Copyright © 2019 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Editor of this issue: Almantas Samalavičius

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS

AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2019 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume

65,

No.2 - Summer 2019

Editor of this issue: Almantas Samalavičius |

Book Review

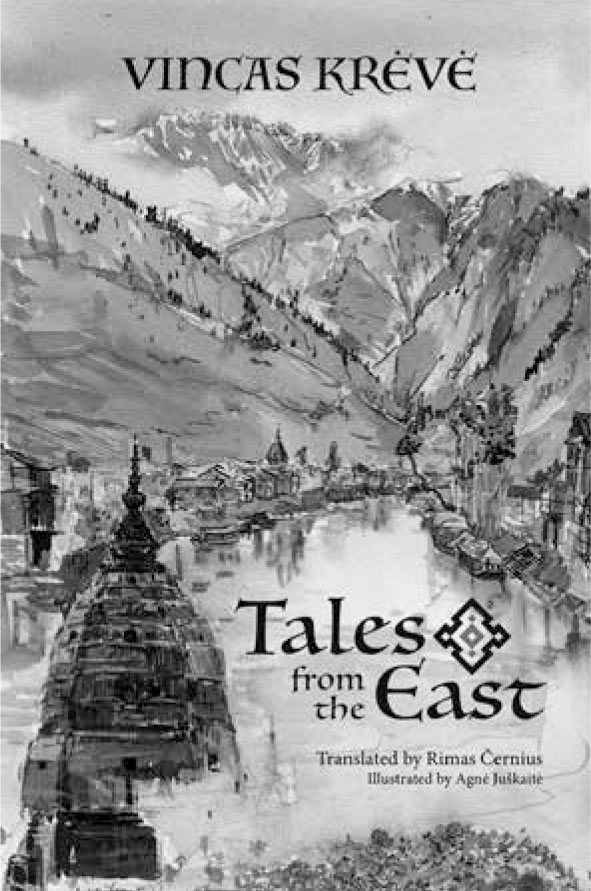

Krėvės Oriental Tales for Grown-Ups

|

Vincas

Krėvė Tales from the East Translated by Rimas Černius. IBJ Book Publishing, 2018. |

Only a handful of people know that Vincas Krėvė-Mickevičius (18821954), the famous Lithuanian writer, wrote his most significant literary works as an émigré. Critics believe that the writers sojourn in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, rendered him one of the most prominent orientalists of the twentieth century in Lithuanian literature. According to writer Mykolas Vaitkus, Krėvės oriental story Pratjekabuda could have been published in any celebrated European literary almanac of that time.1 Unfortunately, during a period in which the West was fascinated with the Orient, no such translation into German or English language appeared, leaving this Lithuanian author and his oriental texts unknown to the world.

Krėvės oriental stories were first translated into English almost one hundred years later. In 2012, Rimas Černius translated Pratjekabuda and a few other short stories on the Orient. Five years later, Tales from the East, collecting five of Krėvės works on oriental themes, was translated by Černius and published in the United States.

Krėvės oriental stories have never been very popular among critics or readers. Upon its first publication in 1913, Pratjekabuda received very mixed and conflicting reviews. Mykolas Vaitkus was fascinated by the story, declaring that it would fit well in the best literary almanac in Europe. Writer and translator Kazys Puida was more reserved. According to him, the story is a philosophical riddle that no reader will be able to crack.2

Although the author calls his oriental texts tales, his stories are far from traditional tales. They convey some of the oldest metaphysical ideas of ancient India and Persia, which Krėvė grounded in the Upanishads, the ancient Sanskrit texts that contain some of the central philosophical concepts and ideas of Hinduism and in Persian mythology.

Pratjekabuda was originally published in the literary and art journal Vaivorykštė (The Rainbow). Krėvė considered the story one of his most significant works on the Orient, and, as Černius notes in his introduction, it reveals the writers philosophy placed on the foundation of ancient India.3 The story is a highly stylized philosophical parable that recounts a mans life, death, and awakening. Regimantas Tamošaitis describes Pratjekabuda as embodying what the author considered the essential ideas of Romanticism, i.e., the power of human spirit, personal freedom, and an individual persons rebellion against the stagnant world order, which, the critic notes, have been too bold and even alien to the earthbound and agrarian Lithuanian culture.4

In an interesting aside, Černius points to another prominent Western writer who wrote on oriental themes: Hermann Hesse. For Černius, Hesses Siddhartha, which came out in 1922, nine years later than Krėvės work, is very similar to Pratjekabuda. The translator suggests that the two tales would make for an interesting comparative study.

The other stories in Krėvės Tales from the East are rooted in Zoroastrianism and Islam. Černius remarks that the story The Vessel in which the Kings Keeps His Best Wine has the flavor of an Arabic morality tale and is perhaps the most accessible of the five tales in the collection. For critic Albertas Zalatorius, the style of The Vessel closely approximates the genre of legend.5 In The Land of Azerstan, Krėvė expresses his affection for the people of Azerbaijan and for the country where he spent ten years of his life. The story Opposing Powers is a Zoroastrian account of the creation of the world, with a traditional plot posing two camps, good and evil. Zalatorius opined that Christian readers will find it a counterpart to the Biblical motif of the Tree of the Knowledge. The story Woman, which is grounded in Islam, is yet another counterpart to the Biblical account in Genesis of the creation of the world.

In addition to its oriental themes, Krėvės Tales from the East stands out for what critic Vincas Maciūnas termed a decorative oriental style.6 Krėvė uses words that fit that genre and makes comparisons and repetitions characteristic of tales and legends. The translator does his best to transmit the authors rich and elevated style.

Here is an excerpt from The Vessel in which the Kings Keeps His Best Wine in which, after deliberating for twenty-one days, his ministers and advisors advise the king:

Noble king and God-given ruler of us all! All of us here assembled have deliberated for a long time, and we have agreed that the most famous and respected man is Arkazar, who rules the neighboring country in the name of his king. He is the most virtuous and wisest of all virtuous and wise men, and there is no other man like him in that respect. His soul is as deep as those bottomless seas which the people call dead seas. His heart is pure and full of love for others, and it is serene like the expanse of the morning sky on a bright day. But, noble king, he cannot become your daughters husband, and you will not be able to call him your son and let him rule the country which you rule, because as much as his soul is noble and pure, so is his physical appearance ugly and repulsive to the eyes; everyone who looks upon him is disgusted.7

* * *

Krėvė, an émigré himself, was highly appreciated by Lithuanian- Americans. On February 27, 1953, Professor Alfred Senn, speaking at the University of Pittsburgh, appraised Krėvė as the most prominent Lithuanian writer of all time, with his rivals for the title being the celebrated Kristijonas Donelaitis and Maironis. Senn dismissed Donelaitis for lacking of originality. According to Senn, Donelaitiss hexameter merely imitated the style prevailing in Western European literature at that time. Though Senn did not offer any criticism of Maironis, he nevertheless judges that Krėvė surpassed him. Even if Krėvė had written only realistic dramas and short stories, he would be worthy of the highest honor and recognition, perhaps even the Nobel Prize, intoned Senn.8

Senns remark about the Nobel Prize was not just rhetorical. In 1952, at the commemoration of Krėvės 70th anniversary, Senn announced to the writer and assembled guests that he had organized a commission to work toward the Nobel Prize for Krėvė. Unfortunately, the professors plans did not bear fruit.

Alfonsas Nyka-Niliūnas, a Lithuanian émigré poet, also attests to Krėvės significant role in Lithuanian literature and among Lithuanian emigrants in the US. Two days after the news about Krėvės death reached the poet, he wrote in his diary: Krėvė died in Philadelphia [the day before]. It is as though the Nemunas, the Vilnius Cathedral, or Šatrija Hill had perished; he was so deeply rooted in my consciousness.9

Krėvės importance in the consciousness of the Lithuanian diaspora and his greatness did not die with the writer. His works have continued to be taught in Lithuanian Saturday schools. New generations of Lithuanian emigrants zealously read his works, especially the historic ones. Therefore it should not come as a surprise that the translator of Krėvės Tales from the East arose from the second Lithuanian emigration wave, also known as the DP generation. Having started translating Krėvės oriental tales as a special project under guidance of Paul Friedrich, Černius completed his work in the Master of Liberal Arts Program at the University of Chicago. It is commendable that the student Černiuss work bloomed into the book.

Černius frequently contributes to the monthly Draugas News and to the newspaper Draugas, both published in Chicago. He is also one of the translators of the book, We Thought Wed Be Back Soon (Aukso žuvys, 2017). I hope that Černius will continue introducing readers of English to Lithuanian literary gems.

Dalia Cidzikaitė