Copyright © 2015 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Editor of this issue: Almantas Samalavičius

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2015 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume

61, No.2 - Summer 2015

Editor of this issue: Almantas Samalavičius |

Two Patterns of Lithuanian-American

Behavior:

The Political Refugee and the Economic Immigrant

EGIDIJA RAMANAUSKAITĖ

EGIDIJA RAMANAUSKAITĖ is a senior researcher at the Center for Cultural Studies at Vytautas Magnus University. She is theauthor of numerous publications on cultural group identity and migration issues.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Elona

and Rimas Vaišnys for their useful comments and intellectual support.

Abstract

This paper analyzes and compares the behaviors of the Lithuanian

political refugees who came to the United States after World War II

with the economic immigrants who arrived after 1990. The comparison

suggests that the agents, even when they experience negative influences

from their environment, retain their original state of political

refugee or economic immigrant. The paper discusses the immigrants'

relationship to the U.S. government, to American society and their work

environment, to their relatives in Lithuania, to their immigrant

cohorts, and to the previous generation of Lithuanian immigrants.

The cultural norms and customs of multicultural America are far different from those found in Lithuania. Immigrants' living histories show that they usually do not have enough knowledge about the target country and consequently encounter considerable adaptation problems.1 Once in a new social environment, a person often notices that the environment communicates with him differently than he expected. This awareness arises when communicating at work, within an ethnic group, and in other public places. As George Herbert Mead pointed out, a person becomes aware of himself "by taking the attitudes of other individuals toward himself within a social environment or context of experience and behavior in which both he and they are involved."2 These insights encouraged future social researchers to draw attention to the investigation of a person's behavior in their specific social environment, as well as to the development of symbolic meanings in the process of communication.

The aim of this paper is to compare how the behaviors of individuals in two groups develop differently when their initial states at the time of arrival are different, comparing political refugees (the Lithuanians who came to the United States after World War II3) with economic immigrants (who arrived after 19904). What are the new social environments they face, and what are the influences they experience? Research on the behaviors of political refugees and of economic emigrants in their social environments is important for the community to encourage people to weigh more seriously their decision to emigrate from their native country. The study may encourage those who still decide to leave to become better acquainted with the public customs, policy related to immigrants, possible working conditions, and other social environments of the country to which they want to go. This research might also help estimate the duration of life in exile.

The dynamic systems theory approach used for this analysis considers the behavior of the research subjects (an individual or a group) to be derived from a state transition function that characterizes identity. This function asserts that the state of the system at the next moment of time depends on its current state and on the current environment. Dynamic system theory suggests choosing a research system (individual or group), identifying its state, and identifying all other members of society with which the system interacts as the system's environment. The theory offers a framework for analyzing the selected system in relation to three components: the state of the system, the nature of the system's environment, and the influences between the system and its environment.5 Change in a system state over time (when moving from one value to another), can arise of itself, or because of environmental influences, or because of both, giving rise to the behavior of the system.

Features specific to political refugees and to economic immigrants were selected from field research data and written sources. The written sources cover published interviews with displaced persons,6 data from interviews published on the website of the Balzekas Museum, and from the official site of the Lithuanian-American Community, as well as data published in articles by Alfonsas Eidintas, Milda Danytė, Linas Saldukas, and others. The field research was performed at a Lithuanian Saturday school located in Illinois and was designed for analysis of the economic immigrants' behavior. Group conversations (of twelve people, including six teachers, two pupils, and four parents) were recorded, and activities of art groups and various Lithuanian organizations (Ateitininkai, Scouts, religious groups, and others) were observed.7 The duration of the field research was three weeks in 2012. Additionally, a study by Daiva Kuzmickaitė on third-wave immigrants' adaptation in Chicago was found very useful. The identity of the economic immigrants was constructed using data only from those respondents of the third wave of immigration who were engaged in Lithuanian community activities, such as Lithuanian Saturday schools, art groups, and other organizations. Political refugees and economic immigrants often represent the middle and upper social strata of Lithuanian society.8

This paper 1) discusses the social environments that influenced the mentality of political refugees and economic immigrants, as well as their decision to depart from Lithuania; 2) analyzes changes in states related to influences from the environments of both groups; and 3) discusses identity issues. In conclusion, the behaviors of political refugees and economic immigrants are compared. The behavioral patterns of immigrants presented in this article can be useful when performing a broader and more comprehensive study.

Influences on the Mentality of Political Refugees

When Lithuania declared its independence in 1918, it emerged from several centuries of Russian rule. Its people were impoverished and illiterate. Moreover, the newly independent state had to create national government institutions. We are interested in what factors had formed the mental outlook of those political refugees who had been instrumental in building Lithuania. These political refugees had been among Lithuania's teachers, municipal and state government officials, clergy, professors, thinkers, writers, doctors, musicians, lawyers, businessmen, and successful farmers. Up-and-coming young Lithuanian intellectuals studied in Russia, Switzerland, and other foreign countries. After their return to Lithuania, they usually worked for local government structures and educational establishments, such as schools and universities. These individuals had an impact on their environment, and they themselves had experienced the influences of other supportive intellectuals who encouraged their creative activities.

The mental climate in independent Lithuania was not monolithic, but there was a strong unifying theme, as described by Antanas Maceina:

A nation is always a community. But in order for it to experience itself as a community, a nation's members (...) must identify themselves as belonging to the larger community and interact based on this acknowledgement, in other words, they must perceive themselves as "individuals of the same nation." (...) The nationality principle changes how an individual views another person, it changes how people interact, and it influences the outward appearance of these interactions. (...) A national consciousness seeks to express its sense of community in a visible way.9

Interwar Lithuanian intellectuals defined themselves as members of a nation and matured in an intellectually critical and creative environment. The critical discourse on educational policy during this period is revealing of the intellectual environment.

In 1926, Kazys Pakštas (1893-1960), a professor and president of the Lithuanian Geographic Society, proposed that Lithuania's educational system be based on "cultural autonomy," which would allow Lithuania's minorities to develop their own educational content. This view was supported by the Catholic intellectuals, who opposed a hegemonic "national model" of educational reforms that could change whenever a new political party assumed power.10 The "national model" of education, however, was proposed and implemented by the administration of President Antanas Smetona (1926-1940).11 This model demanded that teachers take an oath of loyalty to the state and required content specified by the state. The Catholic intelligentsia openly opposed this position, and young Catholic intellectuals (Antanas Maceina, Stasys Šalkauskis, Pranas Dielininkaitis, and others) proposed instead New Humanism, a social and political organizational model that advocated the idea of civic-minded and politically aware individuals who would be active from a sense of responsibility for the welfare of their nation.12

Another factor in the formation of the mindset of Lithuanian political refugees was the organizations that became effective vehicles for leadership training. These organizations supported family values, were engaged in educational activities, and encouraged individuals to be creative and to act on behalf of their homeland. Especially active were the Catholic student organizations, such as Ateitininkai (1911-1940), Pavasarininkai (1907-1940), and others,13 as well as various organizations of teachers, workers, businessmen, politicians, athletes, and numerous charitable organizations. All stressed the importance of education. Kęstutis Žemaitis, a priest and educator, wrote of the interwar Catholic Church "that even economic progress cannot exist without the professional and religious education of the individual."14 Ateitininkai was the largest university student organization during the interwar period, and its leaders played an important role in the intellectual, educational, and social life of Lithuania. The creative spirit of the community was supported by the social and cultural activities of individuals. Unfortunately, all of these activities were stopped by war and emigration.

Influences that Formed the Mentality of Economic Emigrants

For the analysis of the mentality of the Lithuanian economic emigrants of the 1990s, we chose the influences of the intellectuals and organizations, as in the case of the aforementioned political refugees. The intellectual environment of the Soviet period differed from that of interwar Lithuania. People did not see the patriotic-minded individuals of the interwar period in their surroundings, because these individuals were deported to Siberia, had emigrated to the West, or lived a closed life. In some cases, parents hid their family's history of exile from their children, fearing possible tensions with the Soviet regime. Meanwhile, the schools and the media spread the Marxist-Leninist worldview and Lithuanian history, such as that offered in Adolfas Šapoka's book Lietuvos istorija, was replaced by Soviet Lithuanian history. The arts, especially movies, promoted the values of Soviet youth, proletarians, and collective farmers, as well as of the Soviet soldiers who, according to this version of history, liberated the country. Mass media promoted the idea of becoming a patriot of the Soviet homeland. Changes in morality were a phenomenon of Soviet society. The Lithuanian family lost its Lithuanian traditions and Catholic education. Some artists and academicians, however, engaged in intellectual resistance and sought possibilities for maintaining the spirit of the nation. These attempts were expressed through song festivals, reading between the lines of poetry, and especially through symbolism in theater presentations.

When analyzing the activities of the public organizations of Soviet times, it becomes evident that the interwar organizations disappeared, and youth organizations were replaced by the Komjaunimas, a Communist youth organization responsible for educating youth. An ideological one-party system unified thinking. Young people born in the Soviet period naturally adapted to this environment, but some were interested in Western youth culture and looked for fissures in the Iron Curtain. Lithuanian society gradually became alienated: some citizens collaborated with the Soviet government, others resisted politically and culturally or lived a "double life." These different behaviors led to distrust and suspicion between members of society. It should be noted that these processes started during the first Soviet occupation of Lithuania and continued throughout the Soviet period.

Thus, the social environments of interwar Lithuania and the Soviet period had different influences on the community. The generation that created independent (interwar) Lithuania and remained in Lithuania after World War II was forced to live by values opposed to their own, while these same values were naturally absorbed by the younger generation of the Soviet period. The older generation's memory of Soviet repression affected public attitudes, and communist ideas in Lithuania met with heavy opposition, but the process left its imprint upon people's minds.

The Circumstances of the Political Refugees' Emigration

During the first occupation, the Soviets began a "cleansing" of Lithuanian society. Lithuanian intellectuals, especially politicians and educators, were arrested and deported en masse to Si-beria.15 Those who remained were isolated from all educational activities. Julius Šalkauskis, the son of the interwar philosopher Stasys Šalkauskis (1886-1941), remembers that "during the first Soviet occupation, neither my father nor my mother were accepted for any job. Father went to the Commissariat of Education several times (...), even offered to teach at the high school, because he could not dream of teaching at the University."16 He was not employed, however, because of his "unacceptable worldview."

Historian Alfonsas Eidintas notes that at the end of the war (1944), when the front was retreating to the West, everyone had a choice: to leave or to stay in Lithuania. For the Lithuanian elite who, in difficult wartime conditions, had carried out Lithuanian educational activities, it was not safe to stay. Some future political refugees knew about the lists of people selected for deportation to Siberia compiled by the Soviet government before the start of the war.17 In 1944, when the front line was moving to the east, part of Lithuania's population, avoiding potential new Soviet repression, left Lithuania. As noted by Raymond G. Krisčiunas, "The overwhelming majority chose to flee (...) because they had directly experienced the horrors of the first Soviet occupation (1940-41) and did not anticipate that the second occupation would be better. They fled, however, with every hope and intention of returning home after the defeat of Nazi Germany."18

A history of life in the DP camps shows that the elite who created independent interwar Lithuania tried to keep Lithuanian education and the community spirit alive.19 Members of the Supreme Committee for the Liberation of Lithuania, which was established in 1943 during the Nazi occupation, continued its activities in the DP camps.

Despite limited resources, hardships and an uncertain fate, the Baltic DPs created a rich and varied cultural life in the camps. They established schools for children and adults; published newspapers and books; maintained religious worship; organized choirs, ensembles, and folk-art guilds; revived scouting and other fraternal activities disrupted by the war; and founded civic and political organizations to advocate for themselves and for their Soviet-occupied countrymen.20

When the American government announced the Displaced Persons Act in 1948, a significant number of Lithuanian refugees emigrated to the U.S. As Krisčiunas pointed out, "the majority of the Lithuanian refugees had left Europe, with about half of the total group of 60,000 settling in the United States, thus at least partially realizing the goal of emigrating on a group basis."21

The Circumstances of Economic Emigration after 1990

In the late 1980s, political liberalization activities in society became extensive; and after more than forty years of the Soviet regime, Lithuania restored its independence in 1990. DPs participated in this process together with progressive Soviet Lithuanian intellectuals and political leaders. One of their valuable contributions was the restoration of Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, which implemented a model of higher education based on American universities. Vytautas Magnus University became the first independent academic institution in Lithuania. The Lithuanian Cultural Congress, held in Vilnius in May 1990, discussed the concepts of national culture, national identity, religious issues, national cultural strategy, and related topics.22 Following the model of interwar Lithuanian education, the idea of a national school was revived.23 However, the first years of the country's economic restructuring did not look very promising. In Lithuania, the period of 1990-1993 was marked by high inflation and economic recession.24 The media reported the public mood regarding the economic difficulties of that time. As the Lithuanian economist Eduardas Vilkas remembered: "First, it was an economic implosion, since conditions changed radically, along with commodity prices and the market (...). In winter of 1991, we lived without hot water and almost without heat because we did not have the means to buy gas and oil."25

The community demonstrated its solidarity when the Soviet Union carried out an economic blockade against Lithuania. However, the third wave of emigration began at the same time. As Kuzmickaitė pointed out in her research of Lithuanian immigrants to Chicago, "After Lithuania regained its independence in 1990, people were uncertain about their futures. This uncertainty was one of the most important factors that led them to leave their home country."26 Comparing the state of political refugees with that of economic emigrants, we see that the first were facing occupation and repression by the Soviet government, while the others left independent Lithuania because of economic uncertainty. It is not surprising political refugees sometimes find it hard to believe emigration increased when Lithuania regained its independence. We suggest the Iron Curtain went up in the minds of the generations that lived under the Soviet regime and this encouraged them to flee.

The Processes of Immigrants' Identity Formation in American Society

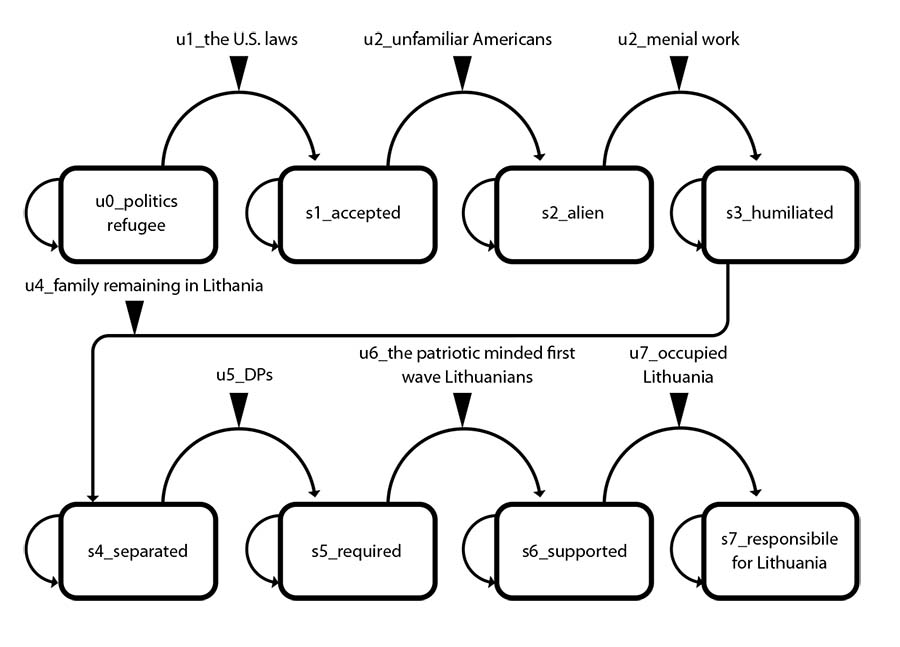

This

section attempts to identify the processes of state transition in the

two systems discussedthose of a political refugee and an economic

immigrantresulting from their initial states and from the experienced

influences of their social environments. The circles in the graphs

(Figures 1 and 2) represent the states of the research subjects at a

particular moment in time. An arc connecting two circles indicates the

value of an environmental influence that induces the state to change.

An arc that goes out of the circle and then returns to it means that,

under the same value of the environmental influence, the state remains

unchanged. In the graphs, we mentioned those influences observed by the

researcher and/or identified by other researchers in their

publications. In the graphs, we use the following symbols:

Political

Refugee

Figure 1. State transitions of political refugees under the influence of social environments over time

Figure

1 shows the state transition sequences (s0, s1...s7) that are related

to the sequences of environmental influences (u1, u2...u7).

Political refugee

The initial state (s0), presented in Figure 1, marks the state of the agent at the time he or she came to the United States as a political refugee. As mentioned earlier, the arc that goes out of the state circle of political refugee and then returns to it means that, if in the next moment of time no new influences appear from the environment, the state remains unchanged.

Accepted

The arc drawn from state s0, political refugee, to state s1, accepted, means the political refugee comes to the United States lawfully, realizes he or she is accepted by the American government (u1), and is granted the rights of a U.S. citizen.

Alien

The arc, drawn from state s1, accepted, to state s2, alien, means the political refugee, under the influence of u2, unfamiliar Americans, experiences huge cultural differences. The quotations below disclose the state of the "alien" more clearly:

Here, they usually find themselves in the cheaper dwelling areas of large cities. The Americans most of them meet are people of lower culture with little education. (...) Thus people from the upper and middle classes of the European countries find themselves forced into a lower-class environment in the United States. They do not find much in common with their neighbors at home and at work. 27

I met the Lithuanian-American family Really nice, and very warm-hearted people. They brought me home and said: "Do you want tea? Do you know what tea is?" I go back to my little room, lie down and cry bitterly. Where had I arrived? Why did I need to travel to that America? While those peopleshe was born in America, he arrived in America as a twelve- or thirteen-year-old from a really backward Lithuanian village of that time, it was still the Czarist era, where they really had not seen tea.28

During the first years of the political refugees' life in America, they depended highly on the Lithuanian-Americans who provided them temporary care (which was required by the Displaced Persons Act of 1948). There were many different experiences. The dominant experience, however, revealed significant differences in mentality. Rasa Gustaitis, who analyses the DPs' unique situation in the America of the 1950s, mentioned that "The new immigrants (DPs) did not naturally blend into the existing Lithuanian-American society or into their organizations. This is partially attributed to their refugee mentality and the hardships they faced getting established in the new country."29

Humiliated

Menial work (u3) was another environment encountered by the political refugee. Under the influence of this environment, the state of the refugee goes from s2, alien, to s3, humiliated. While describing the refugees' role in history, the Lithuanians in the Springfield website acknowledge that "most had to accept manual labor and factory positions once in the U.S., owing to language challenges and foreign degrees that were not recognized here, so they never worked as professionals again."30 The following quotation helps to take a closer look at the refugees' feelings.

How did you succeed in adapting to the local circumstances? Probably with a lot of difficulty. Since our values were slightly different. Perhaps it was the work, to work in a factory. I wanted to be somewhat human, more than just [live] for work, when you wake up, go to the factory... You know you have to work, that you have no other choice. It was difficult. For me, books were important; it was important to go to the theater, to a concert. Where we lived, people weren't interested in those things.31

Separated from family

The arc that goes from state circle s3, humiliated, to state circle s4, separated, means a change in state under the influence of a DPs' family remaining in Lithuania (u4). For a number of years following emigration, the DPs did not have any information about their families or other relatives in Lithuania; their fates were unclear.

Required for his group

The arc that goes from state circle s4, separated from family, to state circle s5, required for his group, marks changes in the state of the agent who is influenced by positive attitudes towards him or her from other DPs (u5). The DP community perceived its mission as the liberation of Lithuania, and this encouraged everybody to work towards this goal. The following quotation represents activities by DP community members related to the preservation of the community and Lithuanian culture:

My parents were very active in Lithuanian activities in Chicago. My father was a member of ALIAS [a Lithuanian engineers association], Lithuanian professors association, and several other organizations. My mother was a member of Lietuvos Dukterys, BALF [Baltic-American Freedom League], the Chicago Lithuanian Women's Club, Draugas, the Balzekas Museum and other organizations. They were supporters of children's charities and the Lithuanian Opera.32

Supported by the first wave of Lithuanian immigrants

The arc drawn from state circle s5, required for his group, to state circle s6, supported, indicates a change in the state of the agent while experiencing the support of the previous generation (first wave) of patriotic-minded Lithuanian immigrants (u6), who had created Lithuanian schools and parishes and published Lithuanian newspapers and books.33 This infrastructure enabled further Lithuanian activities, which were significantly increased by the DP generation. The Lithuanian-American Community was established by DPs, "founded on the principles set forth in the 1949 Lithuanian Charter of the Supreme Committee for the Liberation of Lithuania, urging every Lithuanian to preserve and promulgate his or her cultural heritage, language and traditions and to preserve the existence of the Lithuanian nation for future generations."34

Responsible for Lithuania

The last environment of a political refugee shown in the first graph is u7, occupied Lithuania. This environment inspires the transition of state from s6, supported, to s7, responsible for Lithuania. As the aforementioned Lithuanian website indicates, most DPs were professionals and officials of formerly independent Lithuania and felt an obligation "to preserve Lithuanian identity and culture abroad while their homeland was wiped from the map." In the late 1980s, when the struggle for Lithuanian independence began, and after Lithuania gained its independence in 1990, members of the Lithuanian-American Community assisted with expertise in numerous ways: they served on the staff of the new Lithuanian Mission at the United Nations, made a great effort to foster Lithuania's membership in NATO, and performed many other political and cultural, as well as educational activities.35 Therefore, we can conclude that occupied Lithuania encouraged political refugees to maintain their original state of responsibility for the liberation of Lithuania and remain committed to Lithuania. This explains their activities in exile.

The Economic Emigrant

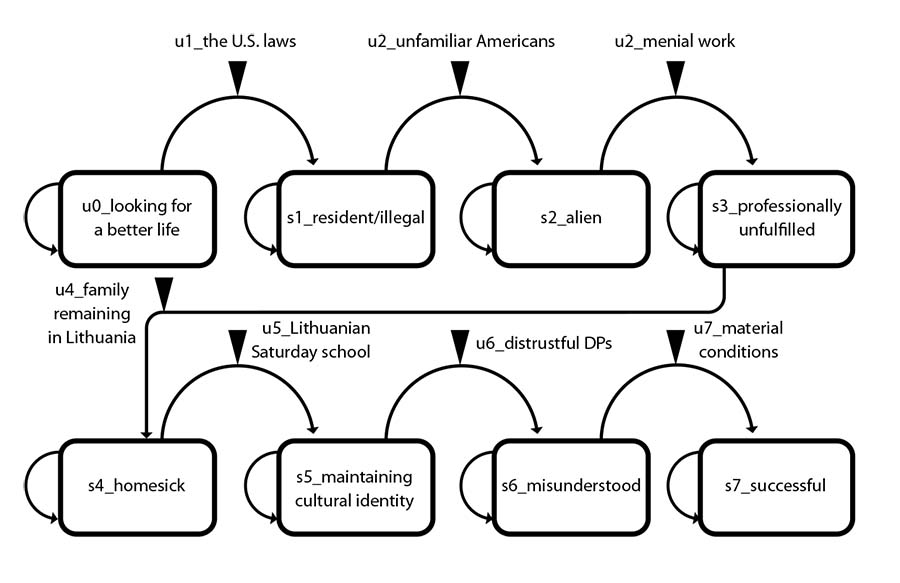

Figure 2. State transitions of economic emigrants under the influence of social environments over time

Figure

2 shows the state transition sequences (s0, s1... s7) that are related

to the sequences of environmental influences (u1, u2... u7).

Looking for a better life

The initial state (s0), presented in Figure 2, marks the state of the agent at the time he or she came to the United States looking for a better life. The arc that goes out of the state circle of economic emigrant and then returns to it means that, if in the next moment of time no new influences appear from the environment, the state remains unchanged.

Resident/illegal

The arc drawn from state circle s0, looking for a better life, to state circle s1, resident/illegal, shows changes in the state of the economic immigrant under the influence of U.S. laws (u1). The quality of life differs for those Lithuanians who come to the U.S. under an employment contract or as winners of the green card lottery from those who leave Lithuania as tourists and do not return. The illegal stranger lives in fear of deportation and avoids communication with the American public.

Alien

Like the political refugee who came after World War II, the economic immigrant faced an unknown American society (u2). Under the influence of this environment, state s1, resident/illegal, goes to state s2, alien. The state of "alien" naturally arises on arrival because of insufficient knowledge of the English language and American culture. According to a second-wave immigrant who commented on the behavior of third-wave immigrants, "they are not familiar with American values and, naturally, do not understand them." (Julija)

Professionally unfulfilled

The arc drawn from state circle s2, alien, to the state circle s3, professionally unfulfilled, expresses the state transition of the agent when he or she faces a menial work environment (u3).

Many Lithuanian professionals (educators, cultural workers, and engineers) who immigrated to the U.S. at the beginning of the 1990s were forced to take menial work as housekeepers, domestic servants, factory workers, unskilled construction laborers, and others. In most cases, many of them found themselves professionally and intellectually unfulfilled, because they were unable to practice their professions. This situation is similar to that of political refugees. The economic immigrants of the 1990s frequently worked at jobs that employed international groups of immigrants from Eastern Europe and other locations. While communicating within these groups over time, they adopt their habits, in this way increasing the distance between themselves and Americans, as well as Lithuanian- Americans (here, the political refugees generation and their children).

Homesick

The arc from the state circle s3, professionally unfulfilled, to state circle s4, homesick, shows the transition of the state of the economic immigrant when thinking about his or her parents, children and/or other family members who remained in Lithuania (u4). Although modern technology allows communication over a long distance, it cannot replace daily face-to-face communication. As per the third-wave immigrant, "The first four years, I could not find a place for myself and felt remorse for my abandoned parents... And then, somehow, it all went away; now it seems that everything has to be just the way it is." (Kamilė)

Maintaining cultural identity

As in the case of a political refugee, an economic immigrant is looking for the cultural and social environment of his or her native community members who have had similar experiences in exile and engage in Lithuanian cultural activities. The arc drawn from state s4, homesick, to the state s5, maintaining cultural identity, indicates that the economic immigrant, under the influence of Lithuanian Saturday school (u5), meets his own cultural needs and is able to maintain a Lithuanian identity in his or her children. In addition, it should be noted that most of our research participants are Lithuanian professionals in culture and education. Thus teaching in a Saturday school satisfies their professional ambitions and also helps increase their self-esteem. As a teacher related, "In everyday life, we have to adapt to the environment, whereas the environment is following us here." (Alina) The quotation below shows the variety of activities the teachers and parents' committee members participate in:

I work all week, come home at eight each night, wake up at six o'clock on Saturday morning, and go to school. (...) We take care of the school inventory, handle books and write texts in a school yearbook, organize the Christmas celebration, and so on. (...) Everyone is doing this here. (Kristina)

Parents were proud of their ability to donate their own finances for the school. A representative of the second-wave descendants, who was born and raised in America, pointed out that "Donating your money to educational, children's, and leisure organizations is characteristic of the whole Lithuanian-American community, because donations are a part of American culture." Teachers told stories of their first years in the U.S. According to a discussion-group informant, "I was everywhere here; I wanted to be needed very much. [...] We brought everything here the best we could, both historical and current knowledge, and we have taught it in this school." (Alina) Maintaining an ethnic identity becomes an important value for the individual and group. As it was highlighted by a teacher, "Here in America, we will preserve the Lithuanian language and culture much longer than you will in Lithuania."

Misunderstood

While participating in a community of Lithuanian-Americans, an economic immigrant meets values developed by a generation of political refugees. The arc going from state circle s5, maintaining his cultural identity, to state circle s6, misunderstood, shows the state transition of our agent when he or she meets distrustful DPs (u6), who call the new immigrants tarybukai (Soviets). The respondents report an impression that, from their point of view, the DPs draw a line between themselves and the economic immigrants and force economic immigrants to experience exclusion. The following quotation describes the state of an economic immigrant related to this experience:

I communicate with the dipukė (DP woman) who helped me very much. When I wanted to learn English, she drove me every time to the teacher, because it was a long way to walk. She was spending her time and did not receive payment of any kind from me. And despite the fact that she helped me so much, she used to say, "You're an ateivė (a stranger), and you will always be one." At first, I felt uncomfortable, but then I got used to it. (Martyna)

Successful

The last environment of an economic immigrant shown in the graph is material conditions (u7). Under the influence of this environment, the state of our agent moves from s6, misunderstood, to s7, successful (financially secure, able to support his or her family, and to see the world). It is equally important for economic immigrants to raise their social status in the eyes of acquaintances in the U.S. and those living in Lithuania, including relatives. Thus, the economic immigrants, even while experiencing negative influences from their social environment in exile, continue to operate in the direction of a better economic life.

Discussions on Identity

Dynamic systems theory is designed to find the patterns of behavior of the system in its environment. The state transition/identity function theoretically describes a complete set of the behaviors caused by all possible sequences of influences and all possible initial states. The state sequences of the agents, represented in this paper (Figures 1 and 2), are an approximation of reality, because they highlight only those states and influences observed by the researcher. If the researcher could explore the facts in more detail and review all potential values of the environmental variables, as well as associated values of the state variables in respect of time, the complexity of the cases would fully disclose the identity of the system concerned.

The application of dynamic systems theory can help us consider the possible behaviors of individuals or groups in various environments. For example, what changes would occur in the behavior of political refugees if they had not met like-minded individuals (other DPs) in their environment and/or if the first wave of Lithuanians had not supported them? How would the behavior of political refugees change, if Lithuania regains its independence? (By the way, this state has been tested by time. Many DPs realized they had lost their mission in life when Lithuania regained its independence in 1990). How will the behavior of economic refugees change if their economic conditions are much worse than expected and if there are no like-minded individuals engaged in Lithuanian activities?

In addition, it would be important to consider how the initial states of political refugees and economic immigrants influence their decision to encourage their children to take care of their own and their children's ethnocultural identity. It is likely that children born in the United States, whose parents already speak English, spend more time in an American cultural environmentschool, school friends, and leisure activities. In the future, will they be more willing to communicate with a local community or with an ethnic community? Throughout the history of Lithuanian immigration to the U.S., Lithuanian cultural and educational activities, supported by the new waves of immigrants, have taken place. What would happen to the current Lithuanian community through time if the immigration of Lithuanians to America stops?

Research on the states and environmental influence interactions over time explores the dynamics of identity. We can assume that, over a period of time (four to five years), our agents adapt to their environments so they become less sensitive to the negative influences of the environment and become increasingly involved in supportive environments. Other possible changes of behavior are related to newly emerging environments. For example, with time, immigrants get a chance to participate fully in the intellectual life of the country. This example is relevant to political refugees; but it can also be found among the latest economic immigrants, although much less frequently, perhaps because they have not been here long enough.

Conclusions

Political refugees and economic immigrants arrived in the United States with different initial states. Political refugees soon realized that they would be unable to return to occupied Lithuania and undertook the struggle for its liberation. Economic immigrants expected to create a better life for themselves and their families in America. It is likely that the initial states of the agents accorded with their further behavior in migration. Overcoming the complicated process of adaptation to a foreign community, the agents remain committed to their original purposes. Political refugees always remained committed to free occupied Lithuania and engaged in Lithuanian educational as well as political work. Economic immigrants usually seek to create material wealth, which would allow them to support their families and see the world.

In a hostile environment (encountering an unfamiliar society and menial work), the states of political refugees and economic immigrants are suppressed; they feel themselves alienated and humiliated, so they look for their native communities, where they meet people of the same fate (political refugees/DPs or economic immigrants).

Close circles of other political refugees or other economic immigrants become the environments that help our agents restore their state in the case of negative influences. During communication within these groups, their members manage to maintain their cultural identity and consequently help enhance their self-esteem.

The environment provided by political refugees and economic immigrants defines a wider native community that has played a significant role in the process of the adaptation of newcomers. Both were able to take advantage of Lithuanian cultural heritage in exile (Lithuanian organizations, the parish schools, museums, archives, and publications). However, economic immigrants and DPs faced different social conditions, as well as the different mentality of an earlier wave of immigrants. Owing to the DPs' significant Lithuanian political and cultural activities, they managed to attract patriotically minded representatives of the first wave of immigrants, and the latter became supportive when realizing the goal of the liberation of occupied Lithuania. Economic immigrants experienced a lack of acceptance from the second wave of immigrants, and their integration into the Lithuanian-American community has not been so rapid.