calling a woman a wolf when she first enters the bathhouse after

childbirth.23

The wolf appears in fertility magic: if you want your bees to steal the

honey from other bees, you must let the beehive fly through the open

mouth of the wolf.24

In traditional Lithuanian dream symbolism, wolves signify matchmakers

and bridegrooms.25

The wolf's mouth symbol is probably similar to the vagina dentate

image, well-known in the Medieval European tradition. A drawing in a

fourteenth-century book from Vienna of "The Seven Deadly Sins"

represents a crowned woman-fish. She has a wolf's head with an open

mouth depicted in place of the woman's genitals.26

Basing his conclusion on the traditions of various cultures all over

the world, Mircea Eliade asserts that the vagina dentate

often represents the mouth of chthonic Mother Earth in initiation

ceremonies associated with symbolic death - a return to the womb and

rebirth in a superior state.27

Another name for the Toothed Diamond is žųsiąžarnis (goose

intestine)28

that, like the neighboring Belarusian denomination, "swan,"29

suggests an association with waterbirds. A goose, a duck, a swan, and

other waterbirds are bridal and marriage symbols in Lithuanian

folklore. In songs of courtship and matchmaking, a young girl is

associated with a waterbird:

The duck is clearly the symbol of matchmaking in another type of song, where the girl lacks the courage to come closer to the boy because she is afraid she will be late returning home and provoke her mother's angry questions about where she has been. The boy suggests she answer that a flock of geese landed in the lake and muddied its waters. The boy has seduced the young girl, and the mud has not yet disappeared.31

Traditional Patterns in Contemporary Festivals

Archaic symbol, according to Juri Lotman, retains its semantic and structural independence in any context: it is a text of defined boundaries that allow it to be clearly distinguished from the surrounding semiotic context and easily incorporated into a new environment. On other hand, the semantic potency of a symbol is always wider than its given implementation. It forms a semantic reserve with which a symbol can initiate unexpected connections, changing its substance and deforming the textual environment in an unforeseen way.32

Some contemporary artists are interested in the actualization of traditional Lithuanian ornament symbols. An important original implementation of traditional ornament geometry into the figures of stadium dance choreography was created for the Dance Day of the traditional Lithuanian Song Festival (2009) with a scenario by Birutė Marcinkevičiute and chief ballet-master Laimutė Kisielienė.

The First Fire-Sash Project

The interpretations of traditional patterns became an important element of popular cultural events in Vilnius: The Fire-Signs of the Autumn Equinox joined with an older event, The Fire-Sculpture Festival of the Autumn Equinox (both coordinated by Eglė Plioplienė). This cultural action, which used interpretations of traditional textile symbols, attracted crowds of people. The projects' participants included professional artists, as well as amateurs, beginners, students, and school children, and founded a new artistic tradition associated with mythological and traditional aspects of contemporary culture. The ornamental fire performance started in 2005 during the annual Autumn Equinox Festival (around 21-24th of September) on the right bank of the Neris River near Cathedral Square and King Mindaugas Bridge. The author Julija Ikamaitė and the author of this article connected the candlelight ornamentation with the sacredness of the Šventaragis Valley, where in ancient times an eternal fire smoldered in a temple. Lithuanian dukes had been cremated on that spot. The artists sought to evoke the greatness and power of fire, its creative and destructive aspects, and the temporary forms of the eternal life-force. About fifteen hundred candles were installed on the architectonic diagonal-squared Neris River bank construction with the help of 140 pupils and their teachers from ten Vilnius schools. The huge 300-meter-long installation of candles was easily observed by crowds of people from the bridge and the opposite side of the river (Fig.1).

|

|

Fig. 1

The ornamental multipatterned sash of flaming candles at the

Autumn Equinox Festival in Vilnius, September 24, 2005. Photo

by the author.

|

The concept and planning for this fire sash's performance location and its form was generated over a year. The creators were stimulated by antimodern aspirations to continue the old Baltic tradition of multipatterned woven sash ornamentation. The researchers presumed the ornaments may be associated with mythological tales, cosmological legends, or prayers. It was decided to compose the candle flames in a similar multipatterned and changeable order. with mythological tales, cosmological legends, or prayers. It was decided to compose the candle flames in a similar multipatterned and changeable order.

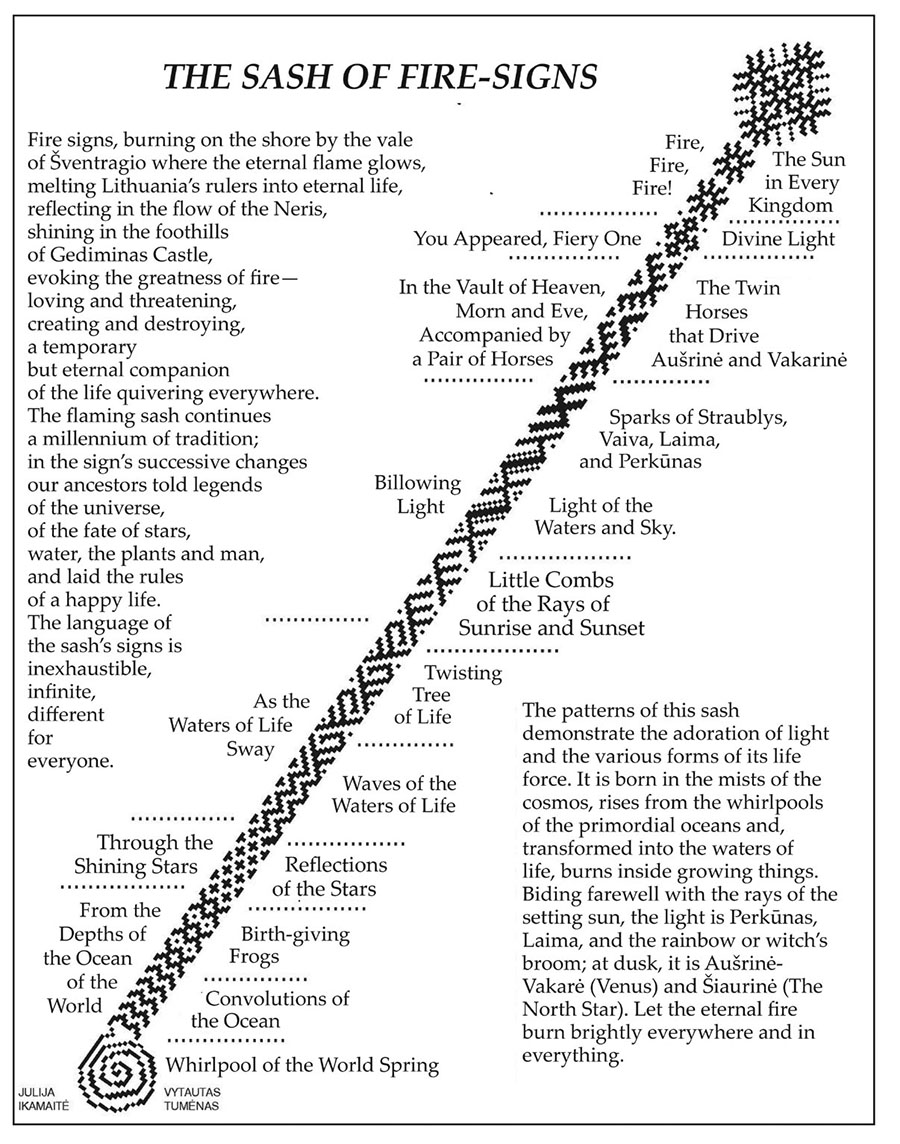

The Sash of Fire-Signs was organized for reading from left to right. The authors aimed to describe the specific meanings for the different parts of this ornamentation expressed by their names and the explanations given for them based on folk tradition (Fig. 2).

. |

| Fig. 2 The Sash of Fire-Signs and

explanations of the patterns meanings by Julija Ikamaitė (left side) and Vytautas Tumėnas (right side). The Autumn Equinox Festival in Vilnius, September 24, 2005. |

In the textual comments on the lower right side, I have explained the message of the Sash of Fire-Signs, which includes references to Perkūnas, the Lithuanian God of Thunder, and his wife Aušra, associated with sun rays, beauty, and youth. Perkūnas had transformed his wife into Laumė, Lauma or Mara, because of her misconduct, and punished her by sending her to live on Earth.33 Laumė is associated with female sexuality. This divine pair is similar to another pair, the Sky Light God, Dievs, and his wife, Mara, in the Latvian tradition, and Laima, the deity of marriage, happiness, and fate in the Baltic tradition. Laima is similar to the Sun Goddess in Latvian tradi-tion.34 The ornamental sash also referred to the rainbow named vaivorykštė or Laumės juosta (The Sash of Laumė). J. Ikamaitė expressed the symbolism of the Fire Sash in poetry on the left side of the Fire-Sash illustration (Fig. 2).

I have ascribed the patterns with mythopoetical images or names. Reading from bottom to top on the right side of the sash, the ornaments' names are Spiral, (labeled Whirlpool of the World Spring in the diagram); Vertical Zigzag, (Convolutions of the Ocean); Frog (Birth-giving Frogs); Small Crosses (Reflection of the Stars); Zigzag (Waves of the Waters of Life), Hooked Horns (Twisting Tree of Life); Combs (Little Combs of the Rays of Sunrise and Sunset); Broken Half-Cross (Sparks of Straublys,Vaiva, Laima, and Perkūnas and Light of the Waters and Sky); Two Horses (The Twin Horses that Drive Aušrinė and Vakarinė); Candelabra (Divine Light); and Candelabra/Rose (The Sun in Every Kingdom).

What is the symbolism of these patterns from a scholarly viewpoint?

The whirlpool image in Lithuanian folklore is associated with the mythology of birth and with the mythic beings of the Aušra (similar to Greek Aphrodite) group, associated with marriage symbolism. The Spiral sign, the female symbol associated with the idea of fertility and creation, was well-known in Old European culture, where it was depicted on the bellies of female deities.35

The Middle of the Ocean in Lithuanian folklore is associated with the source of life, where the palm tree, the Tree of the World, grows.

The Frog image (See Fig. 5F) is associated with birth and rebirth, transformation, and reincarnation in the traditional Lithuanian world outlook.

The Zigzag is the symbol of life-giving water, a symbol widespread in world mythology. And twisting, according to tradition, is associated with the growing Life Tree. A Toothed Zigzag is called the žųsiąžarnikė (goose intestine) and linked with the symbolism of waterbirds.

The Comb image in Lithuanian folklore is associated with a young girl drifting along in a boat as she combs her hair. Mythologically, the comb has been explained as an attribute of the Morning Star, and hair combing is an activity of Aušrinė, who is considered an analogue to Venus or Aphrodite. In folk tradition, the Rake sign is called grėbliukai36 (rake or raker) or šukos37 (comb) and sometimes vėželis (crab) and vėžlelis (turtle). In Lithuanian Užgavėnės (Mardi Gras) folk songs, a girl in a boat in the middle of a sea, a lake, or river combs her hair with a fish-bone comb, then floats downriver to her beloved to ask him if he loves her. But the boy answers that he does not and is willing to make a rake from her fingers.38 It is evident that the images of the rake and comb are associated with the idea (or problems) of courtship and matchmaking. The image of a girl sitting in a floating boat while combing her hair is also used in a folksong sung during hair-combing rites on the eve of a wedding. In these songs, an orphan girl is mourning the absence of all her family members. Mercifully, Father Moon, Mother Sun, Brother Pleiades, and Sister Star substitute for them during the wedding.39 Who is this girl, with the Moon for a father, the Pleiades her brother, and the stars her sisters? Perhaps she is the deity of the Morning Star; for this context is similar to the mythological images of the solar or morning-star goddesses of the Indo-European tradition (for example, Greek Aphrodite, Hindu Ushas): her hair is a metaphor for the rays of the Sun, the planet Venus (Aušrinė), or the morning sunrise.

Other evidence linking the Rake pattern with the Comb is that it has the same name, гребешок (comb),40 in the Arkhangelsk region of northern Russia. It is important to note that the comb is a significant artifact of success in matchmaking in Ukrainian41 and Lithuanian wedding rituals.

It is also significant that the Rake pattern on the bridal shirt in Udmurtia (a Finno-Ugric area of Russia) has the name "Duck Wings."42 This links the image of a rake with the image of a duck, because both images have wedding symbolism.

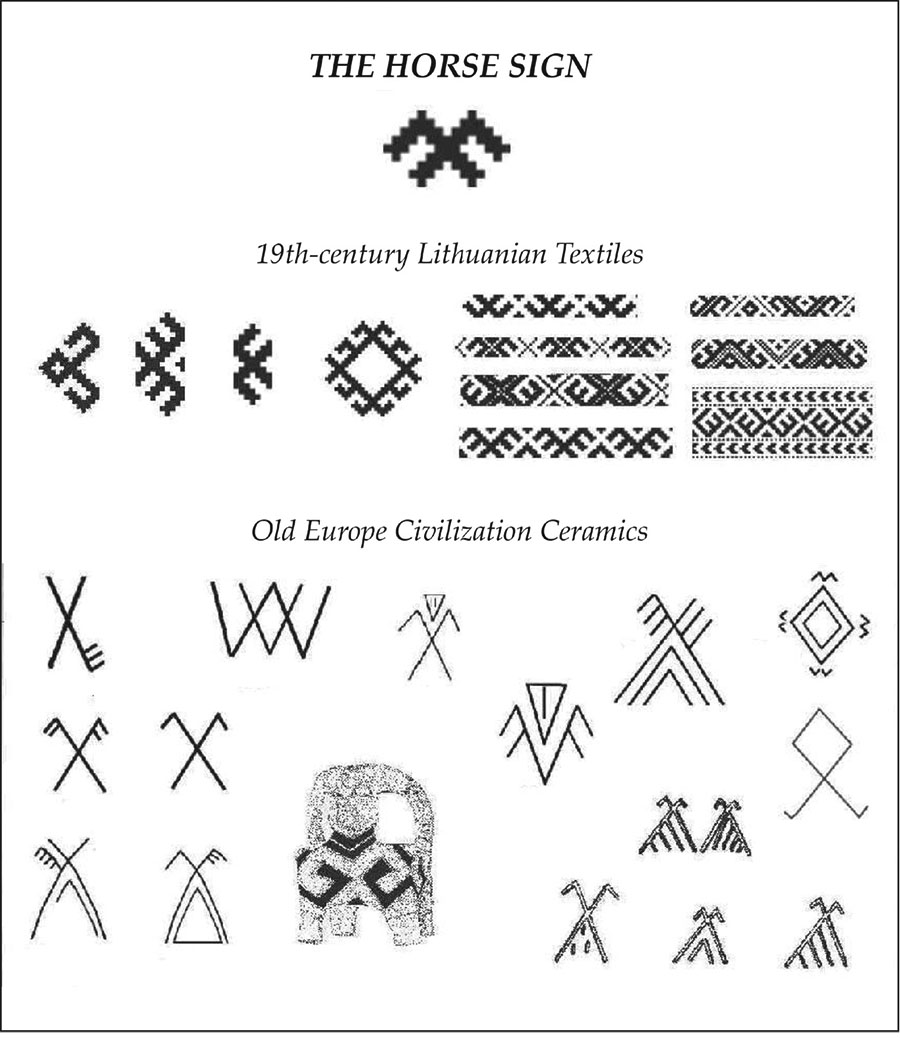

The Swastika and other signs derived from it (Fig. 5B) are associated with the luminaries of the sky, especially with the sun and its light, in many traditions.43 In Indo-European mythology, the Aušrine-type deity is conducted across the sky by the Divine Twins (Greek Dioskouros; Hindu Ashwinau, Ashwini Kumaras; Lithuanian Dievo sūneliai; Latvian Dieva deli, Jumis) riding horses. The Horse pattern and its variations (Fig. 3; Fig. 5E) are widespread in Lithuanian textile tradition. It was very popular in the Old Europe Civilization (for example, the ram-like oil lamp decorated with a horse sign in Fig. 3). The Horse-type sign is related to the mythology of the Twins,44 and possibly symbolized the mediator who carries light and fire between worlds (Fig. 3). The Divine Twins are mentioned in Lithuanian folk meteorology as well: the two light columns flanking the sun on both sides at sunrise or sunset ("sundogs" in English) as a prognostic sign of cold weather are named saulabroliai (brothers of the sun).

|

| Fig. 3. The Horses sign in Lithuanian

textiles compared to Old Europe Civilization ceramic signs. |

According to tradition, the Rosette (Fig. 5D) can symbolize the sun and celestial light.

The Second Fire-Sash Project

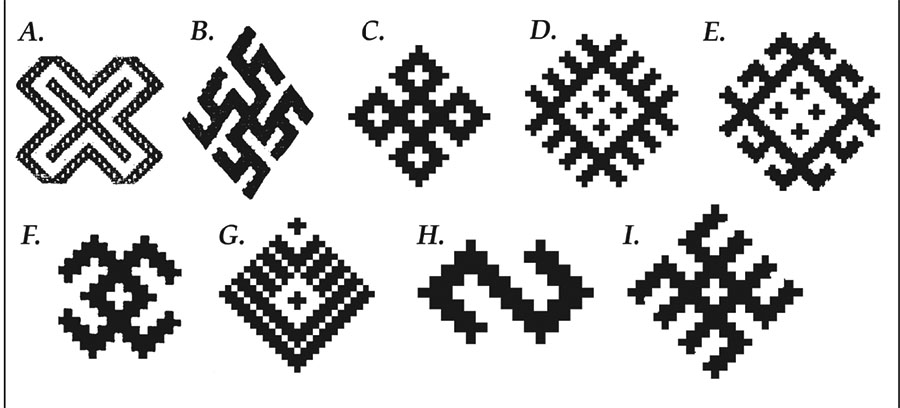

A similar project was created in 2008 and realized on September 21 in the same place on the same occasion. The symbolism of these signs, based on scholarly investigation, was briefly described in a booklet distributed to the public during the festival. But the concept of this performance was simpler than 2009 project. In this project, the narrative aspects of the ornaments (similar to a poem or a story) were not developed (Fig. 4).

|

| Fig. 4. Fire ornaments by Julija Ikamaitė,

Mindaugas Aliukas, and Vytautas Tumėnas at the Autumn Equinox Festival in Vilnius, September 21, 2008. Photo

by the author.

|

|

| Fig. 5. The schemes of the nine patterns

installed on the bank of the Neris River during the Autumn Equinox

Festival in Vilnius, September 21, 2008. |

Nine fire patterns were installed at this festival: A.) the Cross, in Lithuanian folk nomenclature known as the sign of beginnings, initiation, and protection, or krikštelis (baptism sign) or gvazdikėlis (dianthus); B.) the Broken Cross, Swastika (sulaužtinis kryžiukas), in Latvian culture known as Perkona krusts or Laimas krusts (the cross of Perkons or Laima); C.) the Five-squared Cross, traditionally called liktoriukai (lamp or candelabra); D.) the Horse sign, called žirgeliai (horses) or arklio galvukė (horse's head); E.) the Rosette or Horned Square joined with the Rhombus sign, with four dots in the middle of the crossed square: the first element is called roželė (rose) or erškėtėlis (wild rose), snaigė (snowflake), būrtukė su grėbliukais (magic wooden tablet with rakes), or žvaigždutė (star); the second element is called akutės (eyes) or varnakis (crow's eye), būrtukė (magic or squared wooden tablet), riešutukas (nut), langučiai (windows) or kryžlangėlis (cross window). F.) This sign is named varlytė (frog), vėžlelis (turtle), vėželis (crab, cancer), voras (spider), or plačiakojis (straddled legs); G.) the Herring Bone sign, traditionally known as eglutė (pine tree) or šluotelė (whisk broom); H.) The Serpent sign is called žaltinėlis (grass snake) or zuikutis (hare); I.) The Bee sign's traditional name is unknown.

In the Lithuanian narrative tradition, the Horned Rhombus or Rose (Fig. 5D) is a star-like sign, which has the name žvaigždutė (star),45 but also gėlytė (flower),46 roželė (rose),47 and snaigė (snowflake).48 This sign is placed at the top or center of cosmic structure compositions in nineteenth-century East Prussian carpets called koc.49 The context of Baltic folklore and mythology demonstrates the strong association of the Rose sign with sun or star symbolism, with the images of the flowers of the World Tree, Sun Garden, or Sun Bush at the Center of the World or Sky, and with the highest level in the cosmo-logical structure. In Latvian songs, the rising and setting sun is depicted as a rose wreath, bush, or garden. A rose garden is one of the most characteristic motifs in Baltic mythology. The association between the Sun as celestial fire and the image of a rose is known in Lithuanian and Latvian mythological folklore.50 The Horned Rhombus represents the sun, and sometimes it is called this: in Lithuanian, saulukė,51 and in Latvian, saulyte.52 In Lithuanian folklore, the sun rising on Christmas morning is associated with, or replaced by, the flowering rose and has marriage symbolism:

On Christmas morning the rose

bloomed

The deer with the nine

horns is coming

On one horn the fire

burns

On the second - the

smiths are hammering

Oh smiths, my brothers

Please make me a golden

ring.53

This song brings to mind the image of the sun forged by a smith (kalvelis/televelis, a name similar to the Estonian mythic hero Kalev) who is similar to the servant of the Thunder God, Perkūnas, in Lithuanian mythology.54 Another association of the Rose image, with a star or the sun, as well as fertility, is evident in the names of the flax laid out for drying in the sun during harvest rituals. The figure so formed - the circle of rays - was called rose, star, wreath, or circle.55 The other pattern name, Star, also refers to the sky luminaries, and its synonymous name, Snowflake, designates snowflakes as sky elements, given their similarity to falling stars. Another rarely used name for this sign, katės pėdukė (cat's paw),56 again harks back to the love and marriage symbolism of the sky luminaries in Lithuanian folklore.

Sometimes the rožytė (rose)57 or žvaigždukė (star)58 bears the Chessboard pattern. But it is better known as katpėdėlė (cat's paw).59 The Chessboard pattern consists of a combination of five dark squares and four light ones. A Cat's Paw resembles a feline paw-print, but is also like a flower with four petals with a spot in the middle. In the Lithuanian folkloric tradition, cats are symbolically associated with female sexuality. That is why it is best to sow rue (a most important virgin apotropaic symbol in Lithuanian tradition) on St. George's Day and to harrow it with a cat's tail or leg. By examining the wedding symbolism of the cat, we can explain the connection between the Cat's Paw pattern and the Rose and Star images.

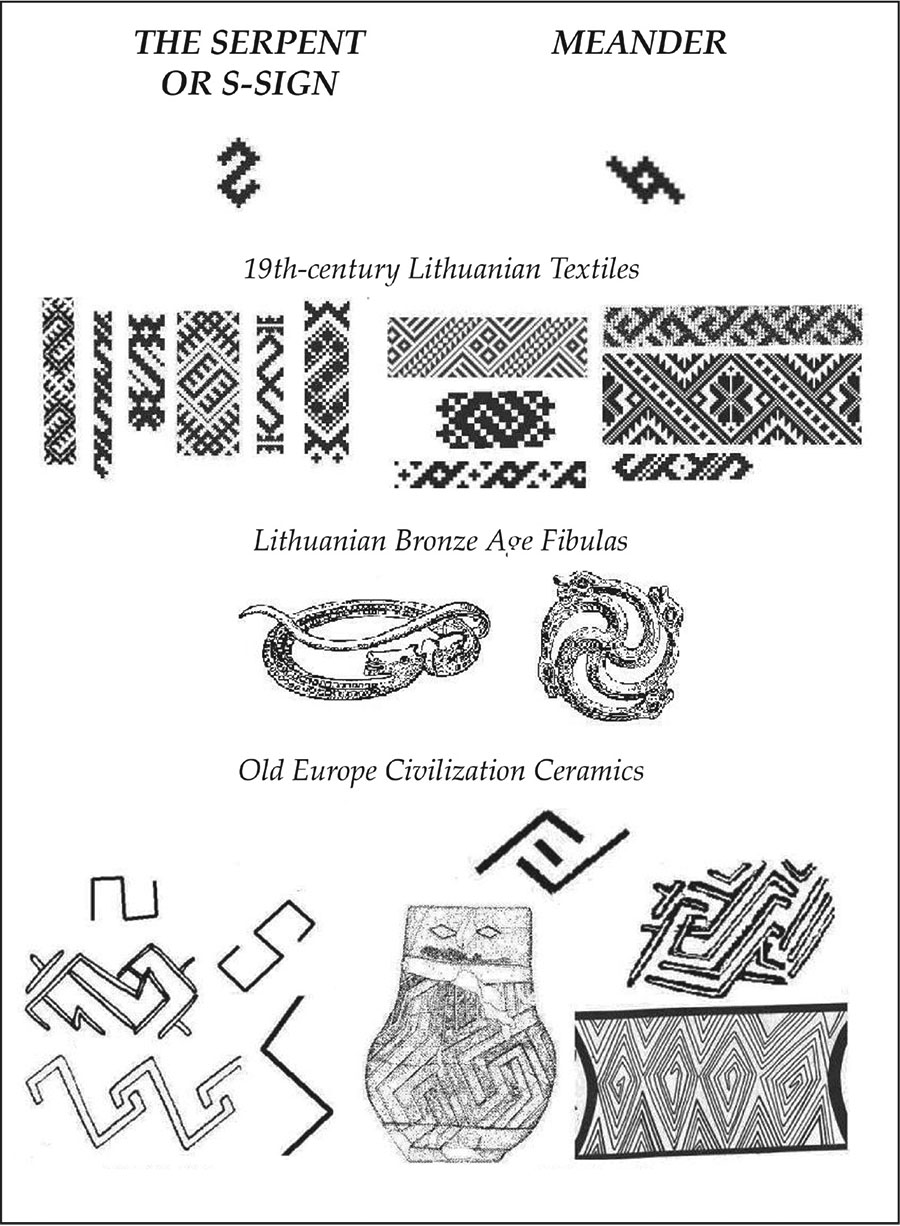

The Serpent sign (Fig. 5H), known as žaltinėlis in Lithuanian,60 is popular not only in Lithuanian sash decoration, but also in wooden architecture, folk furniture painting, other interior decoration, and even on Easter eggs. It was popular in archaeological jewelry. The earliest examples of this sign can be found in Old European ceramics, where it can be interpreted as the symbol of the dynamism of the life force (Fig. 6). In the well-known Lithuanian folk tale Eglė, the Queen of the Serpents,61 a wedding agreement is made by a young girl after bathing in the sea when the king of the underwater world, the King of Serpents, will not return her clothes unless she agrees to marry him. In earlier times, grass snakes were almost domestic animals - they lived inside homes, and there was a belief that if a grass snake leaves the house, it means someone in the home will die.62 The Serpent image may stand for a vital power, the life force, love and family, and fertility, and is strongly connected with women.63 The Serpent sign, also known as the S sign, arranged as two serpents or dragons and spirals, was one of the most popular signs in Tripolye-Cucuteni ceramics.64 In the Lithuanian Bronze Age, the combination of swastika and grass snakes is present in fibulas (brooches or clasps)65 (Fig. 6). The grass snakes were often connected with the moon symbol in the so-called moonlike fibulas.66

|

| Fig.

6. The Serpent, Spiral, and Meander sign in Lithuanian ethnographic and

archaeological examples compared to Old Europe Civilization signs. |

Lithuanian folk beliefs show a strong connection between the snakes and the sun: If you kill a snake, the sun will cry. If one kills a snake and leaves it in the forest unburied, the sun will shine dimmer for three days.67 So it is possible that, in the Lithuanian folk ornament tradition, the snake is also connected with the sun.

In their performances, today's artists try to connect the recreation of traditional patterns with contemporary scholarly interpretations of their symbolism and the social participation of schoolchildren.

This kind of reverence for the past

may be defined as traditionalism, pointing to an unwillingness to

change.68

Such modes of transcending archaization infusing the globalizing

modernity is a reaction against the spread of the rationality of the

modernistic West that, according to A. Mickūnas, is posing a threat to

the differences and identities of cultures.69

Conclusions

The scientific and cultural tradition in Baltic countries is advantageous for the evolution of a specific methodology for the investigation of the symbolism of ornaments based on the contextual revealing of the symbolism of patterns' folk names. This promotes the relevance of scholarly as well as modern artistic and poetical intertextual interpretations of the ornament tradition in contemporary culture.

Pattern names often have associative connections with mythological tradition. The discoveries of new associative links between the mythopoetical images and objects of culture, based on particular mythological logic, can stimulate the rethinking of common scholarly reconstructions of mythology as a system to explain the world.

Folklore tradition and scholarly knowledge become involved in the process of collaborative connection with modern creative interpretations of the Baltic mythopoetical tradition, especially in the annual Festival of the Autumn Equinox in Vilnius. It is important to note that even hypothetical scholarly interpretations of the meaning of traditional Baltic ornament can be taken as the base for modern creative interpretations and the invention of new traditions. In this way, a new set of intercodical relations is generated.

The

links of modern symbols with the mythic tradition suggest their actual

function not only as signs of national identity, but even much more as

the expression of cultural identity based on archaic-mythological,

interdisciplinary, and intertex-tual language associated with the

paradigms of collectiveness, traditionalism, and archaism.

Notes:

1 Bendix, In Search

for Authenticity, 183186.

2 Smidchens, Baltic Music.

3 Roginsky, Folklore, Folklorism, 4142.

4 Kristeva, Desire in Language,

66-69.

5 Genette, Paratexts.

6 Šiukščius, Mitopoetika lietuvių prozoje;

Jankauskienė, "Antropologijos ir istorijos," 105-114; Apanavičienė,

"Modernizmas lietuvių muzikoje," 195-212.

7 Jankauskienė, "Broniaus Kutavičiaus,"

68-77.

8 Celms, Latvju raksts.

9 Almeida and Haidar, "The mythopoetical."

10 Лотман,

Семиосфера,, 240-241

11 Tumėnas, Lietuvių tradicinių juostų

šimtaraštiškumas.

12 Tumėnas, The Connections; Haarman, Early Civilization.

13 Zariņa, Apģērbs.

14 Lehtosalo-Hilander, Ancient Finnish.

15

See Иванов, Отражение индоевропейской; Иванов,

Топоров,

Структурно-типологический; Амброз, О символике; Грибова, Пермский

звериный; Русакова, Традиционное; and Толстой, К реконструкции

семантики.

16 Brastiņš,

Latviešu ornamentika.

17 Bīne, Latvju rakstu.

18

The Lithuanian Institute of History (LIH), Ethnology

Department

Manuscript Archive, ES b. 1959, l. 8; The Lithuanian National Museum,

EMO 1826.

19 The National M. K. Čiurlionis Art Museum, E

2876.

20 Basanavičius, Iš krikščionijos santykių.

21 Гамкрелидзе, Иванов, Индоевропейский язык,

642.

22 LIH, ES b. 1983, l. 4.

23 Urbanavičienė, Lietuvių apeiginė,

90.

24 Elisonas, "Mūsų krašto fauna," 128.

25 Tumėnas, Lietuvių tradicinių,

204.

26 Williams, Deformed Discourse,

166.

27 Eliade, Rituals and Symbols,

62-63.

28 LNM, EMO 2193.Нячаева, Галина (ред.).

Арнаменты Падняпроуя. Минск: Бела-

русская навука, 2004.

Обoленский, К. М. Летописец ПереславляСуздальского. In

Временник императорского Московского общества истории и

древностей Российских 9. Москвa: Мoсковский университет,

1851.

29 Нячаева, Арнаменты,,

84.Летописец

30 Susvartyk,

antela,/

Bistriai plaukiodama,/

Susdūmok, mergela,/

Už manį eidama (Kazlauskienė, Lietuvių liaudies,

348).

31 Vai

ir atlėkė/ Žųsų pulkelis/ Sudrumstė vandenėlį/

Į juodą purvynėlį./

Dar

vandenėlis/Nenusistojo,/ Bernelis mergelį Jau priviliojo

(Misevičienė, Darbo

dainos, 55-57; Kazlauskienė, Lietuvių liaudies, 594).

32 Лотман, Семиосфера,

240241.Седов, Финно угры и балты, 406, 422, 453, fig. CXXXIV/24.

33 Toporov, Dar kartą, 127148; Иванов, Топоров, Аушра,

Лайма, Лаума, 72, 309, 312.

34 Ibid.

35 Рыбаков, Борис Альбертович, 1,

24-47; 2, 13-33; Gimbutas, The

Language; Tumėnas, "The Connections."

36 LIH, ES, b. 1954, l. 9.

37 Ibid., b. 1985, l. 45.

38 Kriščiūnienė, Užgavėnės, 62,

64-65.

39 Burkšaitienė and Krištopaitė, Aukštaičių,

222-226, 660-661.

40 The Russian Museum in St. Petersburg,

T-3985.

41 Карпова, Гребень.

42 Виноградов, Терминология.

43 Tumėnas, "The Visual," 78-85.

44 Иванов, Отражение.

45 LIH, ES b.1958, l. 6.

46 LIH, ES b. 1954, l. 9.

47 LNM, EMO 505.

48 LIH, ES b. 1983, l. 3.

49 Hahm, Ostpreussische, 34, 94.

50 Vaitkevičienė, "The Rose," 23-29.

51 LIH, ES, b. 1949, l. 5.

52 Slava, Latviešu, 17.

53

Kalėdų rytą rožė inžydo/ Atbėga elnias devyniaragis/

Ant vieno rago ugnelė

dega/ Ant

antro rago kavolėliai kala/ Jūs, kavolėliai, mano broleliai/

Vai jūs nukalkit

aukselio žiedą. (Valiulytė, Atvažiuoja, 70)

54 Обoленский, Летописец, 19-21.

55 Vyšniauskaitė, "Lietuvių," 68-70.

56 LIH, ES b. 1949, l. 5.

57 Ibid, b. 1953, l. 2.

58 Ibid, b. 1958, l. 24.

59 Kišūnaitė, "Lietuvių," 45.

60 Tamošaitienė, Tamošaitis, Lithuanian Sashes,

40.

61 Aarne, The Types, 425M.

62 Elisonas, "Mūsų krašto ropliai," 142.

63 Beresnevičius, "Eglė žalčių," 69-82.

64 Tumėnas, "The Connections"; PbiSaKOB,

"KocMoroHMfl."

65 Седов, Финно угры и балты, 406, 422,

453, fig. CXXXIV/24.

66 Vaitkunskienė, "Mitologiniai," 55,

fig. 31.

67 Elisonas, "Mūsų krašto ropliai," 107.

68 Hansen, "Modernity as Action," 325.

69 Mickunas, Algis, "Cultural Logics,"

147, 157-158, 163.