Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 57, No.1 - Spring 2011

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 57, No.1 - Spring 2011 Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas |

The Disappearance of Wooden Houses inVilnius and Baltimore

CATHERINE BROWN & RUGILĖ BALKAITĖ

CATHERINE

BROWN is a

2008–2009 U.S. Fulbright Fellow studying

urban planning and development in Vilnius, Lithuania. She earned a

master’s degree in community planning with a certificate in

Historic

Preservation from the University of Maryland at College Park.

RUGILĖ BALKAITĖ is a master’s degree candidate in Cultural

Heritage

Conservation at Vilnius University’s faculty of History.

Balkaitė

lives in Žvėrynas and is completing a scientific practicum at the

Ministry

of Culture.

Wesley MCMAHON is a photographer residing in Baltimore’s

Fell’s

Point neighborhood.

Abstract

The preservation of

historic wooden houses is a challenge for cities

around the world that struggle to adapt obsolete structures for modern

needs and to fund costly restorations. These historic structures

are important components for interpreting the history of our cities.

A comprehensive approach to preservation must include good policies,

predictable incentives and regular programs to encourage strong

valuations of these cultural resources. Preservation policies and

incentives

must compete effectively to support private sector owners

and developers in retaining historic structures and preserving cultural

icons of our past. Comparing the preservation policies and incentives

in Baltimore with those of Vilnius reveals more possibilities for the

preservation of the immovable cultural heritage in both cities.

At the recent height of redevelopment

in the city of Vilnius,

wooden houses on the right bank of the Neris River were

torched to force owners to sell to developers of the city’s

new

downtown, Šnipiškės. While preservation

regulations are no

match for criminal arson, the tragic event highlights an urgent

need for successful protection policies and programs to ensure

that these culturally significant resources are retained for posterity.

There are five historical suburbs in Vilnius where wooden

architecture dating from the late nineteenth and early twentieth

century is still prevalent today. Many wooden homes exist

today due to the lack of development pressure and investment

capital in Soviet times, which resulted in what can be termed

“preservation by neglect,” where homes and

districts did not

undergo extensive changes. While new independence-era city

development has resulted in many positive developments, it is

putting pressure on these vernacular structures, which are vanishing

on a large scale, not only as a result of arson and neglect,

but also as prescribed by adopted plans for city redevelopment.

How and why it is important to preserve this kind of immovable

cultural heritage can be explored by looking at the most

unique district of wooden houses in the city of Vilnius:

Žvėrynas.

In contrast to the number of wooden homes still in existence in Žvėrynas, wooden houses in Baltimore are now an endangered cultural resource. Wooden row houses were once a majority in the city landscape, a testament to the success of the shipping industry, which brought many families to settle in the east Baltimore neighborhood of Fell’s Point. With the threat of fires in the late eighteenth century, many of the hundreds of original wooden row houses in Baltimore were covered in brick. Changes in city building codes prevented the construction of new wood frame homes in favor of masonry structures, and many homes were faced in brick to reduce insurance costs.1 Today, the biggest threats to the preservation of Baltimore’s wooden houses are weather conditions, like flood, rain, snow or wind, followed by termites and fires.2

Wooden houses in both Vilnius and Baltimore face similar challenges to long-term preservation. Small floor plans don’t meet the needs of modern families. Maintenance is cost prohibitive in comparison to more energy efficient homes. In addition, new construction threatens to replace wooden houses. Baltimore City Planner Eddie Leon notes that making an “eighteenth- century living [space] work with twenty-first century necessities” is problematic when considering electrical, plumbing, and handicap access requirements, energy efficiency, HVAC (heating, ventilation and air conditioning), and even furnishings.3 In both cities, adapting historic wooden houses is a challenge, and maintenance can be cost prohibitive, which in many cases leads to neglect. Through a comparison of their histories and regulatory policies, the effectiveness of tools and programs in each city can be highlighted and recommendations made for how wooden houses can be protected and preserved.

Žvėrynas, Vilnius

The Žvėrynas neighborhood has remained an example of the particular lifestyle of Vilnius country dwellers and a recreational area for the highest social classes, offering relaxing getaways from the city amidst a harmonious intersection of people, architecture and nature.4 Žvėrynas is isolated by the Neris River, which bends around the southern edge of the neighborhood and has remained intact as a natural boundary since the beginning of the nineteenth century. At first, the land belonged to the Radziwill family, who used the area for recreational hunting. Private ownership was later passed to the Wittgenstein family in 1825. Prince Wittgenstein organized hunting excursions for noblemen and built the guesthouse known as The Residence. At that time, it was the only structure in the western part of Žvėrynas along the sharp bank of the river, and the southern part remained overgrown with forests.5 In 1901, the land was incorporated into the city, and in the next year, streets were laid out on a grid plan. The Wittgensteins then sold Žvėrynas to the businessman Vasilij Martinson, who in turn subdivided the land and sold individual tracts to city residents. Similar to other suburbs, beautiful, cozy wooden cottages were constructed and the district quickly became an exclusive leisure and residential district.6

|

| Poškos St. 61 Photo www.bernardinai.lt |

Along with their history as a rural area absorbed by the city, the most valuable part of these wood houses is their specific architectural features. In the nineteenth century, builders adorned these country and summer homes with traditional crosscut ornamentation or cut-out patterns, also known as gingerbread, on window hood moldings, cornices, gables and porch features. This method of detailing wood buildings is also characteristic of traditional Russian architecture of that time.7

After World War I, Poland annexed Vilnius, and accordingly, a specific Polish style influenced architecture in Vilnius. Some small manor houses patterned after those from the Polish city of Zakopane remain from this period as examples of the Polish cultural traditions, found in Lithuania only in the Vilnius region.8 Typical buildings reflecting these Polish traditions have hipped roofs and strict symmetrical facades; their main entrance is emboldened with columns and pediments, and accented in the Zakopane Style with a daisy pattern decoration. 9 There are also some influences from Art Nouveau and the Swiss Style, borrowed from the wooden mountain dwellings called chalets. Characteristic of chalet structure, the walls were not built from notched logs, but with framing beams faced with horizontal boards. This structure provided not only an innovative, simple and inexpensive method of construction, but also a new aesthetic: light, open spaces with colorful verandas, loggias, and balconies. Houses also featured double hipped roofs, dentils, gingerbread and numerous trim and crosscut ornaments specific to the Swiss Style.10

|

| Zakopane-style house Photo by R. Balkaitė |

The wooden houses of Žvėrynas offer significant architectural diversity; the surviving buildings dating from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were influenced by the changing political climate. Their locations also reveal their varied historic uses, where some houses were built closer to natural areas like forests or fields as hunting lodges, while others were situated to fulfill their manorial ambitions. Properties and their structures ranged from the simple to the luxurious, from the summer homes of rich and noble officials to the cottages of peasants in adjacent villages. Therefore, the historical suburb of Žvėrynas accurately reflects the varied cultural and socioeconomic identities of the Vilnius countryside.

Despite the diversity, uniqueness and global historic significance of the wooden architecture of Žvėrynas, this heritage is still disappearing. The successful preservation of these structures faces many threats:

❖ First and foremost, we are now living in a society with the fundamental notion that “time (and space) is money.” Nerijus Milerius, a well-known Lithuanian philosopher, recalls that radical, rough additions to buildings or even minimal expansions in floor area, though seemingly insignificant, substantially raised property values, which are increasingly important in the new free-market economy.11 Most owners seek to modify and enlarge the residential area of the existing house to increase its capacity. The destruction of wooden architectural heritage was exacerbated by the invasion of capital during the recent construction boom, when owners strategically fought for financially attractive locations while negatively impacting the integrity of surrounding historic buildings and landscapes.

❖ In the district of Žvėrynas after World War II , many low-income people settled in wooden buildings because at that time they lacked modern comforts and, therefore, provided the cheapest housing, which is still the case. Nowadays most owners of wooden buildings do not have sufficient financial resources to maintain their homes, which are simply left to natural loss, also known as “demolition by neglect.” On the other hand, this means they haven’t been extensively altered, which might be thought of as preservation by neglect as well.

❖ There are, however, a few advocates who want to move into and save wooden houses by implementing only minimal physical changes, but they are discouraged from doing so because they lack faith in the current policies for approving and distributing financial incentives. Most importantly, there is no clear hierarchy of values established for preserving wooden house components. There are no details specified to guide preservation priorities. The approach that ensures the preservation of everything with only limited funds, has demonstrated that over the long-term nothing gets done. Legislation and bureaucratic systems such as those created to coordinate permit approvals fully frustrate the intentions and willingness of even wealthy owners of wood buildings who want to modify and adapt their homes to modern needs. Clear guidelines must be adopted to coax modernization towards a balance between preserving the historic integrity of the building and allowing some flexibility, rather than blindly demanding that every detail be retained. “There is no common financial and legal policy for wooden architectural preservation,” said Albinas Kuncevičius, archaeologist, the former head of the Cultural Heritage Department. Practice shows that even government-approved programs do not have specific allocated funding. Programs draw attention to the problem, but don’t provide the tools to address the issues.12

❖According to Vitas Karčiauskas, the head of the Cultural Heritage Division of the City of Vilnius, the disfigurement of historic properties can be related to a popular misunderstanding about the value of preserving objects of cultural heritage. Buildings should be preserved as they are, with only small changes. That there is no respect for a building’s integrity, is demonstrated by the improvement of living cobditions through a wide range of unqualified and historically insensitive repairs.13

❖The director of the Vilnius Old Town Renewal Agency, Gediminas Rutkauskas, claims that one of the cornerstones of the destruction of wooden houses is the lack of responsibility for private home maintenance and its connection to land ownership. 14 After Lithuanian independence in 1990, the idea that no one has the right to interfere in one’s private affairs was established in the backlash against Soviet-era top-down controls. Today, the right of property ownership is absolute, and each owner determines the maintenance needs and plans for his or her own property. Therefore, the private interests of property owners take precedent over and are often in opposition to retaining publicly recognized cultural values.

❖ Lastly, wooden houses are also influenced, like other structures around the city, by a now ingrained culture of government responsibility for housing maintenance. After over half a century of Soviet rule, these attitudes are difficult to change, especially for residents on fixed incomes or older residents on government assistance.

|

| Lenktoji St. Photo by C. Brown |

Legal Protections and Programs in Žvėrynas

Amidst the controversy over the wooden houses of Žvėrynas, the responsibility for and authority over their architectural significance and value should be assumed by not only art historians and architects, but also cultural heritage professionals. It is important to note that, currently, 108 of the 439 wooden buildings in Žvėrynas are entered on the List of Cultural Property, providing a record of a significant urban ensemble, and the listing of individual buildings is ongoing.15

|

Vytauto St. 63 renovation project, before (above) and after (below), from the Implementation Program for the Wooden Architecture Heritage Strategy. Photo by C. Brown |

|

According to a 1990 survey by the Vilnius Gediminas Technical University and Restoration Institute, more than 80 percent of protected buildings are in particularly poor condition and need urgent repair.16 Now, almost twenty years later, the status of these buildings has not improved, but worsened. To stop the loss of this architectural heritage, the Lithuanian Cultural Heritage Commission17 issued a decision in 2002 on “Lithuanian Wooden Cultural Heritage”18 and adopted a resolution in 2006 to preserve wooden houses.19 That same year, the City of Vilnius published a decision entitled Toward a Program for the Implementation of the Wooden Architecture Heritage Strategy”(2006).20 This program establishes a high priority for the protection of Vilnius wood buildings and their complexes (districts) in order to triage the preservation of a unique heritage. Under this program, in 2008 two wooden buildings, Traidenio St. 35 and Pušų St. 16, were renovated and incorporated into the Immovable Cultural Heritage List. Both houses were restored in cooperation with financial preservation funds from the City of Vilnius and a 50 percent contribution from the owner.21

The foundation of the Program for the Implementation of the Wooden Architecture Heritage Strategy and its mechanism of formation started in 2005, when the first decision to provide financial preservation incentives was amended to the Immovable Cultural Heritage Law.22 In accordance with this amendment, the owner completes restoration, repair, or adaptive reuse in accordance with preservation requirements. The owner may then apply to the Cultural Heritage Department or the local municipality for compensation for the cost of the completed work. In accordance with legal requirements, all work must meet official standards (estimates, projects, planning conditions), although the official knows that in reality work is completed by “economic means,” the cheapest bid.23 Also, because rehab work was partially paid for with public money from the city budget, the owners are required to sign a Security Agreement to give the public access to view the completed work. Consequently, owners who don’t want to give public or tourist access to their private space cannot apply for compensation. Finally, since the Lithuanian government has an evolving financial profile, guarantees for the effective functioning of the compensation program are not created through tax incentives, but through the availability of government funding. Therefore, there is no guarantee that projects fulfilling program requirements will be truly compensated. The program, through flaws in its design, seeks to reduce government compensation rather than create a policy to encourage restoration of historic wooden houses. There is no coherent legislative framework for the preservation of wooden houses in Žvėrynas on a comprehensive scale, only isolated attempts not adequately promoted by the financial sector or state policy. With an increasingly grim outlook for success in future preservation and a dwindling number of existing wooden houses, it is necessary for preservationists and government agencies to adopt new solutions, using targeted methods and proven ideas from other cities, like Baltimore.

Fell’s Point, Baltimore

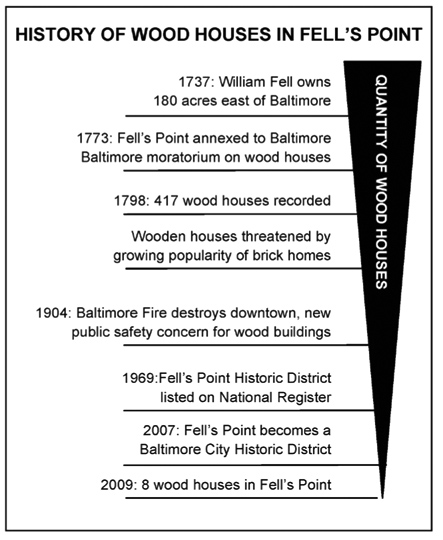

Wooden houses in Baltimore’s Fell’s Point neighborhood are significantly older than those in Žvėrynas and much fewer in number. Baltimore, an American port on the Chesapeake Bay, was established in 1729 and had expanded eastward by 1737 to where William Fell owned over 180 acres of land.24 The Fell lots were annexed to Baltimore in 1773, creating what is known today as the Fell’s Point Neighborhood.25 This historic neighborhood benefits from impressive waterfront views and a prosperous maritime history that has attracted many residents over many years.

|

| 713 Ann Street in

Baltimore. Formstone faced homes flank wood clad

house. Photo by W. McMahon |

Today, the Fell’s Point street grid, first laid out in the eighteenth century, remains intact. The original houses range from one and a half to three and a half stories, although most were two and a half-story residences constructed for seamen, ship’s carpenters, and sail-makers. The larger three and a half-story dwellings housed more prosperous shipyard owners, merchants, and sea captains. The earliest houses in the area featured wide, beaded clapboards.26 As the area prospered from expanding commerce and industry, houses in the neighborhood were renovated and faced in brick and the gambrel roof was often lifted to create a full second or third story.27 These original mid-eighteenth-century wooden houses were the most modest homes in the city. Typical wood homes were twelve to fourteen feet wide, one room deep and only two bays wide, usually with one dormer in the roof, but some wooden dwellings were somewhat larger, with taller gambrel roofs and three or four bays. Most of the wooden homes in existence today in Baltimore are found in Fell’s Point.

This style of narrow townhouse was common in Philadelphia and London, cities that greatly influenced the design and materials of vernacular buildings in the Baltimore area. In 1798, the tax assessor’s records listed 626 houses in Fell’s Point, 67 percent of which were wooden. Today, there are only eight clapboard examples remaining, plus a few that have been refaced in brick, stucco, formstone or vinyl siding. 28 Reacting to the devastating 1904 fire that caused mass destruction, Baltimore adopted building standards that included fireproof materials and mechanisms. Building codes helped change the cityscape from mostly wood to brick housing. The largest concentration of surviving wooden houses in the city is located in Fell’s Point because the new city codes were applied late to this neighborhood.29

Fell’s Point Preservation Regulations

The preservation of wooden houses in Fell’s Point is important not only for aesthetic reasons, but to preserve an understanding of how eighteenth-century shipping industry workers lived. With only a few wooden dwellings known to remain in Fell’s Point, it is valuable to look at the policies, designations, regulations, and programs that protect and promote these architectural and cultural resources.

The national preservation program as it exists today in the United States began with the adoption of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) in 1966, which established a partnership between the federal preservation agency, the National Park Service, and State Historic Preservation Offices (SHPOs). In addition, NHPA created the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, a committee appointed by the President to review federal agency decisions and their impacts on historic properties, and to comment on Section 106 review of federally funded projects.30 SHPOs carry out federal historic preservation programs and review nominations to the National Register of Historic Places and National Landmarks. They also maintain data on historic properties not yet listed on the National Register and consult with federal agencies during Section 106 review. The State also manages programs whereby a conservation easement that runs with the property, not the owner, restricts alteration of the structure for its life, by requiring review and approval by the SHPO. Easement agreements are often executed by the State and the landowner when State grants are awarded for a specific preservation project, but can also be executed as a gift to the state. There are also Certified Local Governments (CLG s) established at the municipal level to carry out the national preservation program with financial support from federal agencies. At each level of governance, preservation tax credits encourage the rehabilitation of National Register listed or eligible properties and compensate owners for the additional costs of maintaining the historic integrity of their structures. The National Register of Historic Places (NR) is a federal list authorized by the NH PA to create an inventory of significant historic sites across the country and it serves as a litmus test for projects participating in tax credit programs. Work must not be completed before starting the tax credit application process so the SHPOs can comment, before changes are made, on renovation plans prioritizing the preservation of features contributing to the building’s historic integrity.

While there are few individual designations for wooden houses in Fell’s Point, it is a national, state and local historic district that has over 161 buildings on the National Register.31 The seventy-six-acre historic district is significant as an eighteenthcentury planned residential neighborhood, featuring most of its original town plan, and as a prosperous shipping community, famous for its War of 1812 clipper ships that fended off the British.32 The Fell’s Point National Register Historic District, established in 1969, is a designation that does not impose restrictions on any properties. It does not prevent individual property owners from altering or even demolishing their buildings, and normal city building codes and local housing standards still apply. The National Register Historic District was established to protect Fell’s Point from the planned construction of a new highway that would have bisected the historic neighborhood. Because a federal transportation agency was implementing the highway project, Section 106 review was initiated. This review is required under the NH PA to evaluate the impact of federal undertakings on significant cultural resources and to take steps to avoid, reduce or mitigate any adverse effects. The proposed freeway was found to have adverse effects on the historic integrity of the neighborhood and the project was terminated.

Owning a structure contributing to the National Register Historic District allows the property owner to apply for federal rehabilitation tax credits. These credits are issued for approved historic rehabilitations to offset the additional costs associated with preservation work and encourage historic renovations.33 The federal program offers a tax credit equal to 20 percent of the total cost of rehabilitating income-producing properties. It does not require full restoration, but allows flexibility within the scope of work as long as the historic integrity of the building is maintained.34 The National Park Service has established a clear set of guidelines for the preservation, rehabilitation, restoration, and reconstruction of historic properties known as the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties, which are administered through tax credit programs at all levels of government.35 The State of Maryland additionally offers a 20 percent tax credit for qualifying capital costs of the rehabilitation of owner-occupied residential or income- producing properties. To encourage large scale projects, the rehabilitation costs for owner-occupied residences must exceed $5,000 in a twenty-four-month period.36

|

| Chart by C. Brown |

In December 2007, Fell’s Point became a Baltimore City Historic District, a designation that provides increased protection from inappropriate development and demolition. The most protection a building can have is a local landmarks listing or historic district designation.The City of Baltimore requires that construction permit requests be reviewed by the Commission for Architectural and Historic Preservation, which holds public hearings to determine if a notice to proceed can be issued.37To further encourage restoration and rehabilitation of historic properties, Baltimore offers a Property Tax Credit for Historic Restorations and Rehabilitations to Baltimore City Landmarks, properties eligible or listed on the National Register, and structures contributing to either a Baltimore City or National Register Historic District when work completed costs more than 25 percent of the property’s value. The Baltimore City preservation tax credit is distributed over ten years and is transferable to a new owner for the life of the credit. It applies to all renovations, interior and exterior. The credit is the most comprehensive and generous in the nation, with 100 percent applied to construction costs totaling less than $3.5 million. For construction costs in excess of $3.5 million, 80 percent of tax credits are distributed in the first five taxable years and the percentage rate declines by ten percentage points in each of the remaining five years. The City is able to administer the credit based on the increased taxes gained from a higher property value after rehabilitation. 38

Significant to increasing the success of preservation efforts, the city’s comprehensive approach includes educational and cultural programs to reinforce the significance of historic resources for locals and tourists. Adopted by the State legislature in 1996, the Baltimore City Heritage Area promotes heritage tourism, preserves historic resources, creates business opportunities, and revitalizes neighborhoods, as well as manages collaborative efforts among numerous local heritage preservation organizations. 39 In March 2009, President Obama signed the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009, designating the Baltimore City Heritage Area as a National Heritage Area. The national designation provides access to up to $10 million in federal funding over fifteen years to develop education programs and exhibits and to protect and restore Baltimore’s historic sites.40 Although this program does not directly ensure the preservation of wood houses in Fell’s Point, it does promote the significance of the shipping neighborhood in general. Special attention given to the Fell’s Point neighborhood, such as new pedestrian way signage, historical society neighborhood tours, and partnerships with local museums, indirectly promotes preserving its historic wooden houses. In addition, there are numerous preservation advocacy groups at national, state, and local levels, such as the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Preservation Maryland, and Baltimore Heritage, which provide education, advocacy, and resources to preserve historic places.

In reviewing the regulations of the various tiers of historic designations and regulations, it appears that there are clear protections working in Fell’s Point. Despite this, many original wooden row houses have been lost. These protections and regulations do not necessarily ensure that wooden houses are not lost to neglect. Left at the will of the free market, it is up to the owners and real estate investors to determine the value of these small old houses in a neighborhood with a competitive real estate market. The best protection available is through a local landmarks listing, but you can see from the example set by the Wolfe Street homes, listed in 1976, how this approach may save the building from demolition, but is wholly inadequate for preventing neglect. The historic wood dwellings in Fell’s Point are obsolete by modern housing standards, but are a valuable part of the maritime history of the city. At last resort, when preservation in situ has failed, these structures will at least be well documented by the photos and detailed descriptions included in the National Register listings and state inventories.

|

| 600 block of Wolfe Street. The Preservation Society recently purchased these early wooden homes for renovation into a museum and academic research site. Photo by W. McMahon |

Recommendations

Reflecting on the significance of historic wooden houses and the effectiveness of preservation policies in both Fell’s Point and Žvėrynas, the following recommendations are offered to better protect, preserve and restore these threatened cultural resources:

❖ The public must recognize the importance of preserving early wooden houses and take ownership for retaining these cultural resources. In a bottom up approach, outreach to the community could create more support for preservation. It is, after all, in the interest of the public good to maintain these significant historic artifacts to better interpret our local histories. Along with installing signs on site to identify and interpret buildings and their significance, historic tours should be encouraged to reinforce the significance of these dwellings.

❖ The local preservation authorities must identify a hierarchy of priorities for the preservation of a structure, items of the house from most to least significant, as well as a priority list of the most important structures to save. For limited municipal budgets, the latter is important to best utilize what in many cases is not enough funding to cover everything.

❖ In Vilnius, laws must be revised to eliminate the public access requirement to qualify for city financial subsidies, following the Baltimore example, where financial incentives for preservation do not mandate public access to private homes.

❖ In both Fell’s Point and Žvėrynas, the historic grid street plan, at the very least, must be maintained along with the forms of lot coverage and building setbacks, organizations of space that create the specific character of each neighborhood.

❖Historic preservation is more costly; therefore, if the government mandates specific controls on building repairs and restoration work, the additional expenses above what a regular renovation project might require should be compensated. In Žvėrynas, it is clear that compensation after the completion of work does not successfully encourage restoration. The tax incentive programs available in Fell’s Point are more successful, and the easier distribution of compensation instills more confidence in owners to pay high costs up front. These programs, however, have not produced outstanding results in either neighborhood, and local governments must continually revisit potential financing techniques.

The preservation of historic properties can only be as successful as the regulatory tools enacted to protect them from alteration, deterioration, or demolition, and the systems in place to enforce those policies. Community interest must be fostered to engage the public to preserve its cultural history. It is in the public interest to preserve immovable cultural resources, and it is the duty of the government to promote their importance and significance through educational policies and programs. With the right combination of protections, programs, and financial tools, cultural heritage objects can be maintained for the enjoyment of future generations.

WORKS CITED

“Article 6: Historical and Architectural Preservation.” Baltimore City 2009. Online: http://cityservices.baltimorecity.gov/charterandcodes/ Code/Art%2006%20-%20HistPres.pdf

Baliulytė, Indrė and Aušrelė Racevičienė, “Vilniaus miesto Žvėryno rajono istoriniai tyrimai” (Historical research of the Žvėrynas district in the city of Vilnius), 1991 m., VAA (Vilnius County Archives). F 1019, Apyrašas 11, Byla 7791.

“Baltimore Heritage Area Designated as a National Heritage Area.” City of Baltimore – Heritage Area. Online: http://www.baltimorecity. gov/OfficeoftheMayor/MayoralOffices/BaltimoreNationalHeritageArea/ NewsandEvents/tabid/233/articleType/ ArticleView/articleId/16/Baltimore_Heritage_Area_Designated_ as_a_National_Heritage_Area.aspx.

“Baltimore City Heritage Area.” Maryland Historical Trust. Online: http://mht.maryland.gov/heritageareas_baltimore.html.

Belfoure, Charles and Mary Ellen Hayward. The Baltimore Rowhouse, New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001.

“Fell’s Point Neighborhood.” Live Baltimore. Online: www.livebaltimore. com/neighborhoods/list/Fellspoint/

“Historic Districts in Baltimore City.” Baltimore City Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation. Online: http://www. baltimorecity.gov/Government/BoardsandCommissions/HistoricalArchitecturalPreservation/ HistoricDistricts/MapsofHistoricDistricts/ FellsPoint.aspx

“Historic Restoration and Rehabilitation Tax Credit.” Baltimore City Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation. Online: http://www.baltimorecity.gov/Government/BoardsandCommissions/ HistoricalArchitecturalPreservation/TaxIncentives. aspx.

Laučkaitė, Laima. “Užmirštas medinis Vilnius (Forgotten wood63 en Vilnius).” Accessed May 28, 2009. http://www.culture. lt/7md/?leid_id=727

Lietuvos Respublikos nekilnojamojo kultūros paveldo apsaugos įstatymo (Žin., 1995, Nr. 3-37; 2004, Nr. 153-5571) 28 straipsnio 3 dalis. Accessed June 20, 2009. http://www.kpc.lt/EasyAdmin/ sys/files/Inventorizavimo%20taisykles.htm.

“Maryland Tax Credits” Maryland Historical Trust. Online: http:// mht.maryland.gov/taxcredits.html.

Medinės architektūros išsaugojimo programa (The Wood Architecture Preservation Program). Accessed June 4, 2009. http://www. vsaa.lt/medine_arch.htm.

“The National Historic Preservation Program.” Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. Online: http://www.achp.gov/nhpp. html.

“National Park Service Incentives.” Online: http://www.nps.gov/history/ hps/tps/tax/incentives/index.htm. “National Register Listings in Maryland.” Fell’s Point National Register Historic District. Online: www.marylandhistoricaltrust.net.

Patterson, Stacy. “Early Wooden Houses in Fell’s Point, Baltimore, MD.” Baltimore Heritage Online: http://www.baltimoreheritage. org/wooden%20house/index.html.

Plašek, M. “Medinė architektūra Vilniaus Žvėryno rajone,” (Wooden architecture in the Žvėrynas district of Vilnius) Medinė architektūra Lietuvoje (Wooden architecture in Lithuania). Vilnius: Vaga, 2002.

Pociūtė, Audronė. “Paveldosaugininkai ir visuomenė – priešingos barikadų pusės?” (Historic preservationists and the public – opposite sides of the barricades?) Accessed May 16, 2009. http:// www.bernardinai.lt/index.php?url=articles/53723.

Rymkevičiūtė, Agnė. “Medinis Vilniaus paveldas: Žvėryno medinės architektūros vertės” (The wooden heritage of Vilnius: the value of Žvėrynas wooden architecture). Accessed June 4, 2009. http:// www.bernardinai.lt/index.php?url=articles/82771.

“The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties.” Online: http://www.nps.gov/history/hps/tps/ standguide/.

Shivers Jr., Frank R. and Mary Ellen Hayward. The Architecture of Baltimore. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004. 64

Surgailis, A. Medinis Vilnius (Wooden Vilnius). Vilnius: Versus Aureus, 2006.

Vanagas J., “Žvėryno rajono urbanistinės raidos istorinė apžvalga,” 1991, VAA (Vilnius County Archives), F 1019, Apyrašas 11, Byla 7791.

Vilniaus miesto tarybos 2006 m. balandžio 26 d. sprendimas Nr. 1-1117. Accessed June 20, 2009. http://www.vilnius.lt/newvilniusweb/ index.php/50/?itemID=508.

Vitanauskienė, Rita. “Vilniuje klesti nelegalios statybos” (Illegal construction is flourishing in Vilnius). Accessed June 20, 2009. http:// www.spec.lt/lt/Vilniuje_klesti_nelegalios_statybos.

Žvėryno studija (A Study of Žvėrynas). Accessed June 16, 2009. http:// www.zverynas.lt/pages/musu-zverynas/zveryno-studija.php.