Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 57, No.1 - Spring 2011

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 57, No.1 - Spring 2011 Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas |

Highlights of Lithuanian Textile Art

RASA ANDRIUŠYTĖ-ŽUKIENĖ

Abstract

The author examines the

most important works of textile art in present-

day Lithuania, bringing out the personal contributions of many

individual artists, a number of whom have gained high awards and

recognition at European and world exhibitions. The article expresses

the content of their accomplishments. It also analyzes the Soviet era,

when artists were constrained by ideology in their thinking and

selection

of themes and ideas. Regardless of these circumstances, even

then works of high quality existed, and a unique textile school formed

during this period.

For over ten years now, Lithuanian

professional textiles have

experienced a creative boom and won important awards at international

exhibitions. Respect and admiration often accompany

their presentations at various world exhibitions. They

are characterized as “passionate,”

“inspiring,” “entrancing”

and “fantastic art.” Lithuanian textiles have deep

roots in the

archaic folk culture of domestic life, but they also have made

great strides in the professional art of textile. The formal training

of textile artists started at the Kaunas Art School in 1940.

Several generations of artists matured during the late Soviet

period and after independence was restored in 1990. Although

conditions have been quite different, valuable traditions cherished

by the older generation, relative to a creative application

of folk art, have been taken over by the new one.

A Fragment of Recent History

The fifty years of Soviet occupation brutally restricted creative options for several generations of Lithuanian artists. In the ideologically oppressed country, only openly supportive political or socially neutral decorative art could be created. Textiles were treated as an applied art whose purpose was to aesthetically furnish interior spaces. Rough weaving and monumental compositions dominated exhibitions and public interiors.1 Although Lithuanian textile artists were restricted in terms of ideas, they had a good reputation throughout the Soviet Union. Artists Mina Levitan-Babenskienė, Juozas Balčikonis, and Ramutė Jasudytė were and still are appreciated for their professionalism, subtle colors, their sense for the artistic qualities of fabrics and fibers, and their contribution to the humanization of architectural interiors through their large format works.

The themes imposed on artists in the Soviet era amounted to a ban on thinking. The natural world, motherhood, sports, Lithuanian folklore, the idealized rural world, and the archaic Baltic culture presented with a tinge of a world lost forever were the approved topics.

Changing Motifs

In the 1980s, textiles, like painting and the graphic arts, were marked by reflections of subjective inner states, with signs of traditional modernist culture. In that decade, Lithuanian art underwent a change. Textile artworks created in the 1980s, To Live (1980) by Danutė Kvietkevičiūtė, An Overtaking Express (1980) and Changing Motifs (1982) by Salvinija Giedrimienė, and A Black Cloud above My Valley (1987) by Feliksas Jakubauskas, were clear examples of a changing, more meditative and mysterious art. Painterly weaving is a fascinating aspect of the works by Kvietkevičiūtė and Giedrimienė, while Jakubauskas created a tapestry composition together with the painter Dalia Kasčiūnaitė.

Open Doors

After the fall of the Iron Curtain, the highway of cooperation stretched westward between the former Eastern Bloc and the world in the west and north of Europe.2 In the 1990s, textile’s sudden escape from the grip of habit and tradition was crowned by news of the victory of young textile artist Lina Jonikė’s Chasuble (1996) in the Kyoto Biennial (1997). Jonikė’s creative personality seemed to hide two artists – a textile artist, faithful to the subtleties of weaving, stitching and color, and a conceptualist who used the human body as a medium. This entwining of different arts, which had been unacceptable in Lithuania for decades, as well as an unusual and mysterious visual quality, projected the trajectory of development in textiles and soon became a characteristic feature of Lithuanian textile. The human body, visible and perceived, became the most important object in conceptual works by the younger generation of textile artists.

Independence

At the end of the twentieth century, artists were already creating impressive works of visual art. Stereotyped views concerning the place of textile in the system of the arts (textile as the self-expression of women with a ball of thread) and their attitude towards tradition (Lithuanian folk art as the basis for creation) expanded to include a larger, more global community of artists. The art of Violeta Laužonytė and Laima Oržekauskienė represents two different creative positions, but they are connected by a silent opposition to stereotypes and the expanded possibilities for artistic textiles.

Since the beginning of her creative career in the early 1980s, Laužonytė has firmly chosen the pure values of textile and composition in general. The abstract quality of her compositions conceals the artist’s emotionally perceived reality reduced to optically vibrating linear rhythms in her tapestries. Laužonytė’s style, formed long ago, has changed little. Yet, passing time links certain aspects by its own accord. These are the contexts or parallel creative worlds most often discussed by art historians. Kazė Zimblytė (1933–1999), a Lithuanian abstractionist painter, whose work was banned during the Soviet period, once wrote:

| Bet

kuris gabalas iš mano pasaulio, Pateiktas viešam ar pusiau viešam dėmesiui, Yra mano “paveikslas.”3 |

[Any part of my world, Introduced for public or semi-public attention, Is my “painting.”] |

There are philosophical parallels between the worldviews and the art of Laužonytė and Zimblytė, who, among other things, also created textiles; the quality of reflection links their art.

A feminine attitude imbues the works by Jūratė Petruškevičienė and Danutė Valentaitė. Petruškevičienė’s object, Let Us Tie a Knot for Tradition (2004), reflects a respect for the past, tradition, and values. Valentaitė raises ethical questions in short sentences. For example, in one of her works, she asks a sheep: “How are you, Dolly?” And she answers in a precise, haikustyle, three-line work made from fur with metal spirals. This feminine discourse links our textiles with relevant tendencies in contemporary art: the search for cultural and sexual identity by touching upon taboos of civilized society, such as privacy, inequality, old age or death, and the limits of the public and the private.

A large part of textile art has already become an interdisciplinary phenomenon. In terms of its significance, it has been compared to the new art in Lithuania that emerged in the 1990s with impressive works of object and post-object art created by such artists as Gediminas and Nomeda Urbonas, Eglė Rakauskaitė, Jurga Barilaitė, Artūras Raila, and Svajonė and Paulius Stanikas.

With an Apron or Without

Images of a woman’s world, her passions, dreams and sometimes specific humor, dominate works by Vita Gelūnienė, Almyra Weigel (Bartkevičiūtė), Eglė Ganda Bogdanienė, and Lina Jonikė.

The issue of “the second sex” is hidden in the art of these artists working in different techniques. For Gelūnienė, Weigel, and Bogdanienė, the question of women’s roles in life is fundamental. Gelūnienė is keen to bring it to the foreground in Matrimony (1997). The question of gender relations has acquired a shade of social and aesthetic provocation in Gelūnienė’s textiles. The openness of her works leaves no one indifferent. Naked bodies in the tapestry Happy Days (2005) are realistic, heavy and asymmetrical. People with their hands down look helpless but united. The colors of the tapestry are the bright images of television and the tension radiated by electronic equipment.

Aggressive beauty and the tension of self-identification can be seen in Bogdanienė’s Happiness/less (2006). Bogdanienė uses her own photographs of her face and her body. She conceptualizes the look at herself in her textile works with joy and pain, between laughter and tears.

Jonikė’s work Textile and I (2001) has characteristics of a self-portrait. Yet it is not a “classical” self-portrait. It may seem like the simplest photograph of some body part. The artist uses photographs of her body to emphasise the unpredictability of feminine existence and her varied roles in reality.

The apron as attribute is the discovery of an original technique in the hands of textile artist Almyra Weigel (Bartkevičiūtė). It has become the main reference point in her reflections on the subject of femininity. The artist recreates the sensibility of a woman as seen by the eyes of the Other. She knows that the Other is interested only in the shell, but does not blame him. Elegantly, nonobtrusively and gently, she creates textile novellas about the roles of contemporary women (From the Apron Series: Brides, Hairdressers, and Housewives).

Women and Cars

Sonja Delaunay-Terk, who painted a car in squares at the beginning of the twentieth century. in Paris, could not even imagine that at the beginning of the twenty-first century in Lithuania Severija Inčirauskaitė-Kriaunevičienė would embroider the surfaces of cars with flower patterns (Path Strewn with Roses, 2007). Car parts embroidered in cross-stitches is a textile object conveying multiple meanings. At first sight it seems a bit frivolous. Yet after further consideration, the bouquet of associations and allusions and clashes becomes socially significant.

The visual structure of Monika Žaltauskaitės-Grašienė’s Skin Paintings (2007) was created through digital photography and a digital weaving loom. Although she works with the most up-to-date technology, the artist thinks about the archaic function of fabric: to envelop, to protect, and to warm the body. She says, “A woven fabric is like a skin one cannot live without. It is related to various sensations and feelings.”4 Žaltauskaitė- Grašienė touches on the passage of time with her razor-sharp perception.

Sloughing Her Own Body

These textile artists weave classical tapestries, use digital jacquard and traditional folk weaving techniques and perfect wool felting and embroidery on silk, as well as various techniques of dying and thermal forming of fabrics they have developed and mastered. Various other materials are also used: silicone and glass, metal and plastic, coffee and bread, fur and human hair, and, finally, fruit peels and smoked pig skin. Lithuanian textile is sloughing its own body created from weft and warp, and becoming simply contemporary art. In works by L. Jonikė, Loreta Švaikauskienė, Žydrė Ridulytė, and Jolanta Šmidtienė, the perception of the possibilities of textile materials is so strong that the surfaces of their works, the transparency, structures and textures, become purified and independent elements of their artistic mirage.

Abstract illusory images obey Šmidtienė’s will. Over many years she has perfected her original technique and created an aesthetic construction for her almost impalpable textiles. Constructive knowledge crossed with personal vision in Šmidtienė’s works has become the embodiment of a fantastic mirage.

Instead of Conclusions

Thanks to a lucky accident, there are two textile centers in Lithuania: the Textile Department of the Vilnius Academy of Fine Arts and the Textile Department of the Academy’s branch at the Kaunas Art Institute. Kaunas is an old center of the textile industry. During the Soviet period, nobody doubted that it was in Kaunas where artists had to be trained. However, the hum of the looms of the Soviet industry died one day. In 1996,

Oržekauskienė was appointed the head of the Textile Department of the Kaunas Art Institute. In 1997, the first international biennial Textile97 took place in Kaunas. In 2000, the Textile Artists’ Guild was founded, the only specifically textile art gallery in Lithuania until 2008. “Kaunas is the new meeting place in Europe for textile artists of the world to meet.” These are the words of the leader of the European Textile Network, Beatrijs Sterk.

❖ ❖ ❖

In 1997, at the fifth Kyoto Biennial International Textile Competition, Lina Jonikė won the Excellence Award. In 1997, F. Jakubauskas won the Grand Prize at the Pittsburgh International Tapestry Exhibition. Aušra Kleizaitė received the UNES - CO-Aschberg Fund stipend in 2003–2004. In 2003, Jolanta Šmidtienė won a Special Sliperi Roke Prize at the Mini Textile Exhibition in the USA , and in 2005 she earned the Special Ancor Award from the Embroiderers Guild, UK , and became a member. In 2004, Laima Oržekauskienė received the Outstanding Honorable Award of International Fiber Art at the Shanghai Biennial. At the same biennial, Violeta Laužonytė won Outstanding Honorable Mention. In 2004, Lina Jonikė won a medal of the Polish Artists’ Union in the Eleventh Lodz Triennial. Loreta Švaikauskienė earned a Special Jury Prize and the medal of the Lodz Muzeum at the Twelfth Lodz Triennial in 2007. In 2003 and 2005, Eglė Ganda Bogdanienė won special jury prizes at the Kaunas Textile Biennial. Almyra Weigel (Bartkevičiūtė) won the Merit Prize in the 2007 Riga Textile Triennial. In 2007, Inga Likšaitė won the Grand Prize at the Pfaff Art Embroidery Challenge 07 Exhibition in London and became an Excellence Award winner at the Kaunas Art Biennial Textile 07. In 2008, she also took First Prize at the Art of the Stitch International Exhibition in Birmingham, UK .

Photo from www.lithuanianart.org.

Feliksas Jokubauskas. Blue

Sky, Black Sky.

Wool, silk, synthetic fiber, 130 x 390 cm, 2002.

Photo by

Arūnas Baltėnas

Lina Jonikė. Textile and

I (detail).

Photo image, plastic, embroidery, cotton threads, 2001.

Photo by Rasa

Andriušytė-Žukienė

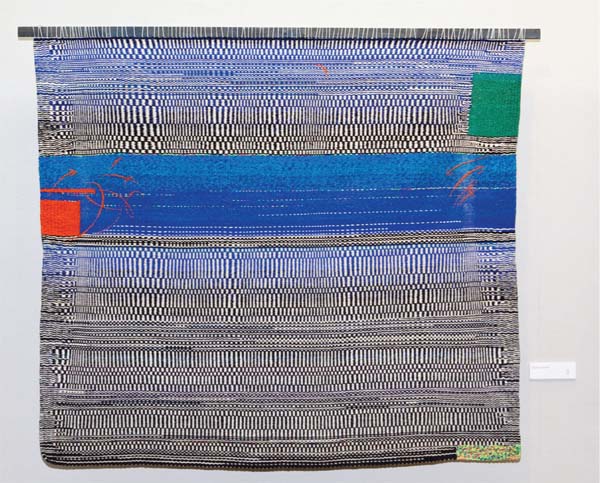

Violeta Laužonytė, Route.

Tapestry.

Weaving and embroidery in wool and synthetics, 155 x 180 cm, 2006.

Lina Jonikė. Textile

and I (detail).

Photo image, plastic, embroidery, cotton thread, 58 x 76 x 2 cm, 2001.

Photo by

Oleg Bovsic

Almyra Bartkevičiūtė-Weigel. Aprons.

Sugar, glue, hair, coffee, salt, spices, 80 x 37 x 20 cm, 2005.

Photo by Rasa

Andriušytė-Žukienė

Severija Inčirauskaitė-Kriaunevičienė. Rose-covered path.

Embroidery, metal, 2007.

Photo by R. Penkauskas

Jolanta Šmidtienė. Radiance.

Spatial embroidery, metal frame, tulle, silk, metallic thread, 40 x 110

x 8 cm, 2007.