Copyright © 2017 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Editor of this issue:Almantas Samalavičius

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2017 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume

63, No.2 - Summer 2017

Editor of this issue:Almantas Samalavičius |

Vilnius Versailles:

Sic Transit Gloria Mundi

Almantas Samalavičiusr

Abstract

The article discusses how an impressive seventeenth century

baroque urban complex, ambitiously called the Antakalnis Versailles

by art historians, came into being alongside Vilnius. Reviewing

the historical particulars of the suburbs architecture and its baroque

legacy, the author shows that its nickname is neither

the creation of a nostalgic imagination nor an empty and provincial

ambition. The unique ensemble of suburban residences

really was built by magnates of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy in

emulation of the traditions of the European baroque period. Although

it experienced only a short period of glory, this impressive

and artistically valuable architectural ensemble is an unequivocally

meaningful expression of baroque cultures urbanization

and artistic processes in Vilnius.

The

Versailles of Antakalnis

Vilnius is frequently and not without

some reason called a baroque

city, even though many of the architectural structures of

this epoch and style have decayed over the years and given up

their spots to less impressive structures of later time periods.

Antakalnis, one of the oldest suburbs of the capital, has long

since become part of the city, so observing suburban characteristics

in the contemporary urban fabric of this part of the city

would be difficult even with the help of a flexible imagination.

The territory of todays Antakalnis is completely urbanized, covered

mostly in not particularly attractive buildings constructed

in various twentieth-century periods, and apartment buildings

that sprang up after the war. True, eclectic-style villas that had

appeared somewhat earlier line the banks of the Neris; however,

in recent times they are more and more frequently visually

pushed aside and overwhelmed by the glass facades of post-soviet

period architectural structures. Fragments of the spirit of

the former suburb are at least expressed in the mass of the luxuriantly

forested hills, the winding narrow streets and the tangle

of variously-sized buildings. Because of the unfavorable historical

development of Antakalnis, the glory of the conglomeration

of fashionable suburban residences that were constructed in the

second half of the seventeenth century was quickly lost. On the

other hand, even with the changes in this part of the citys visual

character, a certain spirit of the place was preserved by several

particularly impressive structures. Among them one can include the

churches of St. Peter and Paul and Christ the Redeemer,

and the Sluszko and Sapieha palaces, as well as the

baroque park bordering them, which, hopefully, will finally be

recreated with the restoration of Sapieha Palace.

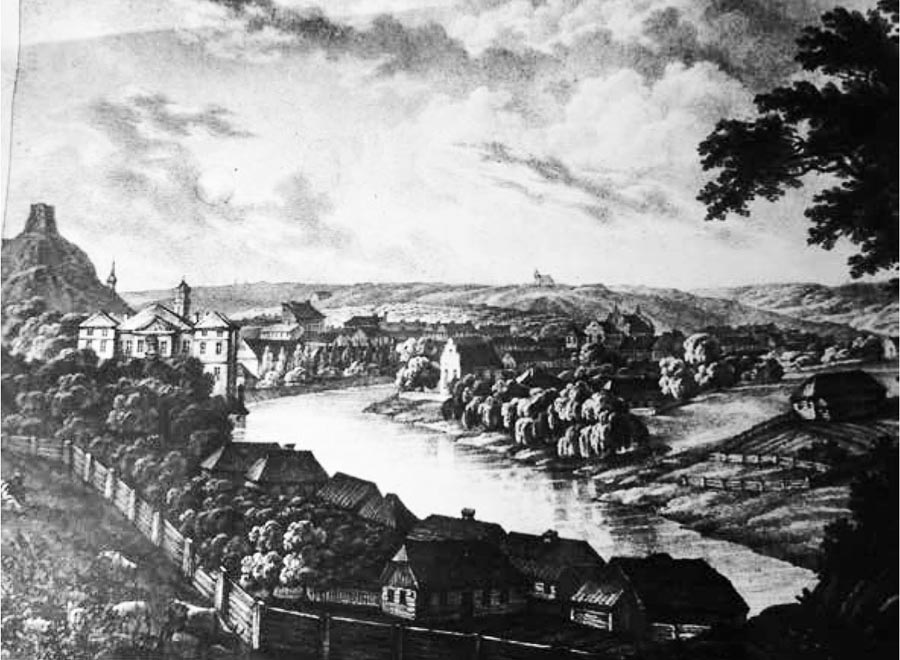

Panorama with

Antakalnis Hills

The architectural secrets of Antakalnis can be found gradually, one after another, particularly since they are all surrounded by an inexpressive and unmemorable context of modernist or simply eclectic structures. For example, walking or driving from the heart of Vilnius in the direction of the famous St. Peter and Paul Church (for some time now requiring visitors to get past the emergency situation of Gediminas Hill), a Palladian-style structure briefly flashes by. For several centuries it is known under the name of Sluszko Palace. Even if crumbling, with an appearance that has been altered many times and lost its earlier representative look, it clearly stands out in the bland architectural surroundings past the Vilnelės confluence and the square next to it is a succession of grim, unappealing brick and stone buildings darkened by dust and dirt. On the other side, across from the intersection and the street leading down to the Neris, looms the so-called Sluškų apartments a nearly perfect example of cheap but shiny and effective post-Soviet new construction of glass and reinforced concrete.

From Kosciuška Street, the palaces arent easily seen, particularly since only a small portion is seen through a break in the wall of the architecturally insignificant former barracks buildings from the time of the czarist empire. The coarsely shaped new concrete stairs leading to the edge of the Neris River are a gloomy contrast to the unforgivably neglected palaces, painted in various colors, newly plastered in spots, worn by sun, rain and wind, but still to some extent preserving their former elegance. The eclectic accumulation of buildings lined up on the bank, condemned by some art critics as early as the period between the wars, now looks even more chaotic and visually aggressive. It is the regretful result created by the alliance between current architectural vision and careless post-Soviet construction process.

Researchers of the architecture of Lithuanias capital, almost without exception, emphasize the uniqueness of Antakalniss landscape and what a remarkably harmonious relationship there once was between nature and architecture. The traces of this extremely subtle interaction are still clearly visible, particularly at the time of year when the trees of the surrounding hills have not yet thrown off their thick and colorful leaves. The wellknown art historian Vladas Drėma, usually a particularly dry, sober, and laconic scholar (truly the opposite of his older colleagues the art historian Mikalojus Vorobjovas or Jurgis Baltrušaitis Jr.), without hiding his enchantment, wrote in his magnum opus Dingęs Vilnius:

The largest and most beautiful suburb of Vilnius is Antakalnis, which was completely developed as early as the fifteenth century. It is arranged on the wide terrace of the Neris River, parallel to its left bank, on its other side abutting a large range of hills overgrown in woods. A road from Vilnius to Nemenčinė and on to the north goes through Antakalnis, which continues about five hundred meters from the confluence of the Vilnelė to the Grand Dukes residence in Viršupė <...> Antakalnis is ruled by four jurisdictions, but it does not belong to Vilniuss magistrate. The clear waters of the Neris and the resin scent of the Sapieginė Forest determine Antakalniss natural beauty, pleasantness, and peacefulness, providing all of the conditions for rest and carefree living. The fact that this suburb is so close to the city prompted nobles, solid and middling gentry, distinguished church officials, and city patriarchs to build palaces in Antakalnis, their summer homes, villas (lukiškės) and to spend their days of leisure there.1

In a book analyzing the architecture and art of Vilniuss St. Peter and Pauls Church, one of the scholars of Vilniuss history of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Stasys Samalavičius, together with the author of the present article, pointed out the uniqueness of the surrounding areas urban character:

The Versailles of Antakalnis arises in a distinctive natural landscape. On one side, the Neris River with high riverside hills overgrown with trees and shrubbery bounds Antakalniss space (just where the Sluszko palace arises); from the other side, from Gediminas Hill the ancient road leads upward, buttressed by the stone walls of St. Peter and Pauls Church, which are extended by the building of the Canon Regular of the Lateran monastery. Farther to the northeast, on the top of the hill, is the grouping of the Sapieha Palace, while the Trinitarian Church, built at almost the same time with funds provided by the Sapiehas, adjoins it. The suburban residence and the sacred structures make up Antakalniss integrated urban landscape, even though it was formed spontaneously as well.2

The charm of this particular location, even though significantly dimmed in the period of the czarist Russian colonization (when the city stopped being a capital) and not changed much during the years of the Polish occupation, awakened other architectural historians imagination, too. Vorobjovas, who once provided difficult- to-better insights on the genius loci of Lithuanias immortal capital, has also emphasized the extraordinariness of the natural and architectural structure of Antakalnis. During the Second World War, Vorobjovas elatedly wrote:

Following Moscows attack, at the end of the seventeenth century the building of aristocratic palaces flourished in Vilnius. Lithuanias nobility attempted to rebuild what had been destroyed during the war years, and at the same time sought to embody the emphasis toward noble grandeur and plans that suited a matured baroque spirit. A particularly characteristic monument to those aims was St. Peter and Pauls Church in Antakalnis. Incidentally, Antakalnis was mostly associated with this new period in the history of aristocratic palaces. Michael Pac raised St. Peter and Pauls Church there, as if his own grandiose mausoleum, at the same time building a luxurious palace in the center of town, next to Town Hall Square, while two other magnates, Sapieha and Sluszko, created their suburban residences in Antakalnis. They used this remarkably beautiful location not just as scenery to incorporate around their buildings: Antakalniss nature was understood as a moldable material from which artists were to forge new architectonic imagery.3

However, the art historian was by no means a nostalgic romantic, and his sincere enchantment with the locations past did not overcome a sober assessment of historic realities. Vorobjovas emphasized that the complex and turbulent history of Lithuanias Grand Dukes would not allow all the ambitions of the nobility of that time to be embodied, and the grandeur of the architectural Versailles to be repeated in Vilnius (even if to attempt extraordinary canonical monuments was characteristic of the baroque epoch); it was not the lack of enthusiasm among Lithuanias aristocrats, but the inauspicious historical conditions. Many magnates dreams were left abandoned, and much of what was created at the end of the seventeenth century was mercilessly wiped from the surface of the earth by nineteenth and twentieth century barbarians foreign colonizers. This is how tasteless suburban villas, grim standardized apartment buildings in the style of Soviet modernist architecture, and most recently particularly cheap construction apparitions of the new architecture appeared in this neighborhood of the Neris. With more than seven decades gone by, one can only repeat Vorobjovass words written during World War II , that Vilnius has fallen into strangers hands; Antakalnis, according to the art historian, is, in a topographical respect, a distinctive and remarkable location that cries out to our urban chaos and create a new architectural ensemble that suits our capital. 4 This cry of a Vilnius-loving soul, unfortunately, has apparently remained unheard to this day, and sounds more like a reproach to Vilniuss post-Soviet urban planners. The urbanists lack of far-sighted insights also had the result that after the restoration of independence, suitable attention was not paid to this unique part of Vilniuss urban structure. An impoverished architectural vision and weakened ambitions for urban design determined that todays Sluszko Palace with all of its eclectic and chaotic urban surroundings continues to reflect two apparently different but peculiarly similar effects of the czarist imperial and the Soviet/ post-Soviet epochs on the thinking of urban design and their astonishingly similar paradigm of action. Both of them ignored the centuries-old uniqueness and distinctiveness of Antakalnis.

The Historical Drama of the Sluszko Palace

As researchers of this location have

shown, there was a different

noble family of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy in this spot earlier.

The original palace, built by the Kiszkas, had several owners: at

first it was given to the Grand Duke Vladislaw Waza, and he

passed it on to the disposition of the Pac family (somewhat earlier

a wooden representative mansion belonging to the Pac family

stood next to it). Finally, in 1690 they sold their mansion to

Dominik Michael Sluszko. The new owner tore down the old

building. In the last decade of the seventeenth century, it was

replaced by a massive, large-scale square structure with corner

towers built upon a specially constructed peninsula. The Polish

art historian Euzebiusz Łopaciński, writing about this impressive

baroque structure before the Second World War, considered it

among the most impressive mansions in all of Vilnius.5

The Neris riverside with

a view of Sluzko Palace.

Nineteenth century

lithograph by unknown author.

One of the researchers of the palaces history, the Catholic priest Tadeusz Rogala-Zawadzki, wrote:

This noble structure, according to the taste dominating at the time, should have been surrounded by water and a moat, and given the palace an impression of being isolated from its surroundings. After all, the palace had been built on the channel of the Neris, which had earlier washed the building itself, and its possible a canal with water separated it earlier from the shore. One must not forget that it was the era of Louis XIV in France, which had an extremely strong effect on all Europe.6

According to this historians information, the Sluszko Palace was conceived as a majestic structure consistent with the scope of a baroque spirit and perfectly arranged in Antakalniss landscape. Rogala-Zawadzki proposed the hypothesis that According to that time-periods architectural taste, the river bank should have been covered in cut stone, and the building should have been bordered with a balustrade of hewn rock.7 Analogies with suburban baroque villas in Western Europe show that the buildings surroundings could have been formed with the help of springs, as the nobility of Italy and France had decorated their suburban residences with a particular high culture of water aesthetics. Beyond the Sluszko Palace, on the other side of todays Kosciuška Street stretched a decorative Italian style park as it is referred to in historical sources with lagoons and canals. Like in Italian suburban villas of that period, the basic compositional component of the ensemble of architecture and nature was the palace, accompanied by various auxiliary buildings, offices, and other objects. According to this architectural historian, although both the Sluszko and Sapieha mansions were built in the epoch of Louis XIV following the example of Versailles, the planning for the Antakalnis parks did not seek an infinite perspective. They were considerably more ordinary, simpler, more natural, and harmonized more with the natural texture of this suburbs landscape. This aspect of the Sluszko Palaces landscaping was accented by authors who wrote about this during the Soviet years, the architect Antanas Pilypaitis and the historian Adolfas Raulinaitis, who said:

A large complex orchard-park was arranged around the palace, including the hill beyond todays Kosciuška Street, which was not there at the time. Its arrangement required a considerable amount of work digging the earth because the location had a complex terrain <...> The water mirrors canals and ponds had an important role in the composition of the park. According to the green construction principles of the time, the parks composition should be subordinate to the ensembles center the palace standing next to the Neris River.8

Clearly the palaces owners did not lack in baroque ambition. The Latin inscription that once greeted visitors attests to this. In Latin, it read as follows:

Montes Depuli, Aquas Viliae Edomui, Aera Absg: Svggestu Collium Superavi, Victrix Elementorum, Facta Sum Domus, Quietis, Socia Antecolensis Heroum Augustalis Hic Sub Luna Amica Quieti, Dea Pacis, Togam, Sub Armis Ostoja Bellona Sagum, Ad Tranquillitatem Componito.9

Many authors who had written about Vilniuss so-called Antakalnis Versailles mentioned that the relatively very short time period of the Sluszko Palaces prosperity was determined by a curse. One of the nobles whom the magnate Dominik Sluszko had wronged, having lost his wealth and been condemned to poverty, wrote on the palaces gates: Haec excellsa domus, plurimus extructa rapinis corrnat, aut alter raptor babebit eam (Let this excellent building, built with an abundance of plunder, fall down or go to another usurer). Although this kind of archaic metaphysics could bring a smile to a contemporary atheist, it must be observed that fate really was unkind to the palace of the noble Sluszko family. From the beginning of the eighteenth century, its owners changed constantly and the palace continually declined, losing its aesthetic expression. After the death of Dominik Sluszko it was sold to his creditors. For some time it stood without being looked after and lost its former beauty and charm, although in 1705, after the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Russian czar Peter I stayed there along with his staff, which testifies that its condition was still sufficiently good. Later, Kristupas Puzinas acquired the palace in the third decade of the eighteenth century, after which the Potocki nobles purchased it. From them, the palace passed to Vilniuss Piarist monastery, and in 1766 they sold it to the Polish duke and composer Michael Casimir Oginski, who quickly concerned himself with needed renovation of the neglected, nearly ruined palace. According to the historian Rogala-Zawadzki, From the 1756 inventorys description, we know that at the time the buildings ceilings and roof were caved in, the stoves dissembled and looted, the walls rotting, the foundations sagging, and all of the cottages were nothing but ruins.10 All the same, the historian interpreted the palaces history with a considerable dose of mysticism, connecting the unfortunate events with the curse of the noble mentioned above: when the Lithuania Grand Duke and Polish king Jan III Sobieski stayed at the palace, a heavy block of stucco that fell from the bedroom ceiling only missed hitting the ruler by a miracle. In addition, while climbing the palace stairs, the czar Peter I fell and injured himself. According to Rogala- Zawadzki, the uninhabited palace turned into a terrifying estate, where the living visited and the ghosts made their home.11 Finally, after a person named Zaikowski had equipped a brewery there in 1800, a boiler exploded and a number of workers were injured, and following this event the business went bankrupt. Yet another event that, given enough imagination, can be ascribed to the fulfillment of the famous prophecy...

In 1794, revolutionary headquarters were established in the Sluszko Palace, and bullets were cast there. In retribution for this anti-colonial activity, the czarist government confiscated the palace and rented it out to a local merchant. For a while a lumber mill, a distillery, and a brewery worked there. In the 1830s, a czarist artillery regiment settled in Sluszko Palace; later it was turned into a warehouse. Afterwards a hospital and then a jail took over. Understandably, all of these changes in function did not improve the state of the palace and most likely contributed to its decline.

Contrary to assertions by some of the locations architectural researchers, in the second half of the nineteenth century the palace had three stories. This is demonstrated by the Russian engineer Prokofjevs plans of the structure at that time, which the historian Feliksas Sliesoriūnas came across in the Lithuanian Central Archive.12 However, its obvious that the palace continued to decline at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1903, the czarist government ordered the northern driveway, including a particularly decorative gate, destroyed, and the entire palace surrounded by a military fence, which unfortunately still mars the palaces silhouette today. The remodeling and reconstruction campaign continued during the Soviet years; at the end of the 1950s, the Sluszko Palace was handed over to a machine-operator school. It was only relatively recently that the cultural function of the palace was remembered and several Lithuanian music and theater academies subdivisions were housed in this considerably worn and neglected palace. The government allotted two million litas to the palaces renovation, but such a small sum was not enough to significantly improve the state of the building.

When the palace will be finally

appropriately restored is only

a matter of guesswork. On the other hand, it is questionable

whether its at all possible to recreate even a somewhat authentic

image of a baroque villa. Let us not forget that thanks to the

reconstruction, the palace has grown by a floor, i.e., at this time

there are four floors; its former interiors are irretrievably

destroyed;

the building is imprisoned in a simply horrifyingly unsuccessful

architectural surrounding; and it is even difficult to

see while walking by on Kosciuška Street. Nevertheless, ignoring

these adverse circumstances, reestablishing at least a part of the

Sluszko Palaces former majesty is not just possible but imperative.

With a properly restored palace and the external decor recreated,

both the palaces silhouette and the contour of the peninsula once

created there would be revealed. Although Vorobjovass hope that

the low-value structures evoking barracks located next to the

palace would be razed, it is questionable whether this could take

place in the near future, given the status of the surrounding real

estates ownership. However, all is not yet lost. If the state

government would have sufficient resolution to rebuild the palace,

that is, to allot the means to suitably restore the palace, the

structure,

even in todays urban surroundings, could sound like a

distant but audible echo of the cherished majestic aesthetic ideals

from the baroque epoch. To Vilnius residents it would recall the

former suburbs short but impressive period of baroque glory.

Sluszko Palace. Photo by

Jonas Grikienis.

Sluszko Palace. Photo by

Jonas Grikienis.

Sluszko Palace. The main façade. Photo by Jonas Grikienis.

Current view of Sluszko

Palace.

All photos except those

attributed to Jonas Grikienis are authors.

Façade of Sluszko

Palace. Photo by Jonas Grikienis.

Current view of Sluszko

Palace.

The Sapieha Palaces Rise, Fall, and Resurrection

Beyond St. Peter and Pauls Church and next to the Canon Regular of the Lateran monastery stretches the grounds of another noble family of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy the Sapieha family with an impressive palace and the Trinitarian Church built with their funds. A wooden palace stood here as early as the first half of the seventeenth century. In 1691, the palace built by Jan Casimir Sapieha rose in its place, distinguished by a particularly sumptuous interior decoration. Vorobjovas wrote:

From other sources it is known that the painted decorations were done by the Italian Del Bene. His frescos have survived, incidentally, in the St. Casimir Chapel (in the Vilnius Cathedral A.S.) as well as in the Pažaislis monastery; his huge composition in the Sapiega Palace, The Feast of the Gods, is particularly well-known. Other decorations are mentioned in that dining hall, as well as in a bedroom, including stucco ornaments (some of them gilded) and overdoors with paintings in molded frames. Further, the inventory mentions large stoves with colored tiles (mostly green) and chimneys as well as figures and architectonic decorations. In some places there were parquet floors of ash, and marble floors in one room. The walls of one room were covered in majolica tiles, and the stove built in a pale blue tile with the coat of arms.13

Although the newest information shows that the frescos authors name was not Del Bene,14 the majority of Vorobjovass evaluation was based on information from archival sources that are still considered valid. He was, incidentally, one of very few Lithuanian authors who investigated the history of Antakalniss structure in the first half of the twentieth century. Today its history is better known, although some aspects have not yet been thoroughly researched, so more surprises are undoubtedly to come.

The Sapieha Palace, for various reasons including the Northern war that began soon after, flourished for a very short time. The architect-restorer Evaldas Purlys and the Polish art historian Piotr Jamski described the convolutions of the palaces history and the compositional arrangement of the majestic and imposing building with its baroque-spirit park in their articles published in Kultūros barai, even though at that time the possibility of its recreation was unclear.15 The latter associated the settling of the Sapieha family in Antakalnis with the twists and turns in the political career of Jan Casimir Pawel Sapieha, particularly since, with the entire Sapiega family being close to the Polish king and Grand Duke of Lithuania Jan III Sobieski, they managed to quickly establish themselves in the highest government and economic posts in the Grand Duchy.

A well-founded question could be asked why, with more than a quarter-century gone by since Lithuania shook off the Soviet regime, does the restoration of buildings of significance in the states history and identity continued to be delayed? Frequently, there are attempts to justify the sluggishness by appealing to the states economic situation, demonstrating that apparently economic shortages interfere with the restoration of palaces and parks and so must wait for better times. There is only the question if, while eternally waiting, anything will be left to restore at all. However, it can finally now be added that in recent years things are looking considerably better for Antakalnis. Although the condition of the Sluszko Palace, which is used by Lithuanias Music and Theater Academy, still leaves an oppressive impression, restoration has begun on the Sapieha Palace. The results of no small amount of already completed restoration work, are now visible. On the other hand, recent years have conferred new information about the history of the Sapieha Palace in Antakalnis. According to the newest researchers of this architectural object, the art historian Rūta Janonienė and the architect Evaldas Purlys,

The Sapieha jurisdiction in Antakalnis occupied a large plot, from the Neris, through the Antakalnis hills to Rokantiškės, and beyond to the Vilnia River. On the south, the Sapiehas land bordered with the territory of the noble Pac family of Lithuanias Grand Duchy (the ensemble of the Canon Regular of the Lateran monastery and St. Peter and Pauls Church stand in the Pac territory). Before 1671, the land where the Sapieha Palace was to stand belonged for some time to the hetman of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy and governor of Vilnius, Michael Casimir Pac. Sapieha began to settle in the territory of his palace at the end of the seventeenth century, during his period of greatest power and activity. The Sapieha jurisdiction was formed from at least two owners lands purchased by the Lithuanian Grand Duchy Great Hetman and Vilniuss governor Jan Casimir Sapieha.16

Jan Casimir Sapieha purchased the territory belonging to the Manvydas family, along with some land close by that belonged to the Jesuit novitiate. In 1691 the construction of the new palace on the purchased lots began. The palaces researchers added that the piece of land belonging to the latter Sapieha was noted on Johann Georg Maximilian von Fusterhoffs plan of 1737.17 Jamski has pointed out the influence of the French context of that time on the Sapieha Palaces park. According to him,

In the Antakalnis ensemble, its designer based his work on the newest French examples from Le Notres work. A parterre flower bed was arranged across from the palaces territory; further on were water reservoirs and in the distance, hedges of trees. This conformed to the principles of the highest degree of comparison of garden vegetation. The whole, with the main avenue and side avenues, illustrated a recognizable type of multiple center lines and multiple perspectives from the surroundings of Louis XIV.18

Two foreigners whose names left marks in Lithuanian culture the Italian architect Giambattista Frediani and the sculptor Pietro Perti are tied to the construction and decorative work of the Sapieha Palace. The first was known as a military engineer who, besides other projects, worked on the bridge over the Neris River that was destroyed by the 1672 flood no small engineering novelty in the territory of the Grand Duchy in those times.19 He also worked on the church of the Pažaislis Comaldolese monastery, funded by Christopher Sigmunt Pac, as well as for some time overseeing the construction work of the St. Peter and Pauls Church, funded by another noble of the Grand Duchy, Michael Casimir Pac.20 The Polish art historian Anna Czyż asserts that he had also taken part in some of the work in the beginning phases of the Trinitarian Church, built by Sapieha.21 Incidentally, an interesting study on this Italian architects activities in Lithuania has recently appeared that illuminates many little-known facts of his creative biography.22 The sculptor-designer Pietro Perti, who came from the Lake Como area in the duchy of Milan, famous for its ornamental arts traditions (particularly the mastery of stucco decoration), decorated Vilniuss St. Peter and Pauls Church,23 in addition to the Vilnius Cathedrals St. Casimir chapel and the Sluszko Palace, as well as being associated with the decorative work at the Sapieha Palace. It is also known that he carried out the sculptural work in the Jesuit church in the city of Grodno, which was financed by the Sapieha family. So it can be justifiably claimed that the Italian sculptor Pietro Perti, who over time became a Vilniutian, left particularly valuable traces in Lithuanias baroque culture.

Current view of Sapieha Palace.

The detail of the main façade of Sapieha Palace.

Sapieha Palace.

Gates from the park to the palace.

The complex of Sapieha Palace with gates.

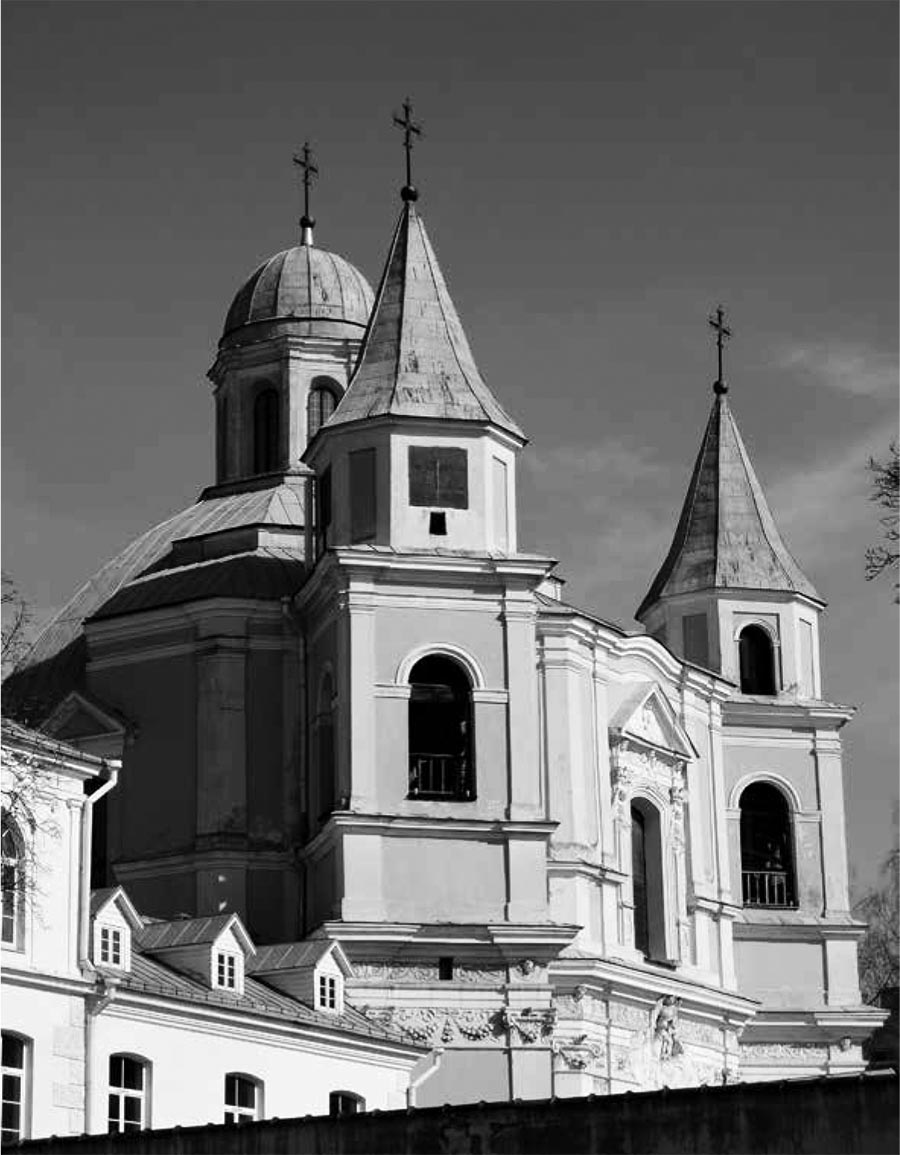

Trinitarian Church in Antakalnis.

Vilnius St. Peter and Pauls Church.

Conclusion

The famous inscription that once adorned the Sapieha Palace and announced itself as Antakalnis, the resting spot of the ancient heroes, now rises from the ruins like a giant home, today could be interpreted only as a nostalgic reference to the short period of this locations flourishing. On the other hand, this doesnt mean that reasoning about Antakalnis or the Versailles of Vilnius was only a fiction of romantically-inclined writers. Based on the information made available by todays historical research, it can be asserted that in the second half of the seventeenth century, a unique architectural and natural complex, connected with several families of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy, formed alongside Vilnius in the suburb of Antakalnis. The layout of this complex was made from several independent components that were formed individually, but relied upon and used examples of analogues in Western Europe, so the concept of the Versailles of Vilnius or Antakalnis is neither pure invention nor the product of a romantic imagination. In creating their suburban residences, the magnates of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy really did follow the most famous European examples of the baroque epoch in striving for their own political and cultural aims. The brief time period of the flourishing of this suburbs impressive accumulation of residences was determined by reasons unrelated to their creators or financial supporters ambitions.

Sic transit gloria mundi.

Works Cited

Drėma,

Vladas. Dingęs Vilnius.

Vilnius: Vaga, 1991.

Czyż,

Anna S. Kościół

świętych Piotra i Pawła na Antokolu w Wilnie.Wroclaw,

2008.

Jamski,

Pio tr. Sapiegų rūmų byla dar nepralaimėta, Kultūros barai,

2007, No. 2.

Janonienė,

Rūt a and E. Purl ys. Sapiegų

rūmai Antakalnyje. Vilnius: Nacionalinis muziejus, 2012.

Janonienė,

Rūta. Sapiegų rūmų Antakalnyje architektas Giovanni Battista Frediani:

biografijos bruožai,

Acta Academia Artium Vilnensis, 7778, 2015.

Kłos,

Juljusz. Wilno. Przewodnik

Krajoznawcy. Wilno, 1937.

Łopaciński,

Euzebiusz. Palac Sluszkow, In: Wilno.

Zarząd miejski w Wilnie. Wilno, 1939.

Pilypaitis,

Antanas and A. Ra ulinaitis. Sluškų rūmai Vilniuje, Kultūros barai,

1967, No. 3.

Purlys,

Evaldas. Kas darytina, kad neprarastume Sapiegų rūmų? Kultūros barai,

2006, No. 11, No. 12.

Rogala-Zawadzki,

Tadeusz, Unpublished manuscript. Authors personal archives.

Samalavičius,

Stasys and A. Samalavičius. Vilniaus

šv. Petro ir Povilo bažnyčia. Vilnius: Pilių tyrimo

centras, 1998.

Samalavičius,

Almantas and S. Samalavičius. The Realm of Lithuanian Baroque: SS.

Peter and Paul, Vilnius, Apollo: The

International Art Magazine, July, 1990.

Samalavičius,

Stasys. Vilniaus miesto kultūra ir kasdienybė XVII XVIII amžiuose, Vilnius: Edukologija,

2011.

Sliesoriūnas,

Fe liksas. Sluškų rūmai, Statyba

ir architektūra, 1967, No. 6.

Vorobjovas, Mikalojus. Antakalnio Versalis, Naujoji Lietuva, 1943, No. 170.